How Negro League Baseball Solved the Cuban Missile Crisis

Today’s episode explores the deep, intertwined history of baseball in both the United States and Cuba, revealing how the sport became a powerful symbol of national identity and even defiance, especially for Cubans under Spanish rule. The text highlights baseball’s evolution from a casual pastime to an organized sport, detailing its integration across racial lines in both countries, often with Cuban leagues preceding American ones. Ultimately, the source reveals a surprising connection to the Cuban Missile Crisis, where the absence of baseball fields in U.S. spy plane photos of a suspected Soviet installation provided crucial confirmation of its true, non-Cuban nature, thus indirectly preventing a potential global conflict.

Audio Hour:

If you run an activity group, classroom or “audio book club”, click here for more information on using Tracing The Path.

Throughout the episodes, every tune is somehow related to the topic. In the Twinkies episode, for instance, the discussion of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops Baseball team concludes with “Take Me Out To the Ballgame”.

How many do you recognize? And harder, how many can you name?

Baseball. Since the 1880s, baseball has been considered America’s national pastime, but we’re not the only ones. Cuba also adopted the sport as its own, but unlike the United States, for Cuba, it has been a true symbol of national pride.

But few know the story of how baseball prevented World War III.

What you’re about to hear has never been told before.

There’s no real origin of baseball. After all, who would have recorded the first time a child tossed a stone in the air and hit it with a stick?

We do know a British children’s book in 1744 had a poem about it. And we know a baseball craze hit New York City in the 1850s, with journalists calling it the National Pastime. What we don’t know are how many playground games have been played between the two.

We do know that by 1857, the Knickerbocker Club, and the National Association of Baseball Players, made baseball a nationalized centralized and organized sport.

And America’s sugar trade with Cuba led to Americans playing baseball at the dockyards with their Cuban counterparts. And Cuban students attending US schools brought the game of baseball home. But baseball wasn’t for everyone.

In its December 1867 meeting, the National Association of Baseball Players barred any club with one or more colored persons from participating in their game. Unknowingly, creating a new kind of bond between Cuba and the United States.

A student at Spring Hill College in Mobile, Alabama, Nemesio Guillot, and his brother Ernesto upon returning to Cuba, founded the first baseball team in Cuba, the Havana Baseball Club.

But soon afterwards Spanish authorities, because Cuba was ruled by Spain, banned baseball as it had begun to capture the popular imagination. It had become more popular than bull fights, which Cubans were required to participate in as homage to Spain.

The ban was one more reason Cubans wanted to be done with Spain, and now playing a banned sport became a national symbol of defiance.

When Esteban Bellán, a Cuban student at Fordham University in New York and a member of their baseball team, heard about the banning. He decided not to return to Cuba, and instead, he wanted to become the first Latin American player to play in the major leagues.

But despite the ban, Cubans continued to play, and formed the first Cuban League in 1878, bringing Esteban back to Cuba, playing for Club Havana. The Cuban League played from November to May, making it a great winter league for US players, so Esteban could play in both.

Cuba’s plea for independence got some unsolicited help when the US began the Spanish-American War. In 1898, at the defeat of Spain, Puerto Rico, Cuba, the Philippines, and Guam were seated to the US for $20 million, and Cuba was free from Spanish rule.

That brought new opportunities for them to play US teams.

Just a year later, Cuban teams started to allow black players to play in their league, thus began the integration of baseball.

By the 1880s, black amateurs and professional leagues had formed. The East Coast scene had grown the most, with Philadelphia, being the center of the baseball universe. Well, the Philly area. It wasn’t always easy to get permits to play, so Camden, New Jersey, crossed the river, saw a good number of games as well.

