How the Transistor and Pirate Radio Created Rock n Roll

Audio Hour:

If you run an activity group, classroom or “audio book club”, click here for more information on using Tracing The Path.

Throughout the episodes, every tune is somehow related to the topic. In the Twinkies episode, for instance, the discussion of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops Baseball team concludes with “Take Me Out To the Ballgame”.

How many do you recognize? And harder, how many can you name?

How the Transistor and Pirate Radio Created Rock n Roll

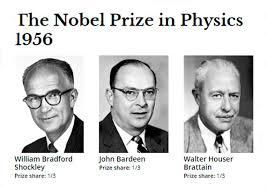

In 1947, three guys, John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, and William Shockley would change the world forever. That’s the day they invented the point-contact transistor. An invention so significant, it would usher in the information age.

Nine years later, in 1956, they would be awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics. One year before their invention made its permanent impact.

Long long ago, back in 1678, the British government recommended no newsletter or pamphlet be permitted in a coffee house until it had been approved by a mayor or an old woman, which brings us to our story.

When Stephen Carwardine opened his first coffee shop in 1926, he didn’t bother with the newsletter or pamphlet rule. Instead, he decided they’d play records on the gramophone to entertain their customers.

At that time, radio and music were very public activities where listening to either was not something you’d do alone. Headphones and a coffee shop would be weird.

For many families in the United States and Europe alike, radio’s in the 1930s took up most of the top of the dresser. They were stained wood boxes with half-inch apertures for tuning. The speakers had a silk-backed fretwork panel standing apart and separate still was the book-sized battery. And finally, there was an accumulator that needed charging once a week.

A radio’s essential purpose was family entertainment. The audience was expected to be a living room gathering, families listening after tea, father in his armchair and mother darning socks. That held the same for coffee houses where live music was being played, or in the case of Stephen Carwardine, records being spun.

But in 1934, the record companies, EMI and DECA, took Carwardine to court. They didn’t object people listening together at a coffee house, but objected to public playing records without royalties. And the courts agreed, Stephen Carwardine would have to play licensed radio, not records.

EMI and DECA then formed the phonographic performance limited, the PPL, to represent artists making sure they got paid when someone dropped the needle on the record. This notion became known as needle time.

The PPL negotiated with the BBC radio as well. They not only wanted to track royalties for artists, but also wanted to make sure the music wasn’t played so often as to cut into album sales.

The Rise of Radio

At this point in human history, radio was really new. Much of the infrastructure didn’t even exist yet. The first multinational conference on radio had just occurred in 1906, and it took the sinking of the Titanic in 1912 before it was clear that there needed to be some international standards.

The Titanic event spurned the second international radio conference, which is where the SOS signal with firmware time disasters was established among other things. And then it wasn’t until 1927 that frequency bands were regulated by use, such as bands for maritime use, bands for fixed use, and bands for amateurs.

And then another five years after that, before the ITU, the International Telecommunications Union, was even formed. And it wouldn’t even be recognized by the UN for another 20 years. Radio was in its infancy.

And while the PPL was focused on needle time and royalties, the ITU had another focus.

Radio waves crossed international borders, which caused conflicts, especially in Europe where countries were so close together. One country’s emergency band could be overridden by another country’s talk show channel. Some sort of regulator needed to be recognized by everyone. Not everybody had the same ideas when it came to regulation, and the ITU didn’t have every country’s cooperation yet.

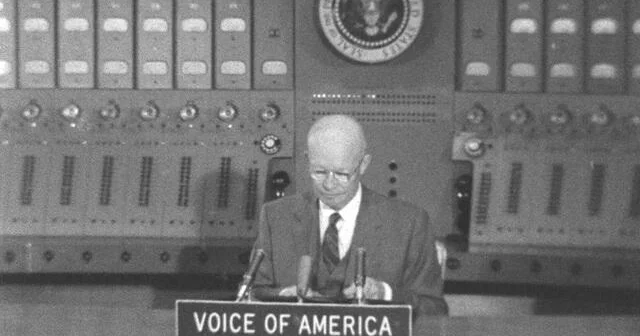

Some countries, like the United States, were broadcasting across country borders on purpose. In 1942, the U.S. established a state-owned radio and TV network called Voice of America. It would be a political propaganda and military tool masked as a good neighbor program. By 1943, the VOA were producing over a thousand programs consisting of news, commentary, and music. And because of World War II, they had 39 transmitters around the world providing service in 40 languages.

