TRACING THE PATH PODCAST

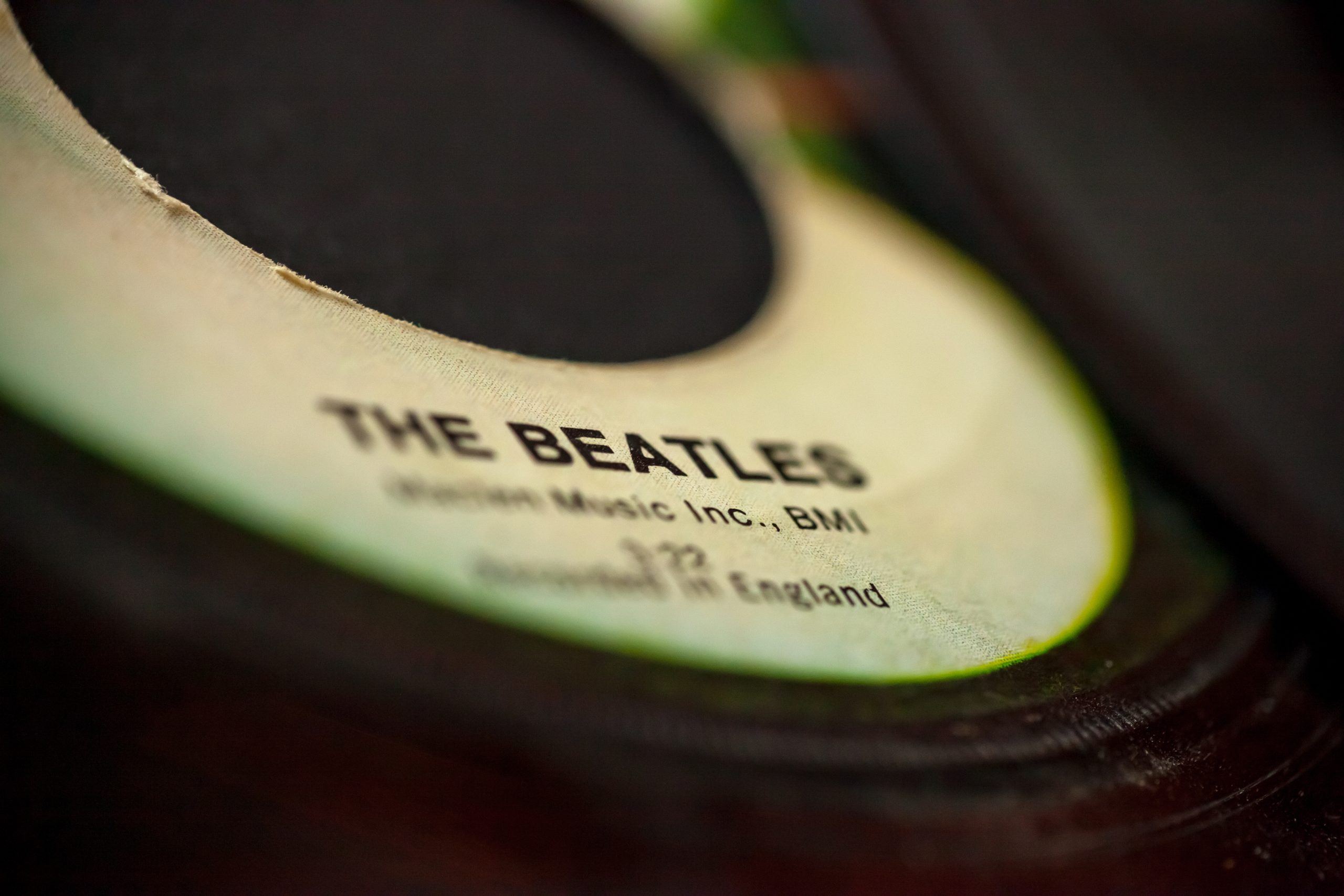

When 26 Million Teens Waited for The Beatles

This episode explores the origins and cultural impact of The Beatles, particularly highlighting how their rise coincided with and helped define a new generation of teenagers in the 1960s. It contrasts the “Greatest Generation’s” resilience through the Great Depression and World War II with the post-war challenges and changing cultural landscape that set the stage for youth rebellion.