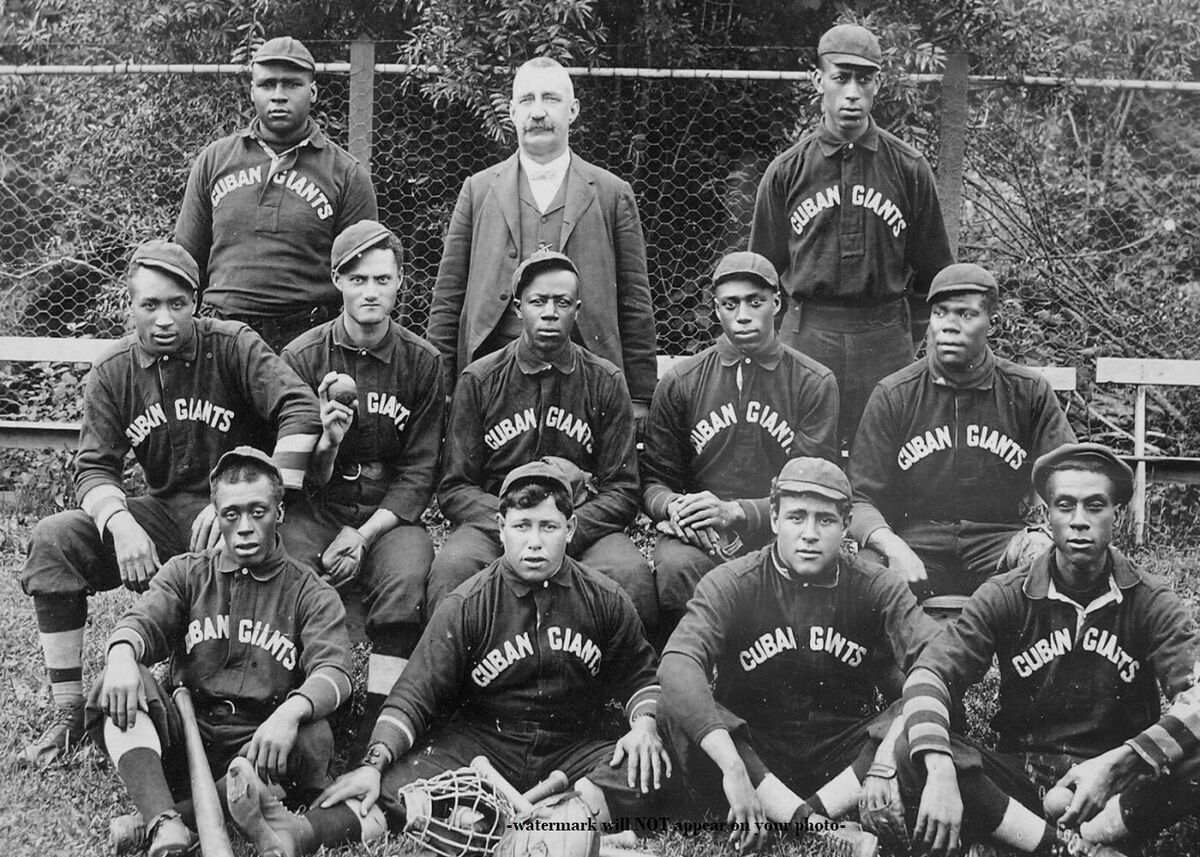

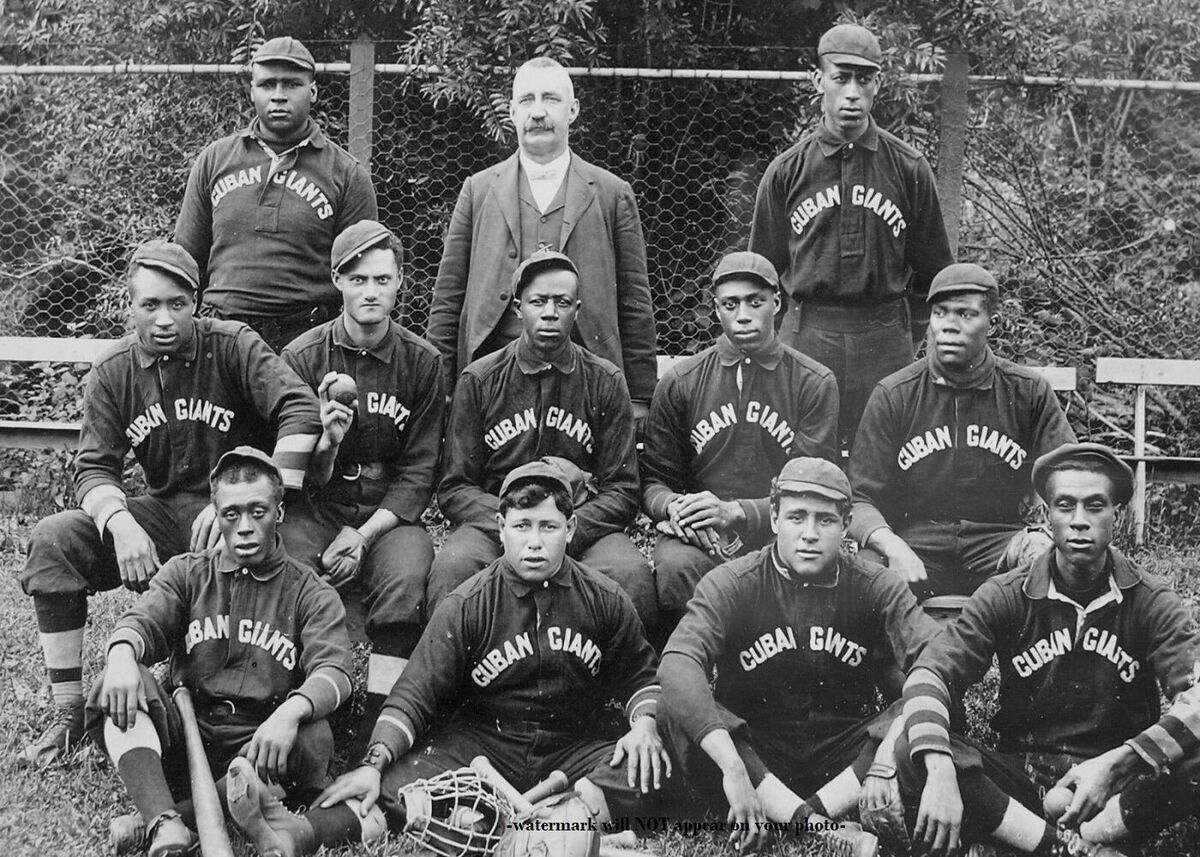

The Cuban Giants out of New York were the first professional black team, sadly choosing that name because white spectators were more inclined to watch Cubans than blacks. And their success led to the first Negro League, the National Colored Baseball League in 1887.

By 1899 Cubans were playing American teams and American teams were playing Cuban teams, thus both teams were allowing players from the other league to play on their team. For several years they played without incident, other than seeing the rise and demise of many teams over the years.

But in 1914 World War I put a crimp in the rise of baseball. In the US the need for workers in the Northern states to replace soldiers sent abroad created a migration of blacks from the US south to the north. In Cuba it caused forests to be chopped down to make way for sugar cane and core production, and for thus they needed workers.

At the end of the war it was the former pitcher of the Cuban giants, Rube Foster, who pushed to get baseball going again.

In 1920, therefore, a new Negro National League was started with the “Rube Foster” as the president. It was only a couple of years before an eastern and southern league had started, and the first colored world series was played in 1924. The Negro League games were very successful, often seeing attendance higher than major league games, even when played on the same day in the same city.