Voice of America

Ten years later, the US military trying to abide by the ITU’s broadcasting standards converted an old US Coast Guard cutter and turned it into a broadcast station, then moored it off the coast of Rhodes’ Greece. International waters, not even the ITU could regulate the open ocean.

Fortunately, their good neighbor program would get some help from a music evolution that was starting back in the United States.

Music From America

In the 30s and 40s, music was starting to change. Jazz, Swing and Country were being influenced by African-American sounds and the blues. Rock and roll elements were starting to emerge. Horns, boogie-woogie beats, amplifiers, and shouted lyrics were increasing in use.

Record labels sprung up like Atlantic, Sun, and Chess, eager to find these new artists. The likes of Fats Domino, Sam Phillips and Bill Haley started to make a name for themselves.

In 1951, WWII Armed Forces Radio disc jockey, Alan Freed, got a late-night job at WJW Cleveland, and started playing this new style of music after hearing from a record store owner that his rhythm and blues albums were really getting a lot of interest.

Alan was the first DJ to play this rhythm and blues style music on a large audience station. Even though it was a late night show, it became so popular, tapes of his program began to air New York, New Jersey and other big cities. And then in 1954 and 1955, Chuck Berry’s Maybelline, Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock”, Elvis’s “That’s Alright”, and Carl Perkins’ “Blue Swade Shoes” cemented the movement.

The music evolution was over. Rock and Roll was born.

In November of 1955 in Hill Valley, California, “Earth Angel” was being performed at the local Enchantment Under the Sea High School Dance. That’s where Marty McFly ended up when he went back to the future and played Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode” stunning the audience with his guitar playing.

Standing up to the quiet stunned audience, he said, “I guess you guys aren’t ready for that yet”.

That line is in the movie for two reasons.

- “Johnny Be Good” didn’t actually come out for two years in 1957. And

- . . . .remember those heroes at the beginning of our story who invented the point-contact transistor? Well, it wouldn’t change the lives of America’s high school students for another year.

Things were different in the UK.

In 1952, the magazine New Musical Express started. They were writing about the top pop singles in the UK and had a music chart like Billboard and reported news on all emerging bands. For people to actually listen to the song, however, they had to buy albums from record stores.

UK youth didn’t have access to radio stations that played rock and roll, because BBC Radio was much too conservative for rock and roll. In the mid-1950s, British citizens were offered three stations, the Light Program, which aired light entertainment and light music, the Home Service, which was talk-based, and the BBC Radio 3 program, which largely played classical and opera music. As the culture shifted, tastes in music also shifted.

BBC’s Radio 3 program, which focused on classical, began to lose listenership, and at one point was considered a station to possibly shudder. The cultural elite in England didn’t want that to happen at all. Led by T.S. Eliot, Albert Camus, and Lawrence Olivier, The Third Program Defense Society, formed to protect it.

Even in 1957, it was clear modern radio was not on the horizon.

