TRACING THE PATH PODCAST

The Fairy Tale of Sixto Rodriquez

This episode traces the unexpected global impact of bootleg music recordings, specifically highlighting how two such albums intertwined with the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa. The story explains that early copyright laws did not cover recorded music, making bootlegs a significant, albeit initially unregulated, form of music distribution.

It then narrates the parallel stories of Sixto Rodriguez, an American musician whose largely unnoticed albums became a powerful voice for anti-apartheid sentiment in South Africa through bootleg circulation. And Lady Smith-Black Mambazo, a South African group whose traditional “Skatamir” music found international fame after Paul Simon heard a bootleg recording. Ultimately, the piece demonstrates how these musical connections, sparked by the unconventional spread of bootleg albums, played a role in challenging and ultimately dismantling apartheid, showcasing the profound and unforeseen influence of art across geographical and political divides.

Audio Hour:

If you run an activity group, classroom or “audio book club”, click here for more information on using Tracing The Path.

Throughout the episodes, every tune is somehow related to the topic. In the Twinkies episode, for instance, the discussion of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops Baseball team concludes with “Take Me Out To the Ballgame”.

How many do you recognize? And harder, how many can you name?

The Other Role of Ghandi

In 1969, a Bob Dylan album was released, called “The Great White Wonder”, except Bob Dylan didn’t put it out. It was the first successful bootleg. And at that time, there was no law forbidding it.

The idea of recording someone playing music and then selling it was not against copyright law. The law covered only visible expressions of creative effort like sheet music; recording music in the air was not copyrightable. While some have argued bootleg recordings harm artists, others have shown that bootlegs increase an artist’s popularity by introducing them to thousands of new fans.

And two bootlegs in particular change the world forever.

Our story begins with Mahandas Gandhi. Gandhi was born in 1869 in the coastal town of Porbander, India. As custom would have it, Gandhi only lived to the age of 13 before an arranged marriage was thrust on him, to which they would have a child together. And at 17, Gandhi left India to study law in London.

A few years later, on his return to India, he was approached by an international merchant who was looking for an attorney. He needed a lawyer in South Africa, one of Indian heritage. The pay was good, and South Africa was part of the British Commonwealth, so Gandhi agreed and took his family there.

Immediately upon arriving in South Africa, Gandhi faced discrimination, a feeling he hadn’t felt before. He was not allowed to sit with European passengers on the train, but instead was made to sit on the floor. One time he was pushed into the street for walking too close to a building. And in a small moment of defiance, he refused to give up a seat on the train for white passengers.

His refusal got him thrown off the train.

On several occasions, he thought he should leave and go back to India, but his heart made him stay and fight for the rights of other Indians. In 1894, he helped found the National Indian Congress, with hopes of one day unifying the Indian people. When the South African government tried to restrict Indians even more, he peacefully opposed it and negotiated a compromise with the government on voting rights and on taxation.

In 1913, the South African government took another big leap, passing a land act, which marked the beginning of territorial segregation in South Africa. And in 1914, martial law was declared, and life in India seemed like a better place for Gandhi.

And so he and his family left.

Life for Indians and Native Africans in South Africa got even worse after that. Soon everyone had to register their race with the government. Mixed marriages were outlawed and 80% of the land, through more land laws, was set aside for the white minority. Each race was forced to move into separate communities to make sure they would never join together in opposition.

Over 3.5 million people removed into poverty-ridden establishments.

In 1927, the government passed the Hostility Act that forbade anything that could create hostility between the races, which meant news, media, music, and the arts were carefully centered. And the government made sure no news about apartheid left the country, and no news about the prosperity of the rest of the world entered the country.

That is, until 1946, when South Africa passed the law, making it legal to discriminate against Asians and Indians. Far away in India, when Gandhi heard about the new law, through friends, he acted immediately. It had been thirty years since living there, but wrong was wrong. He appealed to the President of India to take the case to the United Nations.