The story details how the working-class origins of The Beatles in a war-torn Liverpool, coupled with their intensive musical development in Hamburg, allowed them to challenge societal norms, especially the rigid British class hierarchy, and ultimately revolutionize popular culture both in the UK and America, leading to a new era of music, fashion, and youthful self-expression.

Audio Hour:

If you run an activity group, classroom or “audio book club”, click here for more information on using Tracing The Path.

Throughout the episodes, every tune is somehow related to the topic. In the Twinkies episode, for instance, the discussion of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops Baseball team concludes with “Take Me Out To the Ballgame”.

How many do you recognize? And harder, how many can you name?

When 26 Million Teens Waited for The Beatles

The Big Boom is one theory of how the universe started. They say that was the day something came out of nothing. For 27 million teenagers in 1963 and 1964, the Big Boom of rock and roll is the day their generation started. They had nothing other than being the children of the greatest generation.

And then they had everything.

American Newscaster Tom Brokaw wrote a book to honor his parents. A generation he labeled “The Greatest Generation”. He said they had lived in tough times during the Great Depression and World War II. And for them, the greatest reward for work well done was the job well done.

That generation was truly the working class.

The Great Depression forced them to live without means to find ways to cleverly turn nothing into something. For twenty years across the globe, the greatest generation learned to fix everything themselves.

They created the phrase, “If you want it done well, you have to do it yourself.” and then developed a work ethic that extended to always wanting to be there for anyone in need. And the Great Depression didn’t end in joyous celebration. It ended because this group of people who just spent the last ten years building their country with their hands had to put down the shovels and pick up guns to fight in a war.

For many, the war was on their doorstep and for others it was a 3,000 mile trip.

But no matter who you were or where you lived, the Greatest Generation returned home to their own set of challenges. In Britain, soldiers came home to devastation and a country that was almost bankrupt.

The Rise of Brylcreem

One of the hardest hit cities was Liverpool. It had been both an important factory city and port city. And because of that, the German Luftwaffe had leveled much of the city center with bombs, and what wasn’t bombed, was gutted by fire.

Rebuilding Liverpool wasn’t like much of the rest of the country, however. London was the center of everything British, and, living in a society separated by classes, early money and effort went to London – not Liverpool.

Since the eleventh century and establishment of the British Parliament, the class hierarchy was built into everything, even into Parliament.

Parliament is divided into two houses, the House of Lords and the House of Commons. The House of Lords is just what it sounds like, the upper-class citizenry, like the archbishops of Canterbury and York, bishops, dukes, barons, viscounts, and the Supreme Court justices. And the only way to become part of the House of Lords is to be appointed by one of them, approved by the Prime Minister and formalized by the King.

The House of Commons, however, is made of citizens of the Commonwealth who are elected by the people.

What made rebuilding Liverpool after the war difficult is because its working-class population was already strained. In 1847, when the Great Hunger, sometimes referred to as the potato famine, hit Ireland, 1.5 million people fled. Many went to America and Canada, and others went to England.

Of those, thousands went to Liverpool in hopes of catching a boat to America, but many stayed in and up living in dirty floor basements and in overpopulated tenements. With those destroyed during the war, the people of Liverpool had to house a much greater population while they rebuilding.

Most of the city grew up with rationing, overcrowding, and construction as the norm. Furthermore, many of the independent companies that were nationalized and forced to produce for the war department also had to figure out how to be a company again.

One of those was a company that had started back in 1895 in Manchester halfway between London and Liverpool. A chemist had opened up a shop in the High Street Cozil under the name County Chemical Company. It specialized in lubricants for the fledgling automobile and bicycle industries. While they also had an interest in kitchen cleaning products and things like a lanol oil for hair, they were first nationalized in World War I and were asked to manufacture body armor and the first ever gas bombs.