The major leagues held America’s attention as well. In 1908, the Chicago Cubs had won their second World Series, and over the next few years, players like Ty Cobb, Onus Wagner, Shoeless Joe Jackson, and Babe Ruth became celebrities.

Everybody was going to baseball games.

In 1908, a 29-year-old, 10-pan alley musician, Jack Norworth, was riding a subway to Manhattan, when he saw a billboard for a baseball game. Being a songwriter, the idea of going to a game inspired him to write some lyrics. Fifteen minutes later, he had something he really liked, and he brought it to his composer friend, Albert Von Tilzer.

When they were done, they knew they had a hit song on their hands. Lo and behold, the song quickly became a number one hit and stayed there for seven weeks. While most people only know the chorus, “Take me out to the ball game”, It really is a full song about a young lady who wants her boyfriend to take her to a game. The song famously refers to another baseball tradition, America’s first junk food, Crackerjacks.

Frederick William Rueckheim and his brother, the creators of Crackerjack, couldn’t have been happier with the song. Since creating the snack, they’d sponsored some baseball stadium scoreboards, but hadn’t yet achieved amazing success.

Twenty years prior, F.W. Rueckheim and his brother had emigrated to Chicago from Germany and were selling popcorn via a street cart. Their caramel corn was too sticky for a commercial product. But they’d developed a way to make it less sticky and had developed wax packaging to keep it fresh, and had added peanuts.