The UN was only one year old at the time, but it did have the attention of the world. It would be the first request of the UN to crack down on a member country. The only problem was the UN Charter. It specifically stated the UN wouldn’t get involved in a country’s domestic issues, a clause inserted and pushed for by South Africa.

But the Indian president felt the same as Gandhi.

The Indians in South Africa were being very poorly mistreated, and so the motion was brought to the UN. And despite South Africa, the United States and the UK, denouncing the motion, India got two-thirds of the UN to agree, and the resolution passed. It would mark the very first time the International Community would speak up about apartheid.

The Arrival of Apartheid

The rebuke was only words, however, and nothing changed.

In fact, the following year, a new president would be elected in South Africa, and his platform was apartheid. Sadly, that same year, 1948, Gandhi was assassinated in India.

Not everyone shared his views. South Africa’s apartheid atrocity would go largely unnoticed for twelve more years. Until the South African police opened fire on a peaceful anti-apartheid rally in the town of Sharpeville, when the word got out, the world noticed.

In 1961, South Africa was forced to withdraw from the British Commonwealth. World Cup Soccer banned the country. In 1964, the Olympics banned South Africa. At a 1973, the UN voted again, imposing a mandatory embargo on exports to South Africa.

The culture of apartheid severely impacted the musicians inside South Africa. Not only were they isolated from the rest of the world, but they were also pushed into poverty-ridden communities without great access to exposure.

A land act in the 1950s had moved all the Zulu men off their land and into single sex hostels where they worked in the mines isolated from their families. To escape their situation, they turned to traditional singing and dancing. But the barracks they lived in with people living above and below them, didn’t allow the traditional Zulu warrior dances marked by loud voices in rhythmic stomping.

So they had to invent something new. A new type of music, they called “Isicathamiya“, meaning “tiptoe,” and as soothing as its “tiptoe” name implied, which brings us to the first hero in our story.

Joseph Shabalala

Joseph Shabalala was only a child when he started working. He’d grown up thinking he might be a doctor someday, but when his father died, he had five brothers he had to take care of, all at the age of twelve.

Without a lot of time for normal kid activities, he fell in love with the tiptoe of Isicathamiya singing and dancing. So much so, he formed a group, which he named after his hometown of LadySmith. He wanted his group to be the best in the world, so he chose the name Mambazo, meaning “ax,” because he was going to cut a path forward.

Lady Smith Black Mombazo.

Every Thursday night there would be competitions, and his group would almost always win. There were other groups as well, like the Boyo boys, that were just as good. But Joseph pushed his group, as he believed their voices would one day take them to the best stages of the world. They won so much, they were eventually banned from competing altogether, and it could only perform as exhibitionists.

In 1972, they got their first break, a random performance on Zulu Radio caught the attention of a record company, and they got to cut their first album, which sold 40,000 copies, all inside South Africa. The hostility act of apartheid and world isolation still left them without a global voice.

Which takes which takes us across the Atlantic Ocean to the United States, where we meet the next hero of our story.

The Miracle of Sixto Rodriguez

Life for the minority races in North America wasn’t much better in the 40s and 50s. Peasants in Mexico were making less than 50 cents a day, with little hope the future would change that. Hundreds of thousands of Mexicans emigrated to the U.S. by crossing the Rio Grande River.

Most found work on farms across the Midwest, and places like Detroit that were bustling with industrial jobs were also attractive. The Rodriguez family were one of those Mexican immigrant families in Detroit. They had six children, the sixth one aptly named “Sixto”.

Sixto grew up in the racial tensions of the Detroit Ghettos. He had an acute awareness of the alienation and marginalization that Mexican American immigrants felt. And he was an academic who loved talking about the issues of the day, debating sides and coming up with societal solutions to problems. He was even able to get himself a scholarship to Wayne State University, where he earned a bachelor’s in philosophy.

But music was his heart. He’d play in bars, on streets, and in restaurants all over Detroit. Unlike Lady Smith-Black Mombazzo, he got his big break one day when a couple record producers heard him play.