After World War I, they hit upon something special. It was an emulsion of beeswax and mineral oil, and when applied to hair, would hold the hair in place. It also gave hair a brilliant shine, and so they called it “Brylcreem”.

It hit store shelves in 1928 and was an instant hit and soon it outgrew the manufacturing capabilities of county chemical and was sold to the pharmaceutical giant of the time, Beechem of Beechem’s pills. Beechem had a factory in clock-terre, which were already famous, in the borough of St. Helens, in Liverpool.

During World War II, Beechem was requested to produce pharmaceuticals for the war effort, but was able to continue producing Brylcreem. The soldiers loved the cream, especially the pilots, as it would hold their hair during the most intense battles. In fact, pilots of the Royal Air Force became known as the Brylcreem Boys.

During the Great Depression, Brylcreem sold well in America because they were some of the first to create radio jingles and radios were in every home. But the British government didn’t offer the same radio options.

In fact, only three stations were available to the people, the light program which played light entertainment, the home service which was talk radio, and classical on the BBC Third Program, none of which allowed commercials. Even in the face of shifting time and culture, the British upper class held firm.

When the BBC Third Program was considering being cut, Britain’s elite, like Sir Lawrence Olivier and T.S. Eliot and Albert Camus, formed a group to fight it. But Brylcreem had a secret weapon to keep sales going. The British government themselves.

After the war, the government renewed the need for mandatory military national service. With India and the other Commonwealth nations, the UK needed soldiers. So it remained mandatory that boys 17 to 21 served for 18 months in the military followed by four years in the reserves. And not only that, but Great Britain’s military actions, in places like the Suez Canal, always kept open the need for immediate soldiers.

The traditional slicked-back short hair was not going away soon.

The End of the Greatest Generation

The story was different in America. In fact, everything about the post-war years was different in America. For Brylcreem, the golden age of cinema and the rise of rock and roll created new national icons who wear their hair slicked back and created a popular culture who wanted to look just like that.

James Dean, Elvis, Marlon Brando, James Cagney, Clark Gable, and even the comic book character, Dick Tracy. And while Europe was cleaning up from the war’s devastation, America was experiencing an economic boon that was creating suburbs and prosperity. But the problems of “The Greatest Generation” were not gone.

They were just different.

The defeat of Germany gave rise to the cold war and for the race of one of the two sides to influence the rest of the world. Every gain by the Soviets was a stab in the heart to a veteran.

On October 4, 1957, the Soviets delivered a painful blow. They launched Sputnik, the first satellite into outer space, and not only created a new fear in Americans, but put America second in the space race.

And it was becoming even more clear that Abraham Lincoln’s goal of a free nation had become something different. In 1954, the segregation of schools, a policy created out of ignorance, was found unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. Then, Rosa Parks made a stand to show segregation of buses was also wrong. And then four black students in North Carolina, peacefully staged a sit-in to show segregated lunch counters were also wrong. Fixing race relations was not a problem The Greatest Generation tried to tackle.

And then on the lighter side of life, by 1956, Elvis had become an international phenomenon. Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Jerry Louis, Bill Haley and the coasters were tearing up the charts. Rock and roll radio stations were starting to appear and then it was really the transistor radio that gave the youth the chance to listen.

But even the lighter side of life was about to take a hit, because in 1958 Elvis was drafted into the U.S. Army. And then little Richard flying high on hits like Tooty Fruity and Long Tel-Sally made his decision to leave rock and roll for a life in the ministry.

In 1958, Jerry Lee Lewis was poised to take over as the king of rock and roll while Elvis was in the army. “Great balls of Fire” put him at the top. But on a trip to Japan, it was discovered he had a new 13 year old bride, but he hadn’t yet divorced his first wife.

The public rebelled, his tour was cancelled, and his rock and roll career was over.

But some consider February 3rd, 1959, to be the day the music died. Buddy Holly, Richie Valens and the Big Bopper died in a plane crash in Iowa on their way to a concert. And if that wasn’t enough tragedy in the post-war years, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in 1963.

The lives of the Greatest Generation in America had been defined.

