Cholera, Margherita Pizza and The Godfather

This episode, “The History of Pizza,” traces the fascinating journey of pizza from its origins as a humble peasant food in Naples to its global prominence, emphasizing how historical events and cultural shifts shaped its evolution. The narrative highlights key moments like the introduction of tomatoes to Europe by Hernan Cortez, their initial distrust, and eventual integration into the Neapolitan diet, particularly aided by the volcanic ash-rich soil around Vesuvius.

It further details how cholera epidemics in Naples inadvertently led to pizza becoming a staple for the lower classes and how Queen Margherita’s endorsement significantly boosted its appeal, leading to the creation of the iconic Margherita pizza. Finally, the text explores pizza’s spread to America through Italian immigrants, connecting its rising popularity to the success of Italian-American cultural figures and even major historical figures and events like World War II and famous films that helped weave pizza into the fabric of American society.

Audio Hour:

If you run an activity group, classroom or “audio book club”, click here for more information on using Tracing The Path.

Throughout the episodes, every tune is somehow related to the topic. In the Twinkies episode, for instance, the discussion of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops Baseball team concludes with “Take Me Out To the Ballgame”.

How many do you recognize? And harder, how many can you name?

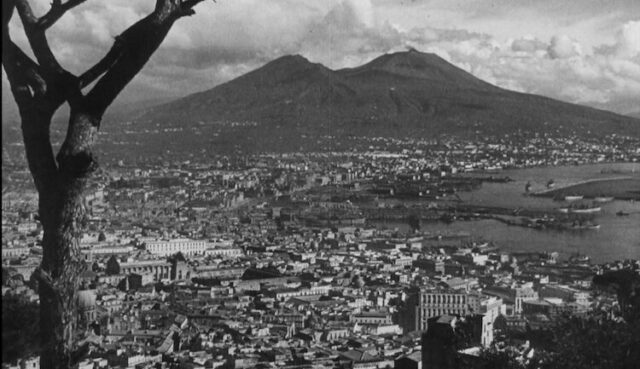

The 18th century began the tomatoes jump into the Italian diet. Naples was the first to integrate tomatoes, but they had a secret weapon. Their soil was more suited to tomato production than most other places on earth. Their soil had been mixed time and time again, with the lush ash from out Vesuvius eruptions. The mineral content of the soil was perfect for tomatoes.

Tomato sauce entered the Italian kitchen early, as referenced in the 1790 cookbook L’Apicio Moderno by Chef Francesco Leonardi, a prominent Italian chef.. It suggested making the sauce for merchants who were going to be taking long expeditions at sea.

Chef Lombardi named his tomato sauce, a name that meant seafaring. You know it well. Marinara.

It wasn’t long before tomatoes and marinara were used as toppings on their traditional flatbreads. In 1807 there were 54 pizzerias in Naples, who turned this ancient flatbread practice into a staple food. Naples pizzerias became known throughout Italy and attracted the curious.

Alexandre Dumas visited Naples several times and in 18, penned his travel stories in a book, Le Corricolo. He encapsulated his interest in pizza like this.

“The pizza is a kind of talmouse like the ones they make in Saint-Denis. It is round, and kneaded from the same dough as bread … There are pizzas with oil, pizzas with different kinds of lard, pizzas with cheese, pizzas with tomatoes, and pizzas with little fish. At first glance, pizza seems like a simple dish, pizza with oil, with bacon, with lard, with cheese, with tomatoes, with sardines. It is a gastronomic thermometer of the market, increasing or decreasing with the price of the toppings and availability during the year.”

Dumas was not well known outside Italy in 1841, but all that changed in 1844 when he would publish “The Count of Monte Cristo” and the “Three Musketeers”.