Just in time, for the 1893 World’s Fair where they would unveil their newest snack, they called Crackerjack. They called it that because at the time, Crackerjack meant excellent.

The World’s Fair was destined to be the largest event of the century. The city of Chicago outbid New York and other cities and abid to get the fair. With Marshall Field, Cyrus McCormick and Philip Armour providing some of the financing, Congress approved the fair taking place in Chicago.

The Rueckkheim brothers showed up at the World’s Fair offices in Chicago’s Rand McNally building. They signed up for a booth next to a new beers company called PABST, a new chewing gum called Juicy Fruit, and a chocolate confection called a brownie.

While the World’s Fair was a great debut, “Take Me Out to the Ballgame”, finally made Cracker Jack a hit, and stadiums all over began carrying it. That gave the Rueckheim brothers an idea. They would make baseball cards and put them in boxes of Cracker Jack.

That happened in 1914, with the American National and Federal leagues in full swing, they included a baseball card with an action photo of players from each team.

The Crackerjack ball cards didn’t include any of the Negro leagues, however. But in 1914, the black players weren’t yet household names.

It wouldn’t be until 1933, when Satchel Page and Josh Gibson were playing. The Negro League All-Star game took place at Comminsky Park and drew 20,000 fans. Many contended that the Black players were better than the major leaguers, which is entirely possible because the Black players did have a secret weapon. When the regular season was over, many of the top players would play the winter months in the Cuban League.

In 1934, there were only six teams in the Cuban League, but by 1940 there were 18. World War II disrupted baseball as much as the first one did. With most ballplayers being of draft age, the Major League teams in the US were barely recognizable during the war.

But the black players, they skewed a bit older, and with more blacks being employed by the war efforts and flush with money, the Negro League’s flourished between 1941 and 1945. So well, in fact, it forced the major leagues to consider racial integration.

Cuban teams forced as well during the time. In Cuba, having beaten Nicaragua, Mexico, and the USA, they won the 1939 amateur world series. And a few short years later, in 1946, 31,000 fans attended the opening game in Havana.

Baseball was changing.

But underneath it all, underneath the love of baseball, underneath the sugar cane trade with the US, was a feeling in Cuba that the US was an overbearing friend. While the Spanish-American war did free Cuba from Spain’s rule, it wasn’t a war they fought and won.

Many felt the fight for freedom was stolen from them. And that feeling didn’t go away as the US took over Cuba from Spain, holding onto some dominant power until 1902.

And even after that, the US reserved its right to intervene in government affairs and other things. And while the US did bring industry and train travel and communication infrastructure to make Cuba the most prosperous country in Latin America, it also dictated relationships and the price of sugar and made it hard for Cubans to feel totally independent and free.

This feeling was strongest, with sugar cane plantation owners, like Ángel María Bautista Castro y Argiz. Ángel was Spanish, a veteran of the Spanish-American war. He fought the US for Spanish Cuba. After defeat, he went back to Spain, but found no real future for cavalrymen there.

So he decided to return to the Cuba he fought for, and arrived without a cent, infuriated at the control America had. He found a job loading sugar wagons with the United Fruit Company, a U.S. based company.

Seeing all the hardwood forests being cut down to make way for American plantations to grow sugarcane, Ángel set up a shop in town to sell supplies to cane workers. That made him enough money to leave United Fruits and purchase some land.

That land was suitable for sugarcane, corn, poultry, and cattle. Ángel worked the land and got involved in many other ventures. His plantation would one day employ 400 Cubans and extend across 10,000 hectares.

His name became important in Cuba.

Along with the business, he and his wife had five kids. His son, Fidel, was born in 1926 on the sugar plantation. Having grown up in a Spanish household that appreciated education, Ángel sent Fidel to a private school at the age of six.

While an okay student, he really excelled in athletics, baseball being his favorite. His studies took him to law school in Havana, where he served as a left-handed pitcher for the school team. More interested in the social part of school, he didn’t pay a lot of attention to his studies.

He became quite passionate about anti-imperialism, opposing U.S. intervention in the Caribbean, which had infuriated his father. He even gave a speech on the topic when running for president of the school body. That speech got a mention in the newspaper. And he got the attention of Juan Bosch.