The Great Depression, World War II, dressing like Elvis, the death of rock and roll, and the fall of JFK.

In Great Britain, the Greatest Generation were defined by their societal class, the Great Depression, World War II, and finally, reconstruction left to the working class.

But their tenacity is not the only thing the Greatest Generation gifted the world. The post-war years meant growing families and a baby boom. By 1961 there were already 6.2 million baby boomers who were teenagers. And in America, 21 million boomers were teenagers.

As early as 1954, the British government was seeing their news starting to be loosened. Radio Luxembourg, for example, was broadcasting from across the sea. Its radio waves were making it to the homes of Great Britain, and they were gaining a fan base. In light of this, they immediately decided to grant TV licenses to locations domestically, with the first one being ITV Granada out of Liverpool.

This would mark the first time media was available to the people originating out of some place other than London. For Liverpool it was a chance to share their voice and they knew it. It would be a chance for the people who were considered to be Hicks to show their sophistication and ideology.

The Liverpool accent would be on British TV.

And in another blow to the government’s tight grip on society, Penguin Books released the original edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover by DH Lawrence, and immediately found themselves in a court on obscenity charges.

While Lady Chatterley’s Lover had been printed originally in 1928, it had always been censored until now. The case was brought in front of a jury and was highly public. The press alone caused the sale of three million copies, a book that featured an upper-class woman having a lurid affair with a working-class man.

And the trial itself highlighted the difference between the classes when the prosecutor asked the jury if they would want this book on their coffee table where their servant or wife could read it.

And then in September of 1956, the American movie Rock Around the Clock made its way into theaters across Great Britain. Each one sold out by riotous youth who stood up in their chairs, pushed beyond ticket takers when it was sold out, and in a few cases, caused fights.

The London newspaper the Daily Mirror asked, “Do we want this Shock Rock? Do we want the trouble that comes with rock and roll music?”

The Four Ladsfdfd

Four lads in Liverpool were part of this movement, part of this desire to be heard, not to live within a class, the desire to be part of this worldwide culture shift.

John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr all grew up in the working class districts of Liverpool.

John, Paul and George also grew up knowing they came from Irish families that fled during the Great Hunger, and to some extent that heritage had been considered unwanted. They all grew up with a penchant for music, and in one way or another had played in bands in people’s living rooms, bedrooms, and backyards.

Independently, they all had aspirations of being great musicians in their town. Their expectations of rising above Liverpool were non-existent. Even Ringo, a native of Liverpool, knew the people of London, considered them to be hicks.

Living in the port city did have its advantages, however. The local record store owner, Brian Epstein, tried to get every new record in his shop, and had deals with longshoremen who’d buy albums in America and bring them back.

So the four lads fell in love with rock and roll and listened to Elvis, Chuck Berry, Smokey Robinson, the Ronettes, Buddy Holly, and even Donny Londigan. It took a bit for the four to finally come together as a band, but once they did, they became fast friends.

They played a variety of small venues together, all over Great Britain, and in 1962 they got an opportunity that changed everything. They got themselves a gig in Hamburg, Germany. But the gig wasn’t like anything they’d done prior. It wasn’t like playing a three-hour wedding reception or a two-hour birthday party. They were going to be playing eight-hour days for 102 days to a German club crowd.

Playing covers of “Great Balls of Fire” and “Hound Dog” weren’t going to be enough to keep the job and to keep the audience engaged. So they were forced to try a bit of everything. Jazz, blues, skiffle, rockabilly, rock and roll and classical. And in so doing, they began writing their own songs and took turns singing and playing different roles. They had ample time to play guitar solos, work on their harmonies, and perfect their stage-presence.

Alongside that, they had to become confident in the company of adults, boisterous audience members, and non-English speakers. And they married that with the natural sarcasm, Liver Pudlins, are born with.

According to the book Outliers by Malcolm Gladwell, this was their 10,000-hour rule period. The period of time it takes to become an expert. 10,000 hours together as a band, makes the music tight and flowy. The Hamburg trip wouldn’t have been possible until 1960 when the British government finally eliminated the Military National Service requirement, which also meant the end of short hair.

