TRACING THE PATH PODCAST

This story intricately traces the surprising and complex origins of the candy cane, revealing that its existence is a testament to an unexpected chain of historical events and diverse figures.

It begins by exploring the ancient practice of chewing tree resins for breath freshening and the medicinal importance of mint, culminating in the commercialization of peppermint oil. The story then weaves through the lives of seemingly disparate individuals: Mexican king Antonio López de Santa Anna, who inadvertently kickstarted the chewing gum industry; Swedish maidservant Amelia Ericson, who created the iconic red and white peppermint candy sticks (polkagris) out of necessity; and American entrepreneur Bob McCormack, whose brother-in-law, Catholic priest Gregory Keller, invented the machine that perfected candy cane production.

Ultimately, the story demonstrates how a global tapestry of innovation, personal struggle, and cultural exchange converged to create the beloved holiday treat we know today.

Audio Hour:

If you run an activity group, classroom or “audio book club”, click here for more information on using Tracing The Path.

Throughout the episodes, every tune is somehow related to the topic. In the Twinkies episode, for instance, the discussion of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops Baseball team concludes with “Take Me Out To the Ballgame”.

How many do you recognize? And harder, how many can you name?

It Started with Black Mitcham Peppermint

For candy canes to make it to your mouth, it would take a Mexican king, a Swedish maidservant, a billionaire baseball owner, and a Catholic priest.

It’s hard to imagine a world without minty fresh breath. But it wasn’t until 1781 that anyone even thought about it. Prior to that, the ancient Greeks and Mayans are known to have found comfort in chewing the resin or sap of the mastic evergreen tree.

Mastic trees had a resin that was clear with an evergreen essence. Manora trees and sapadia trees provided similar benefits. The sapadia tree produced a gum or sap or resin called chikla that was chewed as a medicine and the North American Indians used the sap of spruce trees.

Not far behind that was the chewing of leaves.

An Egyptian table back in 1550 even shows mint leaves being chewed as a medicinal tool. While 1550 seems like a long time ago, it would be only 70 years after that that the pilgrims on the Mayflower landed in the new colonies.

Mint was important enough they brought it as a medicine for toothaches, coughs, upset stomach, and headaches, making a pretty good case that culturally the benefits of mint were not isolated to Egypt.

In 1638, a lesserknown group led by the Swedish West India Company also landed and set up a colony in the New World. While it only remained until 1655, It left a lasting impression in the hearts and minds of the Swedish.

One thing that the Swedish and the Brits had in common were their sweets and candies. Both enjoyed pulled sugars, also known as candy sticks.

1750 is the first year in Surrey, England’s recorded history that black Mitcham peppermint began to be commercially harvested. And while many would expect it to be black, it was actually a purple that was so dark it looked black.

The commercial peppermint crop was entirely reserved for pharmacists and doctors in the field of medicine, and getting use out of it was so complicated, most people didn’t even consider it.

Mint is not actually ready to be harvested until it is 2 ft tall, and then it is cut and then properly dried. Then the dried leaves are steamed to distill the oil from the plant. The result is gallons and gallons of peppermint oil and water from the steam that is then boiled until the water has evaporated, leaving only a little bit of peppermint oil.

One of the companies buying commercial peppermint oil was also one of the first to create a medicine that produced fresh breath. The company had five distinct products.

- Benoids for throat and chest congestion.

- Zenoids for digestion,

- Cyphoids as throat lossenes,

- Notoids as voice protectors,

- Altoids with peppermint oil for stomach calming.

And like other medicines, they were sold in a protective tin. Which brings us to the first hero of our story, however, not everyone would label him a hero.

And Then Came Santa Ana, of Mexico

He was born on February 21st, 1794 in Veraracruz, Noea, Espa, known as Mexico today. His name was Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón.

Antonio, as he was known, was born to a upper class parents. But because his family was native to Mexico and not one of the Spanish Conquistadors, they had limited ability to rise and prosper in their jobs with Spanish rule.