Fidel and Juan once left school to help overthrow the dictator of the Dominican Republic, and they went to the riots in Bogota, handing out anti-American pamphlets. Juan would one day go on to become the president of the Dominican Republic.

That activity led Fidel to anger, and the desire to oust the U.S.-backed Cuban leader, Bautista. On January 1st, 1959, Fidel Castro did just that.

His “army” unseated Batista from office, and in his victory speech he declared he’d make Cuba free of America once and for all.

Back a few years in 1946, at the end of World War II, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the first commissioner of baseball passed away and Happy Chandler, the governor of Kentucky resigned and took his place.

Chandler was for the integration of baseball. In his biography, he wrote that he couldn’t in good conscience tell black men they couldn’t play baseball when they just fought for their country.

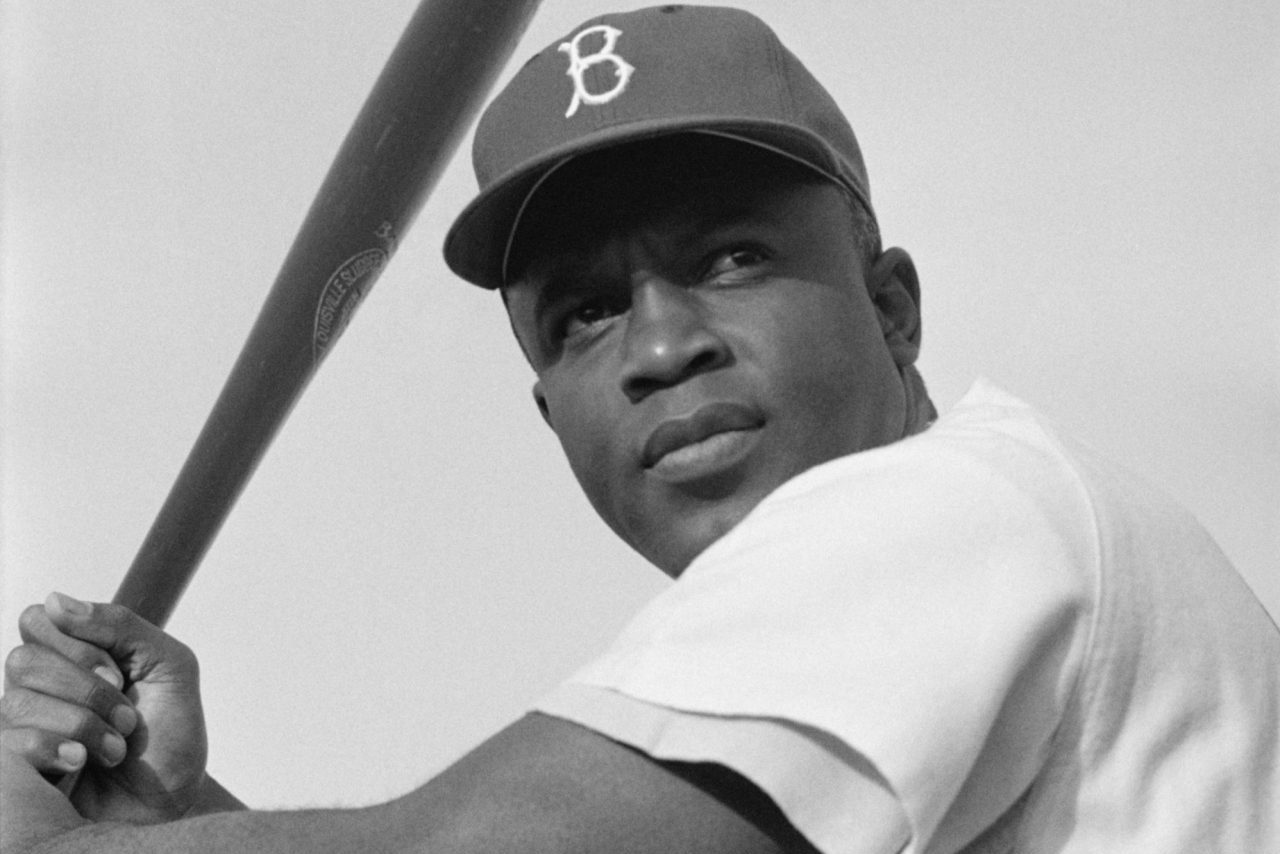

The next year in 1947, Chandler approved the contract, landing Jackie Robinson on the Brooklyn Dodgers, a landmark moment in American sports. After Jackie Robinson, the floodgates opened, and many teams integrated, taking players from college, the Negro leagues, Cuba, and other Latin American countries.

