Who Started The Outer Space Race?

This source highlights the profound and far-reaching influence of H.G. Wells, particularly his science fiction works, on various pivotal moments and figures throughout the 20th century. It traces a remarkable chain of inspiration, revealing how Wells’s imaginative stories, like The War of the Worlds and The World Set Free, directly inspired individuals such as Leo Szilard in the development of nuclear physics, Robert Goddard in the advancement of rocketry and space travel, and Orson Welles in his iconic radio broadcast that revolutionized media. Ultimately, the text demonstrates how Wells’s imaginative foresight contributed to key historical events, from the creation of the atomic bomb and space exploration to the cinematic revolution led by George Lucas’s Star Wars, illustrating the enduring power of speculative fiction to shape reality.

Audio Hour:

If you run an activity group, classroom or “audio book club”, click here for more information on using Tracing The Path.

Throughout the episodes, every tune is somehow related to the topic. In the Twinkies episode, for instance, the discussion of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops Baseball team concludes with “Take Me Out To the Ballgame”.

How many do you recognize? And harder, how many can you name?

On November 9, 2000, Congress passed the National Recording and Preservation Act to preserve the recorded sounds of historical and cultural significance in the National Archives.

Over 550 have been registered, including the following eight:

- Woodrow Wilson. 1923 The War-to-end all Wars Speech

- Theodore Roosevelt, 1933 fireside chats

- Herbert Morrison, 1937 news account of the Hindenburg disaster

- Orson Wells, 1938 recording of War of the Worlds

- Winston Churchill, 1941 Christmas Broadcast

- Neil Armstrong, 1969 message from the Moon

- John Williams, 1977 movie score to Star Wars

- Michael Jackson, 1982 recording of Thriller

All of these historical moments can be connected to one man.

Leonardo da Vinci, in the 15th century, alighted the world with the idea of manned flight. The notion we could fly by balloon or helicopter from one place to another captured the popular imagination.

But it wasn’t until the 19th century that the idea flying into outer space came about. Then it only took about fifty years to go from the pages of a book to the vehicle orbiting the earth, and that miracle can be tied to the ideas of a young kid named Birdie.

Birdie

On the 21st of September 1866, Sarah and Joseph, a housekeeper and professional cricket player, had a son they playfully called Birdie. Birdie grew up curious and adventurous, but at age 9 he suffered a fractured bone in his leg that would keep him bedridden for months.

His dad would bring him books from the library to keep him entertained, and Birdie not only devoured the books, but had an urge to write. His family was always close to poverty, forcing Bertie to work, along with going to school.

But his love of learning did not take a back seat, and he actually won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Science, where he studied biology under TH Huxley. Huxley was Charles Darwin’s best friend and a huge proponent of the natural world. It is from his inspired teachings that Bertie wrote his first book called textbook of biology in 1893.

But the universe had other plans for Bertie.

Perhaps the textbook was the hook, because he wrote his own biology text book and then dozens more books. Nevertheless, his next five books would make him famous beyond celebrity.

Two years after the biology text, he’d publish “The Time Machine” under his given name, H. G. Wells, H. for Herbert, or Birdie. The Time Machine was an instant classic, and it was quickly followed by “The Island of Dr. Moreau” in 1896, “The Invisible Man” in 1897, and “War of the Worlds” in 1898.

His science fiction writing characterized much of his early writing, but after that, his books tackled social ideas, politics, science, and ideology. One of his books, The War in the Air in 1908, was about large blimps and dirigibles crossing the Atlantic to explode in America.

And another, in 1914, “The World Set Free” tells of a bomb that can be dropped from planes to level entire cities.

And another, “The War that will End War” in 1914, was actually paraphrased by Woodrow Wilson and one of his famous speeches.

Many consider Wells a futurist having predicted aircraft tanks space travel, nuclear weapons, dirigibles, satellite television, and to some degree the worldwide web.

He spent much of his life traveling and visiting some of the most important people in the world, like Lenin, Stalin and Churchill and even Presidents Wilson, Harding, Hoover and FDR. He even inspired the Prime Minister of Australia to ban the hunting of penguins.