The Transistor Radio Revolution

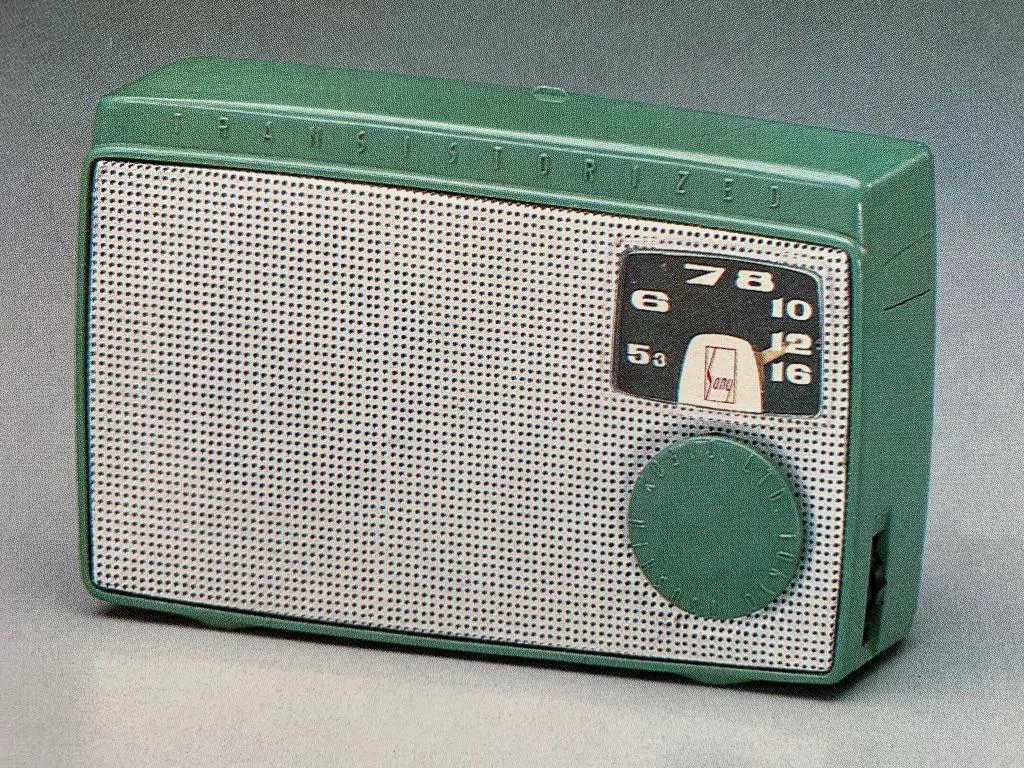

That brings us back to our three heroes and their point-contact transistor. Invented back in 1947, it wasn’t until 1954 though that two companies showed interested in using the technology. Both companies thought the point-contact transistor could be used to make a better radio. They were correct.

Texas Instruments introduced to America to the first-hands-held transistor radio, the TR-1, and Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo KK introduced the TR-55 in Japan. Even though the TR-1 was expensive, hundreds of thousands were sold in the US. The TR-55 was quite a bit cheaper in Japan, and seeing the potential wanted to sell theirs in the US market. However, they didn’t think their company name would do well in the US.

Searching for a new name, they stumbled upon the Latin route “sonos,” meaning “sound,” and decided to enter America under their new name “Sony,” with their TR-55 transistor radio, lowering the price for everyone, and then hundreds of thousands of more radios began to sell.

You probably have a passing memory of transistor radios as small simple devices that had a pop-up antenna and about nothing else. In fact you probably assign no significant historical value to them.

But the transistor radio revolutionized the American culture, let alone the entire world.

Prior to the transistor, you truly would listen to the radio as a family. For most of the younger kids, that meant listening to what their parents listened to. Baseball games, the Metropolitan Opera, News and Classical Music. But whether it was in your pocket, slung on your wrist or in your backpack, the transistors freed everyone to be able to listen to the stations of their choice.

And in so doing, whether in the garage or hiding under their sheets, the demand for music 24 hours a day skyrocketed. While Alan Freed helped meet the demand in the US, or perhaps in Cleveland, the youth in the UK were not given more options. The BBC Light Program played some recorded music, but the PPL limited their needle time to 30 hours per week.

With the explosion of rock and roll over 100 companies applied for a British radio license, the British public was hopeful since the BBC had recently allowed commercial television. But in 1960 they ultimately decided the British public did not want commercial radio.

Sir Harry Pilkington had commissioned a committee to decide the future of British TV and radio. Citing shows like I Love Lucy and American Westerns in the House of Commons, his compatriot, Mr. Kenneth Robbins of St. Pancras, North, said this.

“Look what has happened to commercial television, because it is dependent on advertising. It was forced to aim at the lowest common denominator in popular entertainment, and please the masses. And with that, all 100 commercial radio applications were turned down. The British government did not want to appeal to the masses. With transistor radios and more coming all the time, the demand for modern radio was at an all time high. Ronan O’Rahilly, a music promoter and nightclub owner, was tired of EMI and DECA dictating everything.

Ronan managed a few big artists like Georgie Fame, and his nightclub brought in big names like The Rolling Stones. After shopping his artist’s music to the BBC stations, he decided his only option was to build a station of his own.

He knew about the US Navy ship broadcasting off the coast of Greece and another one, Radio Luxembourg, broadcasting music from international waters outside that country. So he rounded up investors, bought a mast and an extra-man Navy ship and on Easter Day 1964 launched Radio Caroline by broadcasting the Rolling Stone songs “It’s All Over Now” to the British public.