Willie Mays, Roy Campanella, Ernie Banks, Satchel Page, Hank Aaron, and Edmundo “Sandy” Amaros, from Cuba, were all early major league players after integration.

Sadly, integration spelled the end of the Negro Leagues. Black team owners were left in a pickle. They certainly didn’t want to stop players from playing in the major leagues, but they also didn’t want to lose their teams, their culture, their life.

Rube Foster, former pitcher for the Cuban giants, and head of the Negro League, said this about Jackie Robinson’s integration.

“A big part of Black Life was over, and where we had whole teams to root for, now we had one player.”

The end of the Black Leagues didn’t change much for the Cuban League. They merely switched to playing the minor league ball clubs in the US. In fact, the Havana Sugar King started the year Jackie Robinson signed.

In 1955, the Cuban people experienced something they never had before. A live broadcast of a US baseball game. While Cuba was the first Latin American country to get TV, live International broadcasts were unheard of.

But this one was special.

It was the 1955 World Series, putting the Dodgers against the Yankees. The Dodgers had Jackie Robinson, Sandy Coefax, Tommy LaSorda, Roy Campanella, and Cuba’s own Ed Mundo “Sandy” Amaros.

That live broadcast was made possible by outfitting a Cubana airline DC-3 with elite relay transmission equipment and flying it in circles between Key West and Havana for four hours. A sign of the technology hungry Cuban people.

The entire country got to see Amaros.

You must understand what this means. The Brooklyn Dodgers had never won a world series. They had lost five to the Yankees since 1941. And it looked like more of the same in that seventh game, when with two-on base in a 2-0 Brooklyn lead, Yogi Berra was up to bat.

Berra reached across the plate from his left-handed stance and hit a fly ball down the left field line. The entire country of Cuba gasped. Amoros was there, playing a little bit closer to center field. When he heard the crack of the bat, he took off. He ran toward the left field line.

Unfortunately, Amoros is a left-handed player, which meant the ball glove was in his right hand.

As it was on the run, the ball dropped into his outstretched glove, and he made a series of dance steps to miss the low fence before him.

He wheeled and threw to shortstop P.E. Reese, who threw to Gilfaw Hodges at first. It was a double play. Amaros saved the game, and the Dodgers won the series.

The cheering from Cuba sounded like Krakatoa. The US-Cuba baseball relationship couldn’t have been better.

Just over three years later, Fidel Castro would take over and change Cuban baseball and Cuba forever. In 1959 and ’60, Cuban baseball was unsure of its future as Castro began to nationalize industries. Fortunately, the Havana Sugar Kings won the minor league world series that year, defeating the Minnesota Millers delaying the inevitable.

In 1960, feeling the end near, many Cuban ballplayers like Jose Cardinal fled to the U.S. prior to the clamp down.

Before the year was over, Castro ended all professional sports in Cuba in favor of local amateur sports aimed at increasing comradery and fitness. The Havana Sugar Kings, a US minor league team, moved to New Jersey, where they became the farm team for the Baltimore Orioles.

Also in 1960, John F. Kennedy was campaigning for president. Baseball was in his blood as well, as he and his father had both played on baseball teams in school. He also had gotten Willie Mays and Stan Musial to campaign for him.

While he was busy campaigning, President Eisenhower was deeply involved in the changes taking place in Cuba.

In June, Castro took over the oil ore fineries, some of them owned by US companies, in order to process Russian and Venezuelan oil. Eisenhower then cut off the sugar quota. Castro then took over the mills and public utilities. Eisenhower banned all exports to Cuba. Castro evicted the US embassy, and then the Russian ambassadors and envoys started making trade deals with Castro.