But despite being pushed down by this culture, Antonio still joined the Spanish Army rather than stay and be a shopkeeper with his dad. Shortly after he joined the army, the cholera epidemic hit and wiped out much of his Spanish army comrades.

And in a strange twist of fate, the native status that kept his family from getting job promotions was now the same trait preventing him from getting cholera. And because of that, he was able to rise in rank over time.

At the age of 16, Antonio fought in the Mexican War of Independence on the side of Spain, trying to put down the Mexican Rebellion. During that war, he found himself often in an area called Texas.

However, his ties to Spain changed in 1812 when the Spanish King Ferdinand had been ousted and a new constitution put in place. Antonio and others around him contemplated their options and decided to switch sides.

Now fighting for Mexico.

In Spain’s final battle to take Mexico, it was Antonio who helped defeat them, becoming a national hero overnight.

In 1833, he became king of Mexico.

Over the next decade, he would be king five different times.

But by now, Antonio wasn’t the name most people knew and understood. To Mexico, he was Santa Ana.

While Santa Ana was loved by the people, politically he was often on the outskirts looking in. And for this reason he was important to the US.

After each one of his stints as king, he would find himself defeated and exiled in a different place like Jamaica or Cuba or even the United States.

In 1867, that’s when he found himself living on Staten Island in New York City, trying to raise enough money to command one last army and return to Mexico.

Santa’s Gum

One thing he didn’t like about Staten Island was the difficulty he had in finding things that were important to him. One of those things was chicla, the sap or resin that he liked to chew. Native Mexicans grew up with the tradition of chewing sap of the sapadilla trees. And so he had to have it delivered to him.

And being the foreign dignitary that he was, he had great quantities delivered. Seeing the size of the delivery, made him wonder if he could somehow make money from the Chicla to help finance his new army.

During his time on Staten Island, he had come across an inventor named Thomas Adams. So, he sent word to Thomas Adams asking if he would come to his house. Thomas found the Chicla immediately interesting, very much like rubber.

So, Thomas began experimenting to see if he could make an alternative to rubber. Rubber was very expensive. An alternative could be of great demand.

He tried to make toys, masks, boots, and bicycle tires, but they all failed. Not sure what to do next, he got an idea when he was at a drugstore. Seeing a young girl buying paraffin wax to chew on, and recalling that Santa Anna had also used Chicla as a chew made him think he could make a chewing gum.

And he did, naming it New York City Number One Gum.

Then in 1869, he opened the world’s first chewing gum factory and began selling it to retailers.

The gum was a hit.

The gum was so successful, he designed a machine that could mass-roduce it and got it patented in 1871. And then in 1884, he put out his first flavored gum, Blackjack, the flavor of black licorice.

In 1888, he put out his next flavored gum, Tutti Frutti, to be sold in another invention of his, the gumball vending machine.

But neither of those were peppermint, which brings us to the next hero of our story, and gets us one step closer to the most famous Peppermint, the candy cane.

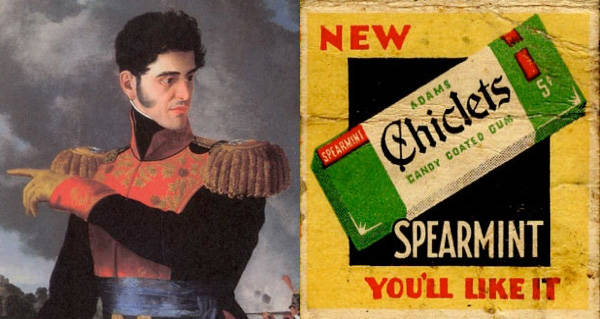

Hotchkiss’ Peppermint Oil

Around the time Santa Anna had been Born in Mexico 1810, Hiram G. Hotchkiss was born in Onieda, New York. Hiram grew up on a farm, learning everything he could from his father.