It really wasn’t the British government laws that gave rise to these pirate radio stations. It was a perfect storm. Rock and roll was exciting and enticing. The transistor radio gave everyone a way to consume the music, and the laws couldn’t hold that back.

Pirate Radio

Pirate radio took off and Rock and Roll bands finally found a home in the UK. But it was more than just rock and roll. The DJs had to come up with 2,500 songs to play every week, so all kinds of new music was being heard overseas. By the mid-60s, a dozen stations were floating around the UK, not to mention also in New Zealand and other places in Europe.

The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Dave Clark Five, the Who, Tom Jones, Bob Dylan, the Moody Blues, and hundreds of others owe their success to these rogue entrepreneurs. And they weren’t shy to show their appreciation, either. Beatles George Harrison actually wrote a check to help keep radio Carolina afloat at one point.

And Paul McCartney would record special messages to the fans for broadcast on Radio Caroline, including a regular Christmas broadcast. The Who made an entire album to sound like a pirate radio broadcast, called “The Who Sell Out.” Bob Dylan praised pirate radio in his song “Key West” Philosopher Pirate.

Radio Caroline

The top 20 Hits chart in New Musical Express magazine became a show on Radio Caroline and the standard for the UK. Pirate radio’s first number one hit was Tom Jones’s “It’s Not Unusual.”

And songs with sexual overtones that were never allowed to run on BBC made it to the top 20 charts like The Rolling Stones “Can’t Get No Satisfaction.” Pyro Radio became UK culture, and largely there was nothing the British government or the ITU could do to stop it. Until 1967, when the British government passed the Marine Broadcasting Offences Act, which outlawed anyone in Britain supporting, working for, or advertising on offshore radio stations.

The law did shut-of-the-doors on many pirate radio stations. But then six weeks later, putting a nail in the coffin, the BBC launched Radio 1, a new station based on what pirate radio stations had been doing, including hiring Tony Blackburn and the other pirate radio celebrity DJs. After that the last ship was docked.

In every instance, the existence of offshore radio stations forced nations to break their monopoly on radio broadcasts or create their own. And while it was sad to see pirate radio come to an end, it was an awfully dangerous way to show the world the power of music.

And in the end, many of the pirate radio stations became licensed stations. And many of the celebrity DJs had illustrious creators in BBC Radio and television.

John Bardeen, Walter Batain, and William Shockley, invented the point-contact transistor. The invention of which changed the world. Without the technology behind the transistor, radios, computers, rock and roll amplifiers wouldn’t exist.

There never is one thing that’s responsible for everything. It’s always a culmination of events, a perfect storm per se. In this case, the demand for radio, the transistor radio invention, pirate radio, British regulations, everything coming together at once as it were created the culture of the 1950s and 1960s.

Welcome to Tracing the Path with Dan R Morris.

CUTTING ROOM FLOOR

To hear all the stories that hit the cutting room floor, you have to listen to the episode.

ABOUT THE SHOW

Let us tell you the story of the 20th Century, by tracing each event back to the original decisions that shaped it. You’ll quickly find out that everybody and everything is connected. If you thought you understood the 20th Century, you’re in for a treat.

Tracing the Path is inspired by storytellers like Paul Harvey, Charles Kuralt, and Andy Rooney.

INTERCONNECTED EPISODES

|

When 26 Million Teens Waited for the Beatles The phenomenon that occurred when the Beatles were live on the Ed Sullivan show could have been predicted. . . |

|

Who Killed the American Dream The Day the Music Died is a lot more than a song. It’s the story of a nation in crisis. |

|

James Bond Ghost Armies Ungentlemanly Warfare Ian Fleming was much more than the author of James Bond. |

|

Roald Dahl: The Real Chocolate Spy You probably know about Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Matilda and the Chitty Chitty Bang Bang . . . but you didn’t know this. |

SEE THE BIBLIOGRAPHY

SUBSCRIBE AND LISTEN (FOR FREE!)

RATINGS & REVIEWS

If you enjoy this podcast, please give it a rating and review.Positive ratings and reviews help bring Tracing The Path to the attention of other history lovers who may not be aware of our show.