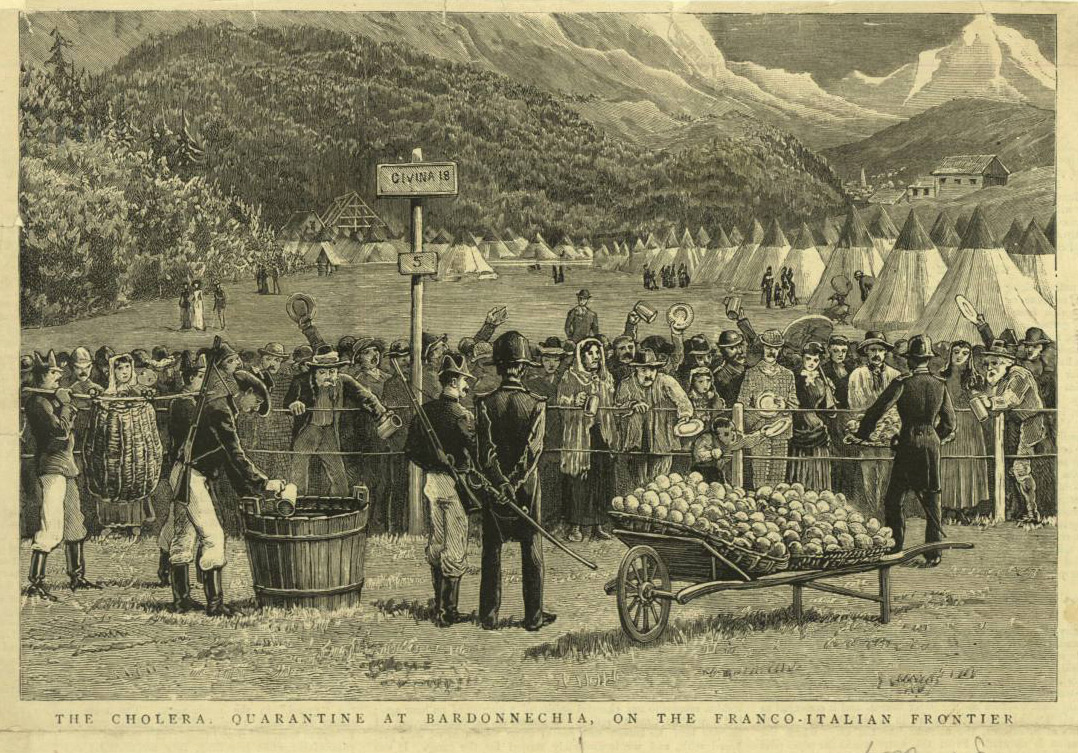

By 1844, travel to Naples had begun to slow, as the first round of cholera devastated the city. Naples had been the largest city in its region, perhaps the largest in Italy. At the beginning of the 19th century, Italy was three separate states, but over the course of 71 years they unified to become today’s country of Italy, housing the capital of the Catholic Church.

While Naples was the most likely candidate to become the capital, Vesuvius eruptions and Calvara led the leadership to choose Rome, leaving Naples in the dust. Pizza was then relegated as the pauper’s food, served on the streets of the cholera infected living cemetery.

With no real medical knowledge of cholera, citizens had no understanding of how to prevent it. They stopped trusting doctors in the government and relied on logic. Thinking it might be a sanitary issue, they resulted in relying on wine and deep frying their pizza. To this day, fried pizza remains a staple of Naples Street vendors.

The idea that pizza was peasant food was never more clear than when stated so in an 1876 book titled “Il Viaggio per l’Italia di Giannettino” written by an aristocrat from Florence. In its description of pizza it says, “It is a focaccia made from leaven bread, which is toasted or fried. On top of it, they put a sauce with a little bit of everything. When its colors are combined, the black of the toasted bread, the sickly white of the garlic, the green yellow of the oil, and bits of red from the tomato. It makes pizza look like a patchwork of greasy filth that harmonizes perfectly with the appearance of the person selling it.”

The aristocrat from Florence, who penned such a scathing book, would become famous a few years later. You may not know the name Carlo Collodi, but you do know the book that made him famous, the one and only story of Pinocchio.