But at the age 18, his parents passed away, leaving the farm to him and his brother. Hiram and his brother expanded their flower and milling business, the business their parents had started. And while it was succeeded, Hiram branched out to make headway in the essential oils business, one that required farming experience.

He moved to nearby Lyons, New York, right on the banks of the brand new Eerie Canal, and began buying peppermint plants from farmers who found it growing wild on their property.

By 1839, he’d been able to turn it into a business.

But as successful as he was at making peppermint oil, he was finding harder to find buyers of peppermint oil. Using the canal and the Hudson River, he began making trips to New York City to pedal the peppermint oil. But everyone who was using peppermint oil was getting it from Europe, which at the time was the capital of peppermint, mainly from Hamburg.

Not sure what else to do, he sent a sample of his oil to Hamburg, Germany to be tested and certified by someone. Surprisingly to him, Hamburg sent back a letter stating that his sample had been rated purest in the world.

And because of that, in 1851, his oil won awards at the International Exposition in Germany, the first of many awards. And when the award arrived in Lyons, everyone wanted to see the signature of Prince Albert himself.

Being on the Eerie Canal, it wasn’t long before he ramped up production, and he had special blue branded bottles to dip his peppermint oil in. By 1860, Hiram Hotchkiss was producing 1/3 of all the peppermint oil in the US.

Nevertheless, in both the US and Europe, peppermint oil was still primarily being used for medicinal purposes.

One person knew that better than anyone. Amalia Eriksson from Sweden.

Amalia Eriksson -The Founder

Amalia was born in 1824, but by the time she was 10 years old, she’d lost both her parents to the raging cholera epidemic.

Thus, she became a maid servant as part of the system.

And as if she needed more tragedy, she fell in love in 1857, got married, and had a child, only to have her husband die from dysentery before their second anniversary.

And then her daughter became ill.

She didn’t have enough money for doctors and medicines, so she bought peppermint oil and experimented with ways to feed it to her daughter. Knowing children loved candy, she’d combined the peppermint oil with sugar and vinegar, among others, to make hard candy rods.

They didn’t help cure her daughter’s illness, but her daughter loved them, so Amalia started selling them to friends and neighbors to support herself. On top of that, she’d make and sell baked goods as well.

And while it was almost impossible for a woman to own a business, there were special considerations for poor widows who could support themselves by making things with their hands.

The city of Gränna, Sweden, took this into account when they saw her request for a business license to make and sell candy and baked goods. And on January 10th, 1859, she was awarded a business license.

The candy sticks she’d made for her daughter were a huge hit.

They were a combination of a thin red rod and a thin white one twisted together with a sweet peppermint taste.

She named them Polkagris, which meant dancing candy. This red and white peppermint candy from Gränna would become so popular in Sweden that the crowned prince Adolf and Princess Ingaborg would visit the shop to get some for themselves.

It was at the same time period that European citizens, especially Swedes, were experiencing hardships of their own.

The Irish had just come through the great potato famine, which saw millions fleeing to America.

Sweden also had agricultural problems, and a bigger fight was their freedom of religion. For the Swedish people, the colony that had been set up in America in 1638 had created a strong long and lasting interest.

While only 700 Swedes had moved there, the idea of complete religious freedom and homesteading were a thing of legend. So slowly, Swedish people began relocating to the new world.

So much so, the US Census Bureau tallied 800,000 Swedish immigrants in the 1869 census.

And with them, they brought family and holiday traditions like the red and white twisted peppermint candies called Polkagris.

That same year, 1869, was the year Thomas Adams opened the world’s first chewing gum factory in New York City and had gumball vending machines in the subway stations. And Hotchkiss, near the Eerie Canal, was now producing one third of the nation’s peppermint oil.

Which brings us to the fourth hero of our story.