Dennis Coffee and Mike Theodore. Dennis was a session guitarist for Del Shannon, the temptations, and Edwin Star, and both of them were producers at Sussex Records. To them, Sixto sounded a lot like Bob Dylan, who was popular at the time, and thought his songs would play well on the radio.

So in 1970, Sixto Rodriguez cut his first album, Cold Fact, with Sussex Records. But it got little attraction and fewer sales. A year later, they decided to cut a second album, coming from reality, to help boost the first. But again, few sales were made. But then something amazing happened.

One of Sixto’s fans took a trip to South Africa and brought the album with them. Unbeknownst to the rest of the world, the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa was growing. But because of the hostility laws, they didn’t yet have a musical icon who put their feelings into words, until… Sixto though.

Even though his lyrics were based in him being a Mexican in Detroit, he was the first musician South African’s heard talking about standing up against your oppressor. It is said that his song, “The Anti-Establishment Blues” is the first song to give people permission to protest against society, to be angry with society.

And from that, the first wave of anti-apartheid musicians in South Africa began to pop up.

From Music to Freedom

Sixto’s album was copied and copied and copied. South African music producers even got it into record stores. But once they could, the government ordered some of the songs be scratched from the album and made unplayable, which made the bootleg copies even more sought after.

By the mid-1970s, it is said that every middle-class household with a turntable likely had three albums, Abbey Road by the Beatles, Bridge Over Troubled Water by Simon and Garfunkle, and Cold Fact by Sixto Rodriguez.

Sixto was more popular than Elvis, and perhaps the most famous musician in South Africa.

Outside the country, the apartheid movement was heating up as well. In 1971, Coca-Cola had a hit song and commercial called “The Hilltop,” featuring the song “I’d like to teach the world to sing”.

When they brought the multi-racial commercial to South African TV, they were asked to cut another version with only white children. Coca-Cola refused to make the change. So Coca-Cola pulled out of South Africa. In 1980, the UN passed Resolution 35206, which stated that “all states prevent all cultural exchanges without Africa.”

In 1979, tennis great Arthur Ash had been banned from going to South Africa to play in a tennis tournament. So in 1983, he and Harry Belafonte started a group called Artists and Athletes against South Africa, bringing more exposure to the situation. But for Lady Smith-Black Mumbazo, all these protests had an unforeseen consequence.

While no one was coming to South Africa, it was a making it impossible for them to get exposure beyond their borders, which brings us to the final hero of this story.