Politically, times in Italy were in turmoil. Unification started in 1871. The king was almost assassinated in 1878, and Italy’s relationship with neighboring countries was strained. The first First Lady of Italy took it upon herself to network, promote Italy, and build a loyal following of the monarchy.

In 1899, she decided to make a dangerous trip to Naples, where cholera had killed over 40,000 people, and the city was rebelling against doctors and the government. Naples was honored to be visited by the Queen and gave her the most beautiful reception.

To show she was a queen of the people, she tried to dawn local folk clothing and eat the local fare. In Naples there would be pizza.

Rafael Esposito, the chef at Pizzeria Barandi, was tapped to make a pizza for the queen. He decided the pizza needed to reflect the colors of the Italian flag, basil for green, mozzarella for white, and tomato for red. And he would name the pizza after her majesty, the Margharita Pizza, for Queen Margharita.

Her love of the dish renewed the world’s interest in pizza and began the term for Naples. But the toll of cholera forced many to flee to places like the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States. A few of those who fled were for Filippo Meloni, Gennaro Lombardi, Maria Puzo, Anna and Francesco Pennino, Gabrielle and Teresa Capone, and Assunta Cantisano. These six Neopolitans would help shape the 20th century.

Filippo Meloni was a dough maker in Naples before departing for the U.S. Unmarried him without children, Filippo settled in the little Italy part of Manhattan, where he turned to what he did best, making dough. In 1903, he opened the first pizzeria in America, and then opened three more. But a bit overwhelmed, he sold the first 192 grand-street location to another Naples immigrant, Gennaro Lombardi.

It isn’t known if Gennaro Lombardi is related to the 1790 cookbook Chef Lombardi, but he changed the name of the restaurant to Lombardi’s and is often credited as the father of pizza in the US. Sadly without any kin, Filippo Meloni was buried in an unmarked grave in Queens, leaving Gennaro Lombardi to carry the torch.

Anna and Francesco Pennino left Naples in 1899, settling in New York City. Drawn to theater of music, Francesco both composed music and owned a theater. With a high population of Italian immigrants, Francesco imported Italian films and they lived above his theater in an apartment with their daughter, Italia.

When Italia was 22, she fell in love with and married her best friend Carmine. Like her father, Carmine was a music composer, a floutist and had studied at Julliard. He would get a job with the Detroit Symphony, moving Italia there, where they had three kids, August, Francis, and Talia.

Their son Francis contracted polio as a child and was bedridden for long periods of time, during which he created puppet shows and enacted full movies like “Streetcar of Desire”. It is here that he developed a love of theater that one day led him to UCLA Film School.

In a similar story, Maria and Antonio Puzo left Naples just after the turn of the century. With their two children, they settled in the Hills Kitchen area of New York City and had ten more children living largely in public housing project. Antonio spent his days as a railroad track worker, but he was plagued with mental illness. Sadly, his condition devolved into schizophrenia, and he was institutionalized, when their son Mario was only twelve years old.

Antonio and Maria were both illiterate, that didn’t stop Mario from excelling in school. He was told by two of his teachers that his compositions were good enough to be published. Mario got a job in the railroad industry, as had his father. Working as a switch attendant, he used the time to read everything in the 11th Street Public Library on Drama.

Destined for College, World War II had different plans for boys his age. Mario joined the Air Force and was sent to Germany, where he was assigned to the government of captured towns and France. He spent all his time in France and Germany, never making it to his parents’ homeland of Italy.

Italy was an anomaly for the US and World War II, with so many Italian Americans in the US military, and with a country full of Catholics, Italy was a tough target, especially Rome. Rome was over 2,500 years old, which caused many Americans to vehemently oppose the bombing.

The British had a similar quandary, but one man was quite vocal in his support. H.G. Wells. Since Italy took part in the German blitz bombing of Europe, H.G. Wells said, “Give him hell.”