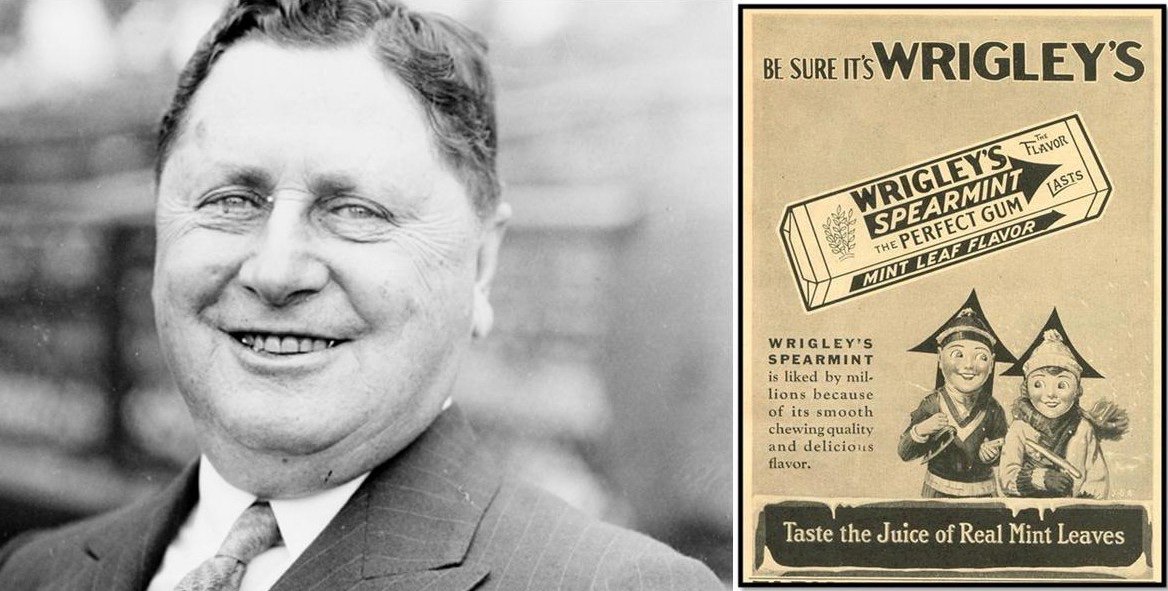

William Wrigley’s Gum

William Wrigley Jr. was 8 years old in 1869.

Wrigley grew up in Philadelphia in a Quaker family of English descent. The Quakers were known for making and selling handmade goods.

The Wrigleys sold soap and at the age of 13 William went on the road as a traveling salesman selling soap all over New England. At the age of 19, he was confident in his sales skills and relocated to Chicago to go in business for himself.

If he was going to sell soap, he couldn’t stay in New York and compete with his family. In Chicago, his soap selling business took off. Because he’d already tried every sales tactic there was, he knew exactly how to close deal.

With each soap purchase, he dangled a free bonus.

In Chicago, he’d started by offering a free can of baking powder with every sale. Baking powder was relatively new, and in some places only chemists and pharmacists sold it. So, the baking powder was actually a bigger draw than the soap.

Therefore, Wrigley switched his model.

He started making and selling baking powder.

But he needed a different bonus than a free bar of soap. Having seen the gumball vending machines in New York, he thought gum would be a good offer. But just like his soap trial with the baking powder bonus, the gum was a bigger draw than the baking powder.

So in 1891, Wrigley switched industries again, this time manufacturing chewing gum.

Doing a little research, he learned that the New York gum was made from from South American chicla,whereas in Chicago, the kids were mostly chewing paraffin wax.

To sell large quantities, he knew he’d have to sell it to the retailers, which meant he needed a little clout and some free bonuses. And he knew exactly how he would get clout.

So he launched a fruit flavored gum called Juicy Fruit at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair in hopes of getting some sort of new product award. to put on his label. He had a booth alongside other brand new products like Aunt Jemima, Cracker Jacks, Pabst Blue Ribbon, the Zipper, and even a Ferris Wheel.