C.S. Lewis, Aldous Huxley, William Wallace Cook, J.R.R. Tolkien, Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, Philip Morrison, Sherwood Anderson, and Michael Crighton have all claimed H.G. Wells was a huge influence on them. But they were just the beginning.

A young lad in Hungary was becoming a fan of H.G. Wells.

Leo Szilard

Leo was born in 1898 and grew up in Budapest with a civil engineer father who wanted him to become the same. And when he was 18 he was drafted into World War I by the Hungarian government, but they benched him from fighting and sent him to the technical university.

The following year they pulled him back out to fight in the fourth mountain artillery unit, but he caught the Spanish flu and had to return. It wasn’t until later that he learned the entire fourth mountain artillery unit had been annihilated.

The Spanish flu had saved his life.

After the war there was a rising feeling of anti-Jewish sentiment in Hungary, so they moved to Berlin, where he took up physics at the Institute of Technology and attended lectures by Albert Einstein and Max Planck among others.

His works in the field were being noted by all, having invented the electron microscope, linear accelerator, and the cyclotron. And he even worked with Einstein, and developing a new atomic refrigerator.

Then in 1929, Leo came across a book from 1913. It was “The World Set Free” by H. G. Wells. In it, Wells told an amazing tale of a new fangled bomb that could be dropped by planes and would destroy entire cities by the energy from inside the atoms. Its explosions wouldn’t stop.

It was from this book that Leo decided to devote himself to nuclear physics to try and discover a source of power that would enable mankind to travel to other worlds. And then one day, by what seems like an accident, while waiting for a red light, while walking in downtown London, it suddenly occurred to him that if an element split by neutrons, could emit two neutrons while absorbing one, a nuclear chain reaction could be created.

He quickly applied for a patent in 1933 and he got it in 1936.

But he assigned it to the British Admiralty to keep it a secret. He wrote,

“I know what this chain reaction would mean, and I know because I had read H. G. Wells. I did not want this to become public.”

After working a few years and publishing papers on a variety of related topics, many countries began investing more money into nuclear research. So much so, Leo contacted Albert Einstein to tell him of his fears that Germany might be working on a nuclear bomb.

He then drafted a letter that Einstein signed and was sent to FDR telling how about the threat that letter, which is famously known as The Einstein Letter, was actually written by the Hungarian nuclear scientist Leo Szilard.

From that letter, FDR pushed $500 million into the now famous Manhattan Project. That, and a book by H.G. Wells, came the first atomic bomb on August 6, 1945.

Robert Goddard

Across the Atlantic, in Watertown, Massachusetts, Little Robert grew up a country boy, always outside an exploring nature. His father gave him a telescope and microscope to explore even more. He loved to watch birds fly and even enjoyed doing science experiments. He’d experimented with kites and balloons and static electricity, but his life changed forever as well when he was 16, in 1899.

That’s when he read “War of the Worlds” and the heavens opened up in his mind.

From then on, he couldn’t get away from the idea that rockets could one day carry people into outer space. He wondered if the rockets H.G. Wells spoke of could be made in real life. He wondered if he could make some device, which had the possibility of ascending to Mars.

Robert actually cut the branches of his front yard cherry tree so he could see the stars from his room, and actually found himself studying the flight of birds. After reading some aerodynamic papers in the Smithsonian magazine, he started doing his own experiments.

In one case, an experiment involving hanging some objects with ropes, and floating other objects in water, he came into a full understanding of Newton’s third law of motion, and realized how critical that knowledge would be to space travel. He was only 18 years old at the time.

His continued interest in rockets led him to getting his doctorate in physics from Clark University and accepting a research fellowship at Princeton. All throughout his schooling, Robert would write papers on flight, rocketry, and space, submitting them to the scientific American magazine, and he had notebooks filled with this thought-on space travel.

He created a equation after equation, working on getting a rocket into outer space. Publicly, he claimed he wanted to get a camera to fly around the moon, and another to report meteorological data, but he kept quiet about his real goal of developing a vehicle for spaceflight.

The scientific community was still not ready to accept the idea, even as late as 1933.

When he was 30, he wrote HG Wells, from which this is an excerpt.