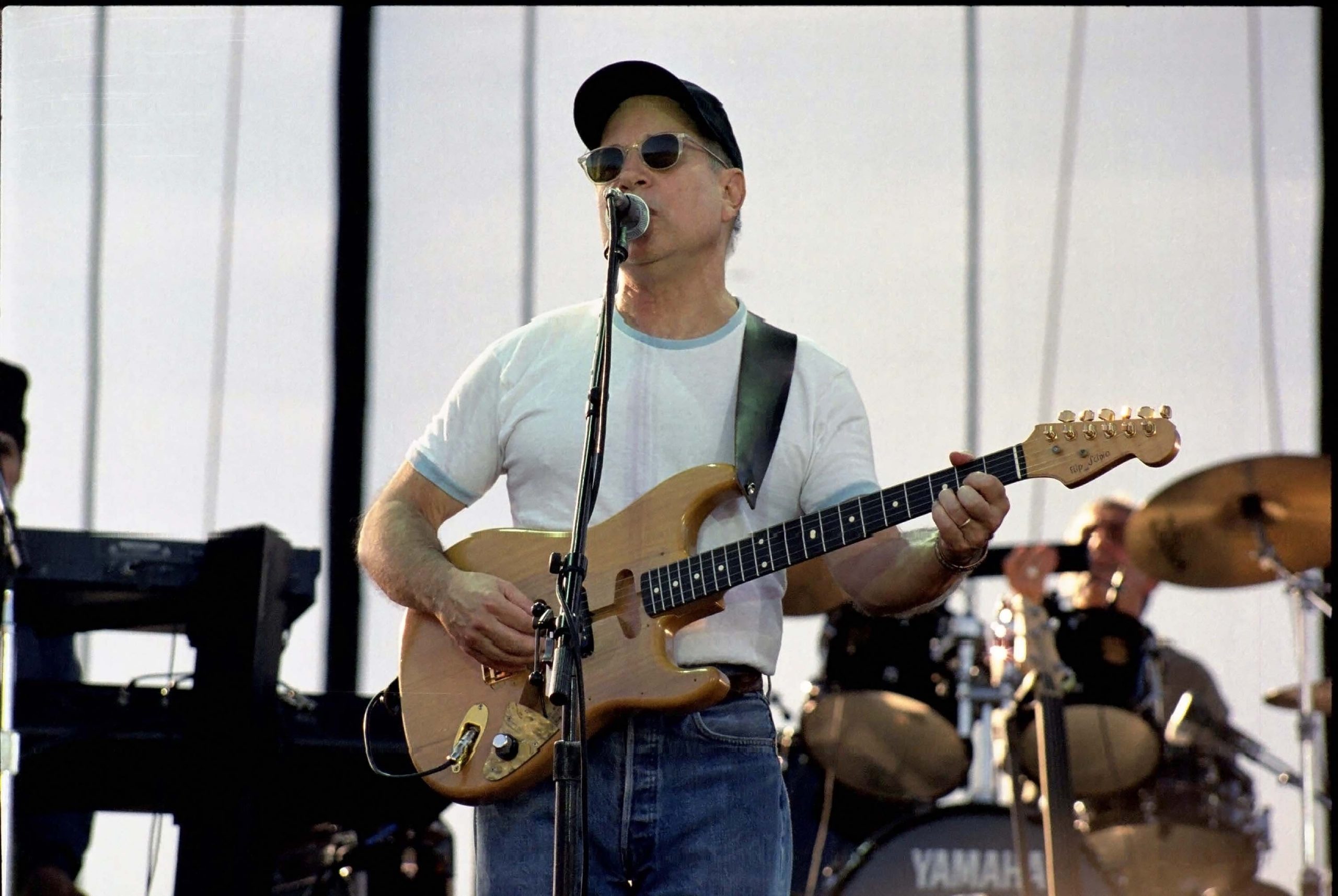

Paul Simon

In 1984, the producer of the hit TV show Saturday Night Live, Lauren Michaels, tried his hand at creating a new show, amazingly called “The New Show”. But after only a few months of episodes, the show was canceled.

Heidi Berg, the musical director of the show, was looking for new work and possibly recording an album of her own. So she headed down the hall to an office of a friend, Paul Simon, half the duo that created Bridge Over Troubled Water. She and Paul hit it off and began looking at ideas for an album for her.

One day, Heidi brought Paul a cassette tape of song she thought had a great sound. The tape was a bootleg recording of the Boyo boys from South Africa. Paul Simon took the tape but then took five days before Paul Simon put the cassette in the tape player and press play. But once he did, it didn’t come out. He was hooked. Because of apartheid, he’d never heard the type of music before, and found it had reinvigorated something inside him.

He wanted desperately to know more about this group. S

outh Africa was a mess, however, with all the boycotts. Not knowing what to do, he called Harry Barlefonte to get his opinion. Should he go to South Africa and find this group? Harry told him it was a good idea to go to South Africa to see if he could meet with these singers. Since it was not to put on a concert which would have been given credibility to the South African government, it would be a good thing for the singers themselves, being one of the most famous music artists of the time.

It wasn’t hard for him to procure a recording studio and appointments to hear nine of South Africa’s finest groups. One of the people who got the request to come to the studio was Joseph Shabalala and Lady Smith-Black Mumbazo.

Joseph knew it was a meeting not to be missed because Paul Simon’s music was currently playing on the radio. For ten days, Paul worked with artists, learning the beats and rhythms of their music, and figuring out how to work on something together. The album he would produce with them, he titled “Graceland,” and it wouldn’t come without controversy as it was produced during the cultural boycott.