When it was over, he hadn’t won an award, but his gum had now been featured at the Chicago World’s Fair, and retailers could walk away with a coffee grinder, display stands, or a clock as an incentive to purchase.

And so, by 1908, Wrigley was generating $1 million worth of gum.

For Thomas Adams and a couple other small gum makers, competing with Wrigley was going to be hard. So, they toyed with the idea of joining together.

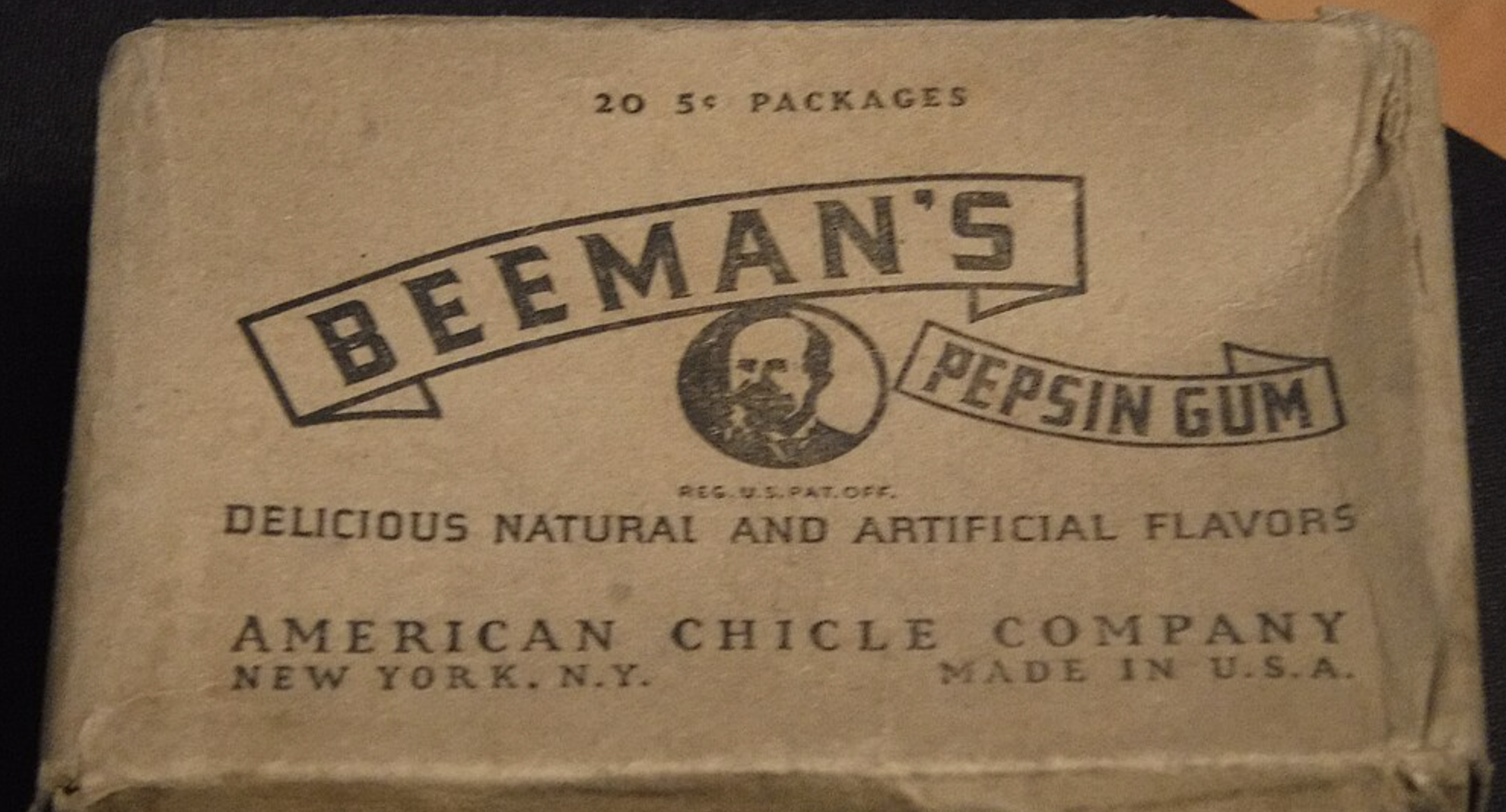

American Chicle Company

One of those was Franklin V. Canning. He knew a dentist back in 1869 had patented a healthy teeth chew that was a mixture of nap the chalk and licorice root. Franklin thought chicla would make a better base and cinnamon a better flavor.

So he combined the words dental hygiene into one new name dentyne and made Dentyne Gum.

Also around that time William White a Cleveland Ohio candy store owner accidentally ordered a barrel of the chicla Santa Ana liked from Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. He didn’t know what to make of it, but learned he could make it chewable.

So, he added a little sugar and some peppermint oil and created the first peppermint gum he called Yucatan Chew.