In 1898, I read your War of the Worlds,” Goddard wrote in a letter to author H. G. Wells. “I was 16 years old [and] it made a deep impression. The spell was complete a year afterward, and I decided that what might conservatively be called ‘high-altitude research’ was the most fascinating problem in existence.”

“The spell did not break, and I took up physics … how many more years I shall be able to work on the problem I do not know; I hope, as long as I live. There can be no thought of finishing, for ‘aiming at the stars,’ both literally and figuratively, is a problem to occupy generations.”

Robert Goddard would introduce the world to the liquid-propelled rocket. He would obtain 214 patents on rocket flight and would lead the world scientists in their own quest for progress. Sadly, he passed away only four days after the first domestic bomb was dropped.

Incidentally, part of the reason FDR pushed the Manhattan Project was because the Germans had developed their own rocket known as the V2 missile and had already fired it at the UK. Many, including Goddard, suspected the Germans stole the plans and ideas for the rocket from him.

However, if it weren’t for the invasion of Pearl Harbor, the U.S. may have never entered the war. While that was the first invasion on our shore, news of invasions was becoming commonplace in the late 30s. And that’s what makes this next story even possible.

Though he did get a rough start as a child, he did excel in school, and he was accepted into Harvard, year after graduation. But young Orson Wells had other ideas. He wanted to act. He got some jobs on his travels in Europe, but it was Chicago that sent him a blaze. It was there that he met Thornton Wilder, Alexander Wolcott, and John Houseman.

And with John Houseman’s help, he started the theater company, the Mercury Theater, and expanded to radio with the Mercury Theater Hour. It was October of 1938 that Orson Wells first heard Abbott and Castellos who was on first routine.

Parking in him was the desire to do something is amazing, something as creative. He remembered hearing a radio broadcast in London a few years prior. It was a fictional radio drama about the London riots, but was told as breaking new snippets, and it created a great panic in London.

He wanted to do that. He wanted to do it the following weekend, Halloween, with something a bit scary.

John Houseman and H. G. Wells’ fan suggested they turn “War of the Worlds” into a radio drama. And with all the talk of Germany invading nearby countries, an invasion story would be perfect.

And so on Halloween night, 1938, Orson Wells introduced the drama at the top of the hour, quickly cut to music, and then told H. G. Wells’ War of the Worlds in breaking new segments.

Except this time, it was a town in New Jersey. And mayhem began. Callers began calling, the police showed up, the news was confused.

Orson Wells became a star.

The power of radio was confirmed, and the people started calling for FTC oversight to make sure the public wasn’t faked out again. Campbell Soup seeing the power of Mercury Theater radio signed on as a sponsor. And H.G. Wells started selling this 40-year-old book again, which is the only thing he thanked Orson Wells for when they met on a radio show years later.

RKO pictures, the largest movie house, offered Orson Wells and John Houseman a two-picture deal. Orson had already been working on an idea. So he and John and a fantastic screenwriter, they knew named Hermann Mankiewicz, wrote and created the screenplay, for many says the greatest movie ever made, Citizen Kane.

Orson and Mankiewicz would actually go on to win an Oscar for that screenplay in 1941.