But it was our failed attempt to remove Castero from office by way of the Bay of Pigs invasion that had invited Russia to help provide defense. Shortly thereafter, in October of 1962, a U2 spy plane took photos from high above the island of Cuba.

Analysts looking over the photos saw what appeared to be a military operation, a secret military operation, possibly with nuclear missiles. But Cuba didn’t have this technology.

How could they be sure? Analysts concluded this new base must be the Soviets. They for sure knew it wasn’t the Cubans. They knew because of one thing they didn’t see in the photos.

Baseball diamonds.

Cubans played baseball, and this installation looked like it had soccer fields. Upon this confirmation, began the most tense 13 days in the history of the Cold War, now known as the Cuban Missile Crisis.

If it weren’t for baseball, it’s possible the analysts would have waited for more confirmation, perhaps even deciding what they were seeing was harmless. But the result of the Cuban Missile Crisis was the Soviets removing those nuclear missiles that were just 90 miles from Florida.

Professional baseball has never returned to Cuba, though in 1995, the Baltimore Orioles, former pro team associated with the Sugar Kings, played an exhibition match against Havana and lost.

Jose Cardinal, the last player to leave Cuba before Castro’s shutdown, made it to the major leagues and got to play for his dream team, the Chicago Cubs.

In 1973, he was Chicago’s player of the year. Jose was a unique player whose large afro visibly poured out from under his ball cap, creating a new trend among black youth. In fact, when the Cubs finally won the World Series again in 2016, over the 108-year drought. He received a special invitation to the White House.

The invitation came from the First Lady Michelle Obama. Jose was her idol and she too wore her hair like him. The moment that hit me the biggest in this story was the words of Rube Foster.

“The integration of baseball, I have always thought, was momentous, was overdue, was right. But an entire culture had developed. When 20,000 and 30,000 fans show up to watch a Negro League game, that is a stadium full of smiles, joys, and cheers.”

The idea that that joy of rooting for teams was replaced with rooting for one guy was eye-opening. There truly are many sides to one story.

Now, let me tell you about the stories that hit the cutting room for. Early on, we told the story of Paul Harvey, my favorite radio broadcaster. Part of that tale was Paul spending time in Hawaii investigating. After World War II had started, he had a hunch, something big was going on in the Pacific Front. He spent seven or eight months there in 1941 before deciding to head back to California. Doing the research for this story, I learned that Jackie Robinson was in Hawaii at the same time playing football on an integrated team called the Honolulu Bears. Both Paul Harvey and Jackie Robinson left Hawaii on the same day headed for California on the SS Lurliner exactly two days before the invasion of Pearl Harbor.

Did they meet? The world will never know.

CUTTING ROOM FLOOR

To hear all the stories that hit the cutting room floor, you have to listen to the episode.

ABOUT THE SHOW

Let us tell you the story of the 20th Century, by tracing each event back to the original decisions that shaped it. You’ll quickly find out that everybody and everything is connected. If you thought you understood the 20th Century, you’re in for a treat.

Tracing the Path is inspired by storytellers like Paul Harvey, Charles Kuralt, and Andy Rooney.

INTERCONNECTED EPISODES

|

Bob’s Swedish Candy Canes Candy Canes are Swedish . . . with an American twist |

|

How the Hostess Twinkie Survived Death Twice Did you know the toaster was invented before sliced bread? And Twinkies almost didn’t survive the 80s. |

|

The Official Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon It just so happens Tracing the Path is friends with the creator of the Six Degrees, and he’s only 1 degree away. |

|

The Surprising Life Story of Paul Harvey Pearl Harbor, Pilot, Chicago and Coca-Cola; The World’s Most Prolific Radio Man |

|

The Wizard of Oz’s 30 Year Miracle Beyond every American watching the Wizard Of Oz, this story has ties to Frank Lloyd Wright. |

|

1848 The Year Halloween Began Have you ever heard the origin of Halloween? |

|

How Negro League Baseball Solved the Cuban Missile Crisis It was bittersweet to see the Negro League end. So many goods, so many bads. |

SEE THE BIBLIOGRAPHY

SUBSCRIBE AND LISTEN (FOR FREE!)

RATINGS & REVIEWS

If you enjoy this podcast, please give it a rating and review.Positive ratings and reviews help bring Tracing The Path to the attention of other history lovers who may not be aware of our show.