And he teamed up with a local friend, Dr. Bean, and made another gum that had Pepsin in it, which was a digestive enzyme, which they called Dr. Bean’s Pepsin Gum.

And then closer to New York, just south in Philadelphia, Frank Fleer had started a confection and candy company. He also liked the chicla Thomas Adams and Santa Ana had introduced and thought it would be fun to take small pieces of chicla and cover them with candy.

He did that and called them Chicklets.

Well, Frank Fleer and Dr. Bean and William White, Franklin V. Canning and Thomas Adams got together and formed the American Chicle Company.

In 1899, Yucatan Chew, the only peppermint variety of the bunch, got harder to make in 1900 because a plant fungus had arrived, killing off most of Hotchkiss’ plants and any other peppermint growers in the Northeast, which led to much higher demand in other places, making the peppermint farmers in Washington and Oregon now the nation’s new source of peppermint oil.

By 1912, peppermint treats would begin to surface again.

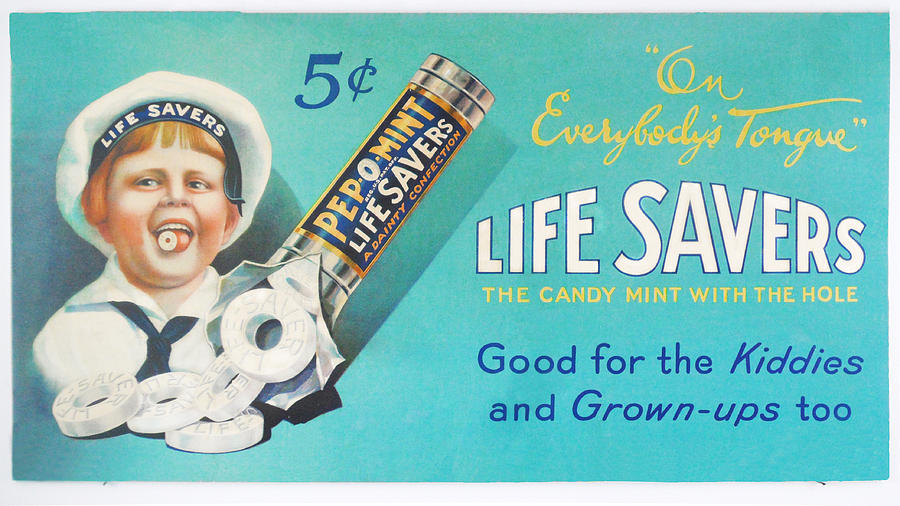

The Arrival of Peppermint

A little company called Life Savers debuted a new version called Pep-O-Mint, and Wrigley himself debuted a peppermint flavored gum called Double Mint.