Naples had its own role in World War II. Even though the Allies felt it necessary to bomb the munitions plant in nearby Palooza, they did try to avoid civilian targets in Naples. While it seemed like the Neapolitan citizens would have been furious with the Allies and the bombings, it wasn’t until the Germans got close that their true colors were exposed.

Prior to the German occupation, on September 23, 1943, announcements were made that young men were to step forward as laborers and those living within 30 meters of the coastline were to evacuate. No Neapollitan was going to be told what to do or how to live that day.

So with zero planning, the citizenry grabbed their knives, pitchforks, shovels, guns, and broom handles in defiance. And then using the myriad of underground passageways, they continually surprise attack the Germans for four days, before turning back their almighty and powerful armored tank division, allowing the Allies to liberate the city on October 1, 1943. This event has been named “The Four Days of Naples” and has been celebrated every year.

With the Germans expelled, the Allied forces set up an air base at Palm Cape Field to help command and control southern Europe. Unfortunately, eleven months later, in one fell swoop, 88 aircraft were destroyed. The base was permanently disabled, and nearby villages were sacked. But not by the Germans.

In 1944, Mount Vesuvius erupted again, with no regard to the war or Naples. It is said that America’s exploits in Italy are the reason pizza became popular after World War II. But the truth is, only 15% of American soldiers were ever in Italy and only a fraction of those experienced pizza.

The real story about pizza in America is the changing face of America itself after the war. Italian Americans were quickly becoming some of America’s most famous people. Joe DiMaggio and Yogi Berra, fresh from World War II, were dominating baseball. Frank Sinatra and Enrique Caruso were selling millions of albums.

In Enrique Caruso’s most famous song, O Solo Mio, had actually been written by a poet from Naples, and was sung in the Napoleon dialect. A song that brought pizza to the forefront of America’s consciousness was number two on the Billboard charts by Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis. Perhaps you know it from the lyrics.

“In Napoli, where love is king,

when boy meets girl, hears what they say.

When the moon hits your eye,

like a big pizza pie. That’s amoré.”

And pizza was featured in America’s most popular shows. Jackie Gleason’s character Ralph Crandon was forced to sit and watch his friend Ed Norton eat pizza, while his wife made him eat a salad, on the Honeymooners.

And Lucy found herself working in a pizza restaurant to help their Italian friend in an episode of I Love Lucy.

In 1954, up and coming actress Sophia Loren starred as a Naples Pizza vendor, a job she actually had, and a movie for up-and-coming movie producer, Dino de Laurentis.

But America’s fascination with Italian culture wouldn’t peak until 1969.

Remember Mario, who wanted to go to college for literature, but was enlisted in the Air Force and sent to Germany? Well, upon his return from World War II, he did graduate from City College of New York and wrote a couple of books.

Then in 1969, he published a book that sat on the New York Times Bestseller list for 67 weeks. That book was about the life of organized crime in America. It was called The Godfather, and its author, Mario Puzo.

But that brings us back to the beginning of our story and the list of the six people from Naples who changed the 20th century. Gabrielle and Teresa Capone left Naples at the turn of the century for America. After a couple of short moves, they settled in Chicago, where they raised nine children.

One of them, named after Queen Margharita’s granddaughter, Mafalda. At the age of 29, Mafalda opened a deli on Chicago’s south side, called Fox’s Beverly Pub. It became known for killer Italian sandwiches and Neopolitan Lasagna.

The Capones weren’t exactly famous for their deli, however they were heavily involved in the food and beverage of business. When prohibition was enacted, they got involved in making, selling and distributing black market alcohol. Their middle child Albert became part of Chicago’s organized crime scene, and like Michael Corleone in The Godfather, he became notorious, and most people know him, not as Albert Capone, but as mobster, Al Capone.

here is a story from the Capone family lore about Mafalda and her Fox’s Beverly Pub. It is said that one day a customer came in and requested the recipe for her tomato sauce in the lasagna, and Mafalda gave it to them. The Capones believe that this customer took the recipe and turned it into the famous Ragu Sauce you see in stores.