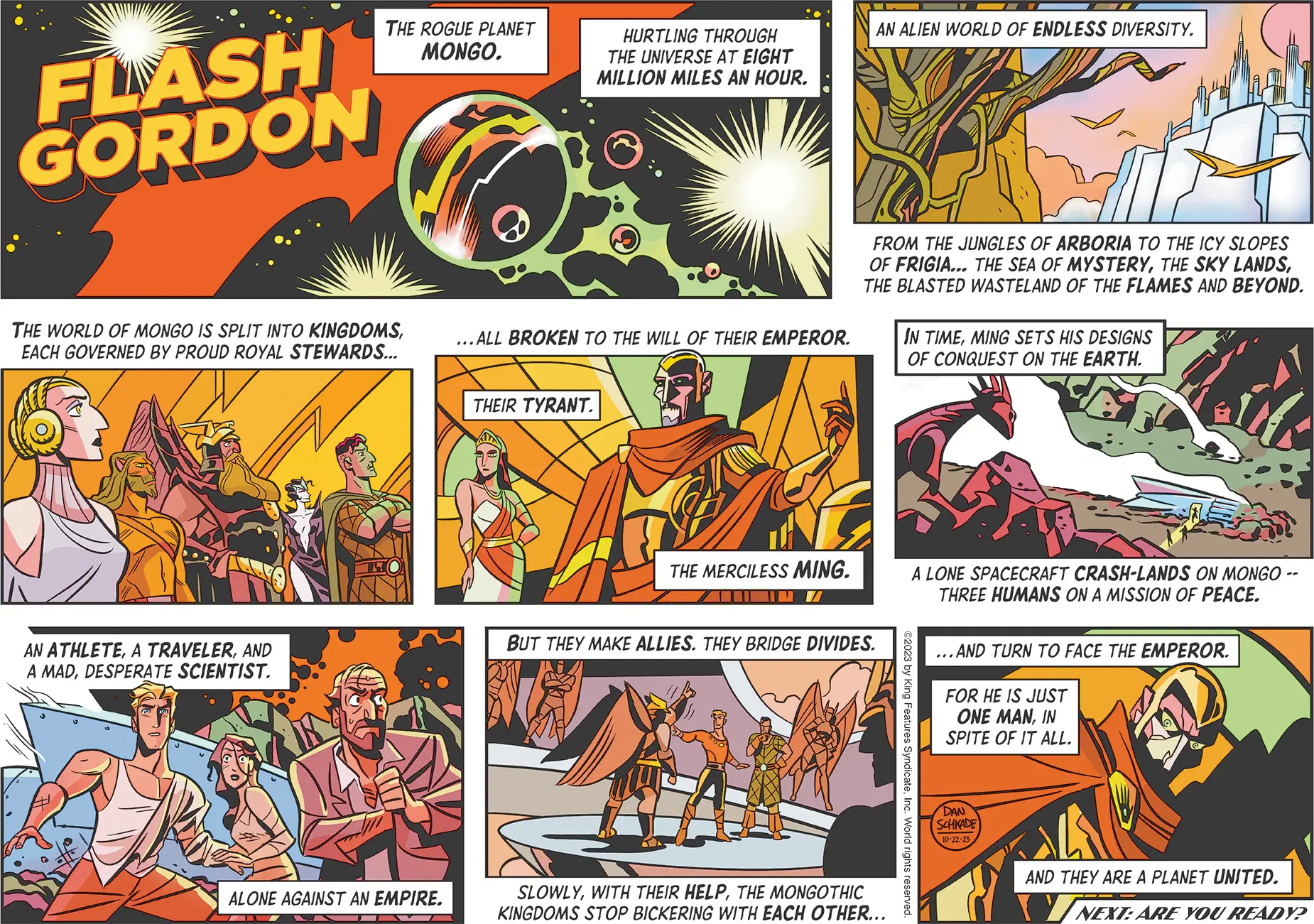

That radio dramatization of HG Wells’ World of the Worlds would inspire a new generation of dreamers. In fact George Lucas, who was born in the forties, grew up reading H.G. Wells’ Jules Verne and Flash Gordon. He too wanted to create something as amazing as these guys, and actually tried to buy the rights to Flash Gordon.

Knowing what Orson Wells did to H.G. Wells’ book, he thought that he might be able to do the same thing for Flash Gordon. But when he tried to buy the rights, they weren’t available.

Because of that, he had to write something original. What he loved about War of the Worlds was H.G. Wells’ use of the familiar to go with the extraordinary. In his story, amazing technological marvel killing machines from the sky were set in everyday believable England.

In this, when he set out to make his movie, he wanted. He wanted there to be a good level of normal. Desert, forest, and swamp scenes to add realism to the fantasy. Since NASA and Neil Armstrong had recently set foot on the moon, and since the Viking 1 and Viking 2 were sent to Mars all using Goddard’s technology, people in space would now be truly believable.

When Star Wars came out in 1977, it reinvigorated the world towards science fiction, as H.G. Wells had done 70 years prior. Nothing like it had ever been made and it quickly became the highest grossing film of all time.

But then in May of 1978, it was gone.

There was no VHS or DVD or streaming or Netflix. It sat in George Lucas, but there really wasn’t a way for people to still consume it, other than licensed novels and merchandise. But 1977 was also the year Frank Mankiewicz became president of the National Public Radio.