It wouldn’t be until 1919, however, that peppermint became associated with Christmas. And sadly, there isn’t a romantic tale or reason. Prior to 1919, There just wasn’t enough peppermint candy to detect a pattern.

But peppermint was harvested in the summer. After drying and steaming and distilling and distribution, most makers would not get the oil until the fall.

And the making of hard candy didn’t work as well in the summer heat, so it too waited to appear often in November.

But the years 1919, 1920, and 1921 could be considered the unofficial golden era of peppermint.

Not only did Wrigley perform his most audacious stunt of mailing three sticks of Peppermint Gum to 7 million people, but three of the most famous peppermint treats came into existence.

To start, Henry Kesler decided to open an ice cream shop in central Pennsylvania. His shop sold ice cream cones and waffles, but he knew knew winter months would be slow and started looking for non ice cream treats to add to his menu.

One product that he had heard about was Kendall cakes from London. The Kendall cake had been created in 1869 by Wiper and Sons Confectionary Company.

It was a peppermint confection covered in chocolate that had been marketed as an energy bar. While it wasn’t as famous then, Kendall cakes would get worldwide notoriety when Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay ate them atop Mount Everest.

And then when Sir Earnest Shackleton took them on his expedition to Antarctica.

But for Henry Kesler, a chocolate covered mint cake was a dream confection. After experimentation, he started his selling his own little chocolate-covered mint bars.

In 1922, he decided that to name them after his town, which was located halfway between Baltimore, Maryland, and Hershey, Pennsylvania. a town called York and his mint confection, York Peppermint Patty.

That same year, 1920, in Wrigley’s hometown of Chicago, a soldier from World War I with $1,800 of soldier pay burning a hole in his pocket decided to open a candy store.

Andrew Carmelos wanted to make chocolates men would buy for their wives. But after a few years, he discovered a problem they don’t teach in business school. Men didn’t want to give candy in a box that featured another man’s name. Andrew, or rather “Andy’s Candy” needed a new name.

He wanted something exotic like the snowcapped mountains in Peru. So, he changed the name from Andy with a Y to Andy with an E, like the mountains, and created a snow capped mountain peak logo.

And his most famous chocolate was a green peppermint center covered with chocolate that he called Andes Créme De Menthe.

Which brings us to the most famous peppermint candy of them all.

Candy canes.

What’s more peppermint than a red and white striped candy cane? No one knows them better than the town of Gränna, Sweden, where Amalia Eriksson created Polkagris.

Amalia’s red and white striped peppermint sticks became so important that in 2022 they received a designation few products do in the world. They received “Geographic Protection”. The European Parliament set forth protection that states . .

“even if you use the exact same recipe as Anna did in 1859. Unless you make it in one of the shops in Gränna, you cannot call it Polkagris.”

It’s basically the same law that protects Champagne. If your sparkling wine isn’t made in Champagne, France, you can’t call it Champagne. While Polkagris is red and white striped peppermint candy, it’s not exactly a candy cane.

Some say the candy cane dates back to 1670 when a church man decided to give candy to the children at church to keep them quiet. But to make it more palatable for the church, he decided to put a crook in the top of the cane to resembled a shepherd’s staff. But this is largely a folktale.

There isn’t much to back it up.

Besides, bending hard candy into that candy cane shape was very difficult back then and resulted in many, many broken canes.

There’s also a story from 1847 where a German immigrant in Ohio, Augustus Imgard, longed for his holidays to be like the ones he had in Germany. And thus he cut down a blue spruce tree, drug it home through the streets of his town, and decorated it with candy canes.

And while this tale is widely shared with little evidence to refute it, Augustus Imgard was probably not using the red and white striped candy cane you know and love. But a white pulled sugar stick that he fancifully tied to the treere’s limbs.

In fact, when you look at historical pieces of pop culture, like postcards and books, there aren’t red and white candy canes depicted until after 1900.

Prior to that, they were just white.