But that’s only true in Capone family history.

Because Assunta Cantisano is our fifth influential person to leave Naples at the turn of the century. She and her husband settled in Rochester, New York. They had been farmers in Naples and immediately started growing tomatoes in Rochester. To help make ends meet, they started making tomato sauce and selling it from their front porch while their son paddled to local restaurants.

When their sales outgrew their kitchen, they opened their first factory and started selling their Italian Ragu Sauce in jars. Their sales went from 150,000 in 1953 to 22 million in 1969 when they sold to Chesebrough-Pond who grew the Ragu brand to $200 million annually.

Ragu commercials tapped into the Pro Italian sentiment by using the tagline, “That’s Italian.”

Remember Italian Carmine and their son Francis who contracted polio? After UCLA Film School, Francis would go on to make many movies, and the one to make him famous was a World War II biopic about General George S. Patton, titled Patton.

Yes, Francis’s parents are Italia and Carmine Coppola, and they gave Francis a middle name based on their hometown of Detroit. You know him as Francis Ford Coppola, and his movie Patton made him a sought-after director.

Paramount had him on their radar when they had just purchased the movie rights to Mario Puzo’s Godfather, and were looking for an Italian American to direct it. Francis Ford Coppola accepted the job, and not only won the Academy Awards for it, but also made a movie many considered the greatest movie of all time.

In true family style, Francis’ father helped write the score and songs, and Mother played an important non-speaking role in the film. Known for her cooking, Francis’ mother, Italia Coppola, would publish a cookbook called “Mama Coppola’s Pasta Book”, and Francis would create an entire line of foods based on his “Mama-rell’s Cooking”.

The Godfather also inspired an Omaha entrepreneur to open a pizza restaurant of the same name. That restaurant would later be purchased by Willie Theisen and turned into one of America’s biggest chains, Godfathers. But Omaha’s Godfathers wasn’t the first national pizza chain.

That title belongs to Pizzaria Uno, of Al Capones, Chicago. Shaky’s, Pizza Hut, Little Caesars, and Dominoes also began to populate the suburbs of America. Today, Italian food is ubiquitous with American food. Pizza restaurants, frozen pizza, and fancy restaurant specials can be found in every city in America.

The food of peasants has become the food of kings.

Even though Naples was hit with seven different cholera epidemics in the 20th century, pizza wouldn’t be stopped until the COVID epidemic of 2020. On March 13, 2020, the sale of pizza was banned in Naples, and the public was mandated to stay home. And for 29 days, no pizza would be had until a miracle happened, and the government of Naples passed a law allowing pizza home delivery for the first time.

Over 20,000 pizzas were delivered in one day.

And thus continues the saga of Pizza.

CUTTING ROOM FLOOR

To hear all the stories that hit the cutting room floor, you have to listen to the episode.

ABOUT THE SHOW

Let us tell you the story of the 20th Century, by tracing each event back to the original decisions that shaped it. You’ll quickly find out that everybody and everything is connected. If you thought you understood the 20th Century, you’re in for a treat.

Tracing the Path is inspired by storytellers like Paul Harvey, Charles Kuralt, and Andy Rooney.

INTERCONNECTED EPISODES

|

The Official Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon It just so happens Tracing the Path is friends with the creator of the Six Degrees, and he’s only 1 degree away. |

|

Evolving Civil War Sutlers into the Bob Hope’s USO Many factors went into the success of the USO. It wasn’t necessarily just big hearted celebrities |

|

Who Started the Outer Space Race? Elon Musk isn’t the first person to have his eyes set on Mars. |

SEE THE BIBLIOGRAPHY

SUBSCRIBE AND LISTEN (FOR FREE!)

RATINGS & REVIEWS

If you enjoy this podcast, please give it a rating and review.Positive ratings and reviews help bring Tracing The Path to the attention of other history lovers who may not be aware of our show.