Frank is Hermann’s son, the screenwriter who wrote Citizen Kane with Orson Wells. Frank was eager to make his mark on the entertainment industry as did his dad. Though the 1967 public broadcasting act had created NPR for educational programming, he wanted to do more.

One day, in 1981, he got that chance. A long time friend of his fathers, who co-wrote War of the World’s with Orson Wells, was calling. John Houseman was now the chair of the Division of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California. He had a bold idea to share.

They wanted to take the highest-grossing film of all time, Star Wars, and turn it into a radio drama. But they were going to need help because it sounded like such a big project. Frank was on board and got the BBC to help. Their biggest hurdle was going to be the fee required to get access to the script, the music, and the sound f/x.

They hoped, since George Lucas was a USC alum, that he might be on board as well. And then when they asked him, he was delighted to help. He was a huge fan of radio dramas, like War of the Worlds, but was most excited that children who didn’t have money to go to the theater would be able to hear the story for free.

Like all the books that he’d read from the library, George actually agreed to sell the rights to the story, the script, the music, and the sound effects, to USC and NPR for $1. Not only that, but the actors who played Luke Skywalker, C3PO, Lando Calrissian all agreed to be part.

And later that year, the Star Wars radio drama was heard by millions of people. The station got 500,000 letters and phone calls, and the long-term audience growth jumped 40%. Unlike the days of Leonardo da Vinci, today’s children think of space travel as easily as they think of apples.

All children will always know that there’s a manned space station, that there are satellites that can shoot down missiles from outer space and that a helicopter flew on Mars.

On December 20th, 2019, President Trump created the newest branch of the U.S. military, the Space Force.

And in June of 2021, our daughter Grace graduated from Space Force Bootcamp. Our children have come a long way from telescopes and bottle rockets. Leo Szilard, Robert Goddard, George Lucas, and Orson Wells impacted the world in a big way, and they were all influenced by the ideas of one man, H. G. Wells.

And with that, we leave you with this quote by Margaret Mead, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has. You’ve been listening to Tracing The Path with Dan R Morris.

CUTTING ROOM FLOOR

To hear all the stories that hit the cutting room floor, you have to listen to the episode.

ABOUT THE SHOW

Let us tell you the story of the 20th Century, by tracing each event back to the original decisions that shaped it. You’ll quickly find out that everybody and everything is connected. If you thought you understood the 20th Century, you’re in for a treat.

Tracing the Path is inspired by storytellers like Paul Harvey, Charles Kuralt, and Andy Rooney.

INTERCONNECTED EPISODES

|

How a Tennessee Student Overturned the Scopes Trial Verdict Can you believe the 1925 Scopes Trial was undermined by a Tennessee high school senior? |

|

How the Hostess Twinkie Survived Death Twice Did you know the toaster was invented before sliced bread? And Twinkies almost didn’t survive the 80s. |

|

The Official Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon It just so happens Tracing the Path is friends with the creator of the Six Degrees, and he’s only 1 degree away. |

|

The Cropduster, The Military Plot and Lindbergh’s 322 bones The world of Lindbergh is wrapped up into so many things. |

|

The Wizard of Oz’s 30 Year Miracle Beyond every American watching the Wizard Of Oz, this story has ties to Frank Lloyd Wright. |

|

The America of Tarzan and Buck vs Bell When Tarzan and the Supreme Court defined the popular culture |

|

The Surprising Life Story of Paul Harvey Pearl Harbor, Pilot, Chicago and Coca-Cola; The World’s Most Prolific Radio Man |

|

Believe it or Not? A cartoonist saved our national anthem. And not just a cartoonist, an American Military March composer as well. |

|

1848 The Year Halloween Began Have you ever heard the origin of Halloween? |

|

The John Williams Legacy You Knew Nothing About John Williams of Star Wars? of Looney Tunes? of the Boston Pops? of Toto? |

SEE THE BIBLIOGRAPHY

SUBSCRIBE AND LISTEN (FOR FREE!)

RATINGS & REVIEWS

If you enjoy this podcast, please give it a rating and review.Positive ratings and reviews help bring Tracing The Path to the attention of other history lovers who may not be aware of our show.