The Infamous Candy Cane

That is until a lad in Birmingham, Alabama, grew up knowing he was going to make a career out of candy. And his specialty as a kid was making his own version of white and red pulled sugar sticks, twisting while they’re hot and bending the top in the shape of a cane.

He loved making them so much he wanted to do it as a business.

And while on a trip, he visited Albany, Georgia, and instantly thought it would be a good place to start a candy company.

So, in 1919, grown-up Bob McCormack opened Bob’s Candies.

One of the things he sold in his shop were the Whitman’s Chocolate Sampler Box. And what he loved about them were the special packaging that each compartment gave the chocolates and the cellophane wrapper.

Cellophane was very new. Having been invented in Amalia Eriksson’s Sweden in 1908, Whitman’s was the first American manufacturer to import it.

In fact, they were the largest importer of the US until the cellophane company in Europe sold the manufacturing and marketing rights to Dupont in 1923.

That’s when Bob ordered it and invented a package for his candy canes so they wouldn’t break during shipping.

Bob was the first manufacturer to individually wrap candy in cellophane.

While Bob McCormack had a great packaging for his candy canes, they were still very difficult to make.

During the 1930s, the candy canes sold well, but the government rationing of sugar during World War II meant the candy canes had to be put away, to which Bob focused on selling peanut products.

But when World War II was over and the price of sugar dropped, Bob asked his brother-in-law, Gregory Keller, if he’d come help.

Gregory had been a Catholic priest since 1919 and had some time to help out.

In 1952, he changed the world.

He invented a machine that twisted the red and white peppermint sticks and added a bend at the end. Perfect every time.

Not only could Bob produce thousands more, but he also eliminated a ton of broken candy waste that came from making candy canes.

Soon, millions and millions of candy canes would be sold under the Bob’s Candy’s name.

The United States produces around 1.76 billion candy canes annually as they are a key part of the Christmas season. 90% of those are sold between Thanksgiving Day and Christmas.

And while the world now had peppermint candy canes, peppermint gum, and chocolate peppermint confections, the story isn’t quite over.

Finally, in 1966, Charles Schultz, the creator of Charlie Brown and the syndicated Peanuts cartoon, was introducing a new character to the series.

He was introducing a smart lady, a thinker, and an athlete. And after seeing a bowl of peppermint patties on his living room coffee table. He thought they’d make a perfect name for his new character.

But perhaps her name should have been Peppermint Amelia.

CUTTING ROOM FLOOR

To hear all the stories that hit the cutting room floor, you have to listen to the episode.

ABOUT THE SHOW

Let us tell you the story of the 20th Century, by tracing each event back to the original decisions that shaped it. You’ll quickly find out that everybody and everything is connected. If you thought you understood the 20th Century, you’re in for a treat.

Tracing the Path is inspired by storytellers like Paul Harvey, Charles Kuralt, and Andy Rooney.

INTERCONNECTED EPISODES

|

Who Killed the American Dream The Day the Music Died is a lot more than a song. It’s the story of a nation in crisis. |

|

Why They Gave Charlie Brown a Tiny Tree The Story of A Charlie Brown Christmas, the music, the cartoon and Coca-Cola |

|

Why Rand McNally’s Route 66 Started with Camels You’ve heard the story about Roman Wagon Ruts, right? That’s not this. |

|

How the Hostess Twinkie Survived Death Twice Did you know the toaster was invented before sliced bread? And Twinkies almost didn’t survive the 80s. |

|

The Wizard of Oz’s 30 Year Miracle Beyond every American watching the Wizard Of Oz, this story has ties to Frank Lloyd Wright. |

SEE THE BIBLIOGRAPHY

SUBSCRIBE AND LISTEN (FOR FREE!)

RATINGS & REVIEWS

If you enjoy this podcast, please give it a rating and review.Positive ratings and reviews help bring Tracing The Path to the attention of other history lovers who may not be aware of our show.