And for Brylcreem, it meant more hair to slick back. But on John’s 21st birthday, he and Paul went to Paris, where they tried out a new hairstyle, the mop-top, and decided they’d keep it.

Between residencies in Hamburg, the boys who called themselves the Beatles, returned to Liverpool to play gigs at their old haunts. That’s where they really started to garner local fans. Their new tight sound with original songs became the local rage.

Mercy Beat Magazine started writing about them, and then local record store owner Brian Epstein fell in love with their sound and wanted to manage them. Epstein knew they had something special.

While the hair was a bit crazy, he wanted to give them a world-class look so he could pitch them to studios.

That’s when he started wearing suits and ties.

Their Hamburg look which was likely appropriate for eight hour gigs, was already becoming the look of yesterday. Leather jackets, like the one James Dean wore in Rebel Without a Cause and Marlon Brando wore in The Wild One, paired with Indigo-Dye Denim Jeans, just wasn’t hot enough.

In 1962, he secured a contract with EMI and released their first single, “Love Me Do.” That followed by their first TV appearance on ITV Granada and resulted in being number 17 on the charts.

In January of 1963, they released the second single, “Please Please Me,” which shot to number one on every UK chart. The Beatles’ brand of rock and roll was resonating. Their third and fourth singles released in the UK went to number one, which led them to being invited to play the Queen’s annual Royal Variety Show in November.

It would become their watershed moment, and the moment all teenagers in Great Britain had been waiting for their entire lives. Prior to the show, the news was full of talk that the Beatles with Liverpool working-class accents would be performing for the Queen.

And right before the show began, a broadcaster asked the band, “Are you going to lose some of your Liverpool dialect for the Royal Show?” And then in a fashion no adult would ever have responded. Paul said, “No, we don’t all speak like the BBC.” And Lenin repeated the question in sarcastic kings English, followed by an exaggerated Liverpool scouts.

Clearly, the band wasn’t going to change for anyone. And that is exactly what the 6.2 million teenage baby boomers were waiting for. And then the moment that sealed Beatle Mania for good.

Just before their fourth and final number, twist and shout, Lenin came to the microphone in front of the queen and said, “For our last number, I’d like to ask for your help. For the people in the cheap seats, clap your hands, and the rest of you, if you’d just rattle your jewelry.”

This is the moment. It was sarcastic, it was cheeky, it was pointed without being disrespectful, and for every working class bloke in the UK, it was the upper class that was applauding the working men.

The Beatles became national heroes in the eyes of the youth, and when their parents expressed disdain for the riotous long-haired sarcastic rock and rollers, the rebellion by UK teens felt, Ryan Epstein was not there.

Fortune had fallen their way and Brian was ferociously chasing it.

One week prior, the Beatles had completed their first international tour since Hamburg. They had played in Sweden. And upon their return to Heathrow Airport in London, hundreds of Beatles fans had shown up to get a glimpse of them.

Beatlemania

In a complete moment of coincidence, in the airport at the same time, was American TV host Ed Sullivan and his wife. He saw the screaming girls and learned they were waiting for this new band he’d never heard of, the Beatles, and he wanted them on his show. So the first week of November when the Beatles were performing for the Queen, Brian Epstein was in New York, negotiating the Beatles’ appearance on the Ed Sullivan show.

One month later, a DJ in a Washington D.C.’s radio station had obtained a copy of the Beatles’ single “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and started playing it. Bootleg copies made it to other stations and demand grew.

Epstein’s record company partner, Capital Records had no choice but to release it early.

The smooth rock and roll sound all by itself got to number one on the charts and sold one million copies by mid-January, three weeks before their planned Ed Sullivan appearance. And then on February 9th, the Beatles were scheduled to be on the biggest show of the big three networks.

Like British radio, there were only three television stations in the US, so at least one-third of the population would be watching. 73 million Americans tuned in, unlikely all 21.5 million baby boomer teenagers.