But its significance would transcend the controversy. 16 million people worldwide would buy the album. The vision Joseph Shabalala had for the group came true. Lady Smith would go on to perform on the finest stages of the world, for the Queen of England, for the Pope, and for the President of the United States.

Three years later, in 1989, F.W. DeClerK became President of South Africa, and released the country’s most prominent anti-apartheid voice, Nelson Mandela. Together they would dismantle apartheid’s political structure and would go on to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

And at the invitation of Nelson Mandela himself, Paul Simon and Lady Smith Black Mombazo played sold-out concerts in Johannesburg in celebration of the change. But neither Paul nor Lady Smith would ever reach the popularity of Sixto Rodriguez.

In 1991, Cold Fact was released on CD for the first time, sparking interest in two South American journalists trying to learn more about Sixto. Rumors had existed for years that Sixto had died on stage during a concert, but had he really? So in 1997 at the dawn of the internet, Stephen Seagriman, the owner of the Cape Town Record Store Mabu Vinyl, created a website called “The Great Rodriguez Hunt”.

He was interested in learning more about Sixto from anyone who knew him. Prior to the internet, getting information from other countries wasn’t easy, as phone calls were expensive and writing letters took a long time. But with the internet, it wasn’t long before Eva Alicia Rodriguez added a comment on the website.

She wrote, “Rodriguez is my father. Contact me.” Only a few days later, Steven Seagerman got a phone call from Sixto Rodriguez himself. In that call he learned that after Sixto’s two failed albums in 1971, Sixto quit music and got a construction job in Detroit. He’d been living in a derelict house, Sixto bought from the city of Detroit and largely living paycheck to paycheck, working construction jobs.

But for Sixto, he learned the impossible. He learned an album had been brought to South Africa and copied so many times, he was more popular than Elvis and the Beatles. His record company Sussex had closed up shop shortly after he quit, and he had never been contacted about album royalties, the sale to South African record company, or anything else.

He knew nothing.

Sixto was very unsure, but wanted to see it for himself, and agreed to come to South Africa, where he performed four sold-out performances to thousands of fans singing along to every song.

The dream was real.

It is a fairy tale that will likely never happen again, amazing that it even happened once.

Since then, Sixto has performed around the world on stages that he only dreamed of as a little boy.

CUTTING ROOM FLOOR

To hear all the stories that hit the cutting room floor, you have to listen to the episode.

ABOUT THE SHOW

Let us tell you the story of the 20th Century, by tracing each event back to the original decisions that shaped it. You’ll quickly find out that everybody and everything is connected. If you thought you understood the 20th Century, you’re in for a treat.

Tracing the Path is inspired by storytellers like Paul Harvey, Charles Kuralt, and Andy Rooney.

INTERCONNECTED EPISODES

|

|

The Cheesy Results of WWII It all started in Wisconsin but turned quickly into a nationwide program |

|

How many times has Coca-Cola Changed the Recipe? Coke Classic was one, right? But did they really change it back to the original? |

|

187 Years Behind Martin Luther Kind’s Dream We all learn about the “I Have a Dream” speech, but few know where it comes from. |

|

484 Year Documentary of Muscle Shoals It wasn’t just the music that made it famous? Can you hear Helen Keller? Or see Henry Ford? |

|

When 26 Million Teens Waited for the Beatles The phenomenon that occurred when the Beatles were live on the Ed Sullivan show could have been predicted. . . |

|

The History and Impact of McCann Erickson You’ll be amazed at how many things in our world come back to McCann. |

|

How the Transistor and Pirate Radio Created Rock-n-Roll Back to the Future isn’t a “origin of rock-n-roll movie, but then again it really is. Except it doesn’t mention Radio Caroline. |

SEE THE BIBLIOGRAPHY

SUBSCRIBE AND LISTEN (FOR FREE!)

RATINGS & REVIEWS

If you enjoy this podcast, please give it a rating and review.Positive ratings and reviews help bring Tracing The Path to the attention of other history lovers who may not be aware of our show.