Prior to that moment, they’d lived in the shadow of their parents’ heroes, Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry and Buddy Holly. And since the day the music died, nothing had encapsulated their generation until that moment on Sunday night, February 9th.

It left America electrified and speechless at the same time. Dallas Doctor, a musician, a lifelong Beatles fan, and a Beatles historian said this, with as much gravity as words can muster.

“When we saw the Beatles live on Ed Sullivan, we knew we were witnessing a once-in-a-lifetime world-changing event. I was only ten, and I knew it. My grandparents knew it. Every boy in America suddenly wanted to play guitar. I stood in my family’s living room after the show. I have a very clear memory of standing in awe between the heavy curtains in our large picture window. I stood there and looked out into the world outside and realized I was living in a world with the Beatles in it. The world looked different. It felt different. I was ten and I knew it would never be the same and it wasn’t.”

And not just the music, but the fashion, the philosophy, the sensibilities. There was an entirely new and different way of looking at the world and thinking about our shared experience of it. With half the dads of America demanding the TV be turned off in these hippies not be watched, assured America’s teenagers that this was the rebellion they wanted to stand for.

The hair was so different and coming from England, must have been the latest fashion. This was not your parents’ Elvis or James Dean.

For every tear that had been shed since JFK’s death, this was the moment of freedom. This was the moment. It was OK to be happy again. And the music, it was rock and roll, it was pop, it was blues, it was the best of everything.

After that moment, every child in America wanted to learn to play guitar, and guitar sales shot through the roof. Some of those kids who knew in that moment that music was their life. Some of those who saw the Beatles and knew that’s what they wanted, actually did.

Billy Joel was watching and decided being a rock and roll star was his future.

As did Tom Petty, Joel Walsh, Nancy Wilson, Bruce Springsteen, Richie Sambora, Bruce Springsteen, Richie Sambora, Stephen Tyler, Chrissy Hind, Robert Kray, David Crosby, Gene Simmons, Joe Walsh, Rick Nielsen, Stephen Van Zant, and Dallas Doctor.

Some people consider that moment to be the big bang of rock and roll. Others considered it to be the definition of their generation. But one group was likely not prepared for that moment.

Greg Kihn, lead singer of the Greg Kihn band who had a big song “Jeopardy” in the 1980s. Remember that moment. He remembered that the Beatles on Ed Sullivan was on a Sunday night, and that the previous Friday school day was normal.

All the boys had their hair slicked back with Brylcreem, wearing jeans and black jackets. And then on Monday all the kids returned with their hair combed forward all the Brylcreem washed out. All the boys talked about starting a band and all the girls talked about who they liked best.

“Brylcreem never returned to their height of popularity.”

CUTTING ROOM FLOOR

To hear all the stories that hit the cutting room floor, you have to listen to the episode.

ABOUT THE SHOW

Let us tell you the story of the 20th Century, by tracing each event back to the original decisions that shaped it. You’ll quickly find out that everybody and everything is connected. If you thought you understood the 20th Century, you’re in for a treat.

Tracing the Path is inspired by storytellers like Paul Harvey, Charles Kuralt, and Andy Rooney.

INTERCONNECTED EPISODES

|

Who Started the Outer Space Race? Elon Musk isn’t the first person to have his eyes set on Mars. |

|

187 Years Behind Martin Luther Kind’s Dream We all learn about the “I Have a Dream” speech, but few know where it comes from. |

|

Who Killed the American Dream The Day the Music Died is a lot more than a song. It’s the story of a nation in crisis. |

|

How the Transistor and Pirate Radio Created Rock-n-Roll Back to the Future isn’t a “origin of rock-n-roll movie, but then again it really is. Except it doesn’t mention Radio Caroline. |

|

The Fairy Tale of Sixto Rodriguez Ever hear the story of the most famous musician in the world? Neither did he. |

SEE THE BIBLIOGRAPHY

SUBSCRIBE AND LISTEN (FOR FREE!)

RATINGS & REVIEWS

If you enjoy this podcast, please give it a rating and review.Positive ratings and reviews help bring Tracing The Path to the attention of other history lovers who may not be aware of our show.