TRACING THE PATH PODCAST

This episode of “Tracing the Path” explores the historical efforts to support and entertain soldiers, particularly focusing on the challenges of maintaining morale and providing structure during wartime.

It begins with the story of Milton Bradley, whose “The Checkered Game of Life” provided comfort to Civil War soldiers, and then highlights the origins and vital role of the YMCA in offering a “piece of home” to young men.

The narrative then expands to World War I and the comprehensive efforts of the USO in World War II, emphasizing figures like Raymond B. Fosdick and Thomas Dewey, and ultimately culminating in the unparalleled dedication of Bob Hope, who spent decades performing for troops worldwide. The podcast underscores the profound impact these initiatives had on soldiers’ well-being and the surprising contributions of various individuals and organizations to this enduring cause.

Audio Hour:

If you run an activity group, classroom or “audio book club”, click here for more information on using Tracing The Path.

Throughout the episodes, every tune is somehow related to the topic. In the Twinkies episode, for instance, the discussion of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops Baseball team concludes with “Take Me Out To the Ballgame”.

How many do you recognize? And harder, how many can you name?

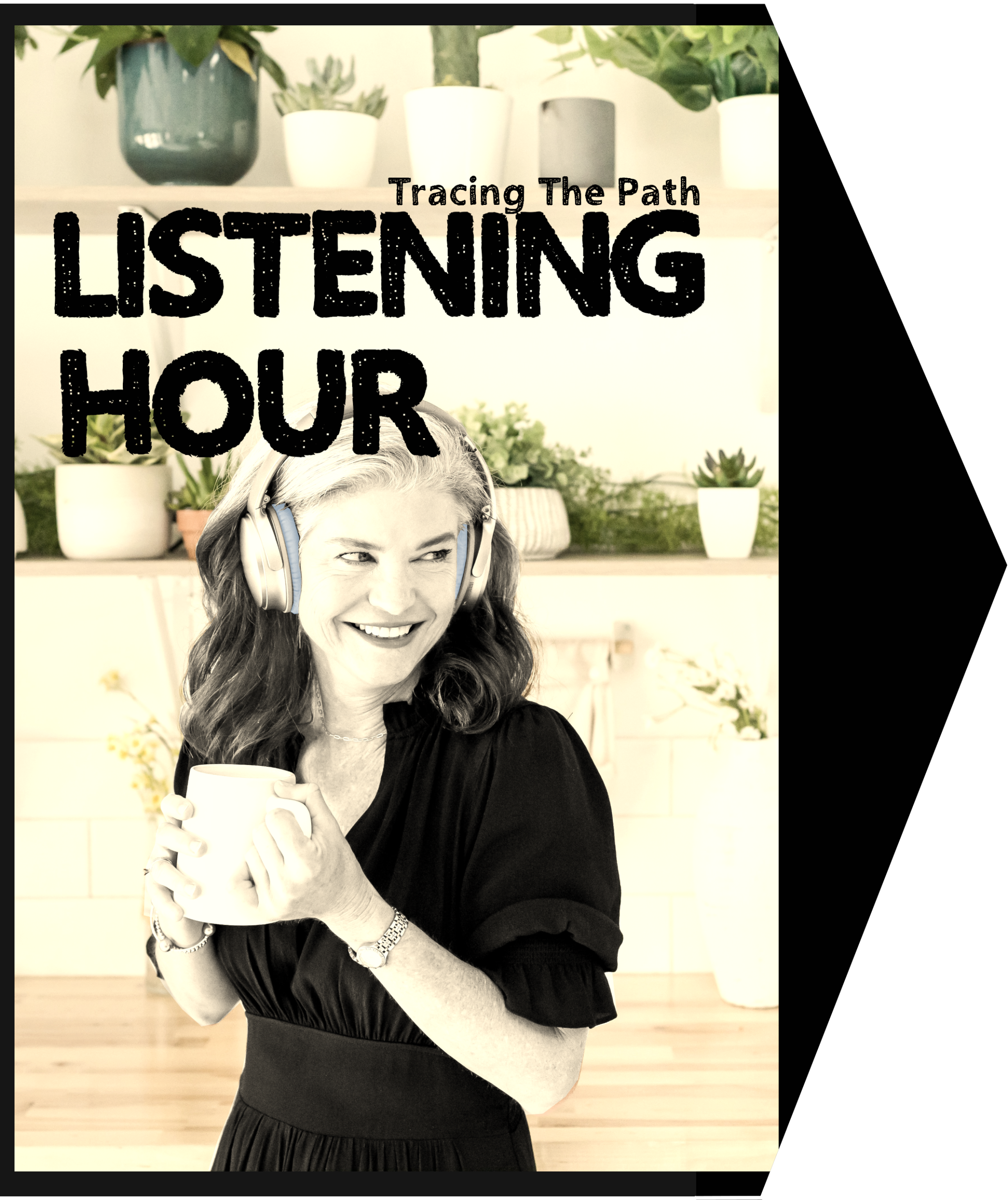

Milton Bradley’s Game

There is something special about the cocoon you live in growing up.

Watching TV in the living room, grilling burgers and hot dogs in the backyard. Taking that structure away has good and bad results. Sometimes leaving home early gives you the drive and determination it gave Oprah Winfrey. Other times, the lack of structure creates serious problems.

But with the right people, you end up with hope.

Our story begins in 1836 with a name you know and love, Milton Bradley. Milton was born in Maine, but throughout childhood and high school, he had lived in Springfield. Massachusetts before moving himself to Providence, Rhode Island to learn lithography.

Courier and Ives, a New York company, had made lithographs famous. They had been making them since 1835, selling images of news events, life, and views of popular culture.

Milton had similar early success after printing an image of a littleknown Republican presidential candidate named Abraham Lincoln. His success, however, was short-lived. because Lincoln grew out his beard, making Milton’s print no longer accurate.

Milton then struggled to figure out how to use his lithography skills, and that’s when he was invited to a friend’s house to play an English board game. The experience gave him the desire to make a unique, purely American board game.

He wanted a game that mirrored the culture.

It would start players at infancy and move them along a track to old age, making decisions along the way. Milton would build it with a spinner instead of dice to distance it from gambling. He called it The Checkered Game of Life.

By 1861, he had sold over 45,000 copies, and he was sure board games were his future.

Also, in 1861, when the Civil War broke out, he had to temporarily stop making them, but instead tried his hand at making weapons. However, when he stumbled upon some soldiers who visibly had nothing to do while awaiting orders to report to war, he wanted to help them.

He wanted to give them a piece of home.

So, he started producing small games for them. Those small games, including chess, checkers, backgammon, dominoes, and the Checkered Game of Life, are now considered the first travel games.

He sold them to soldiers for only a dollar a piece.

But he wasn’t the first to have a heart for the young men who left home to become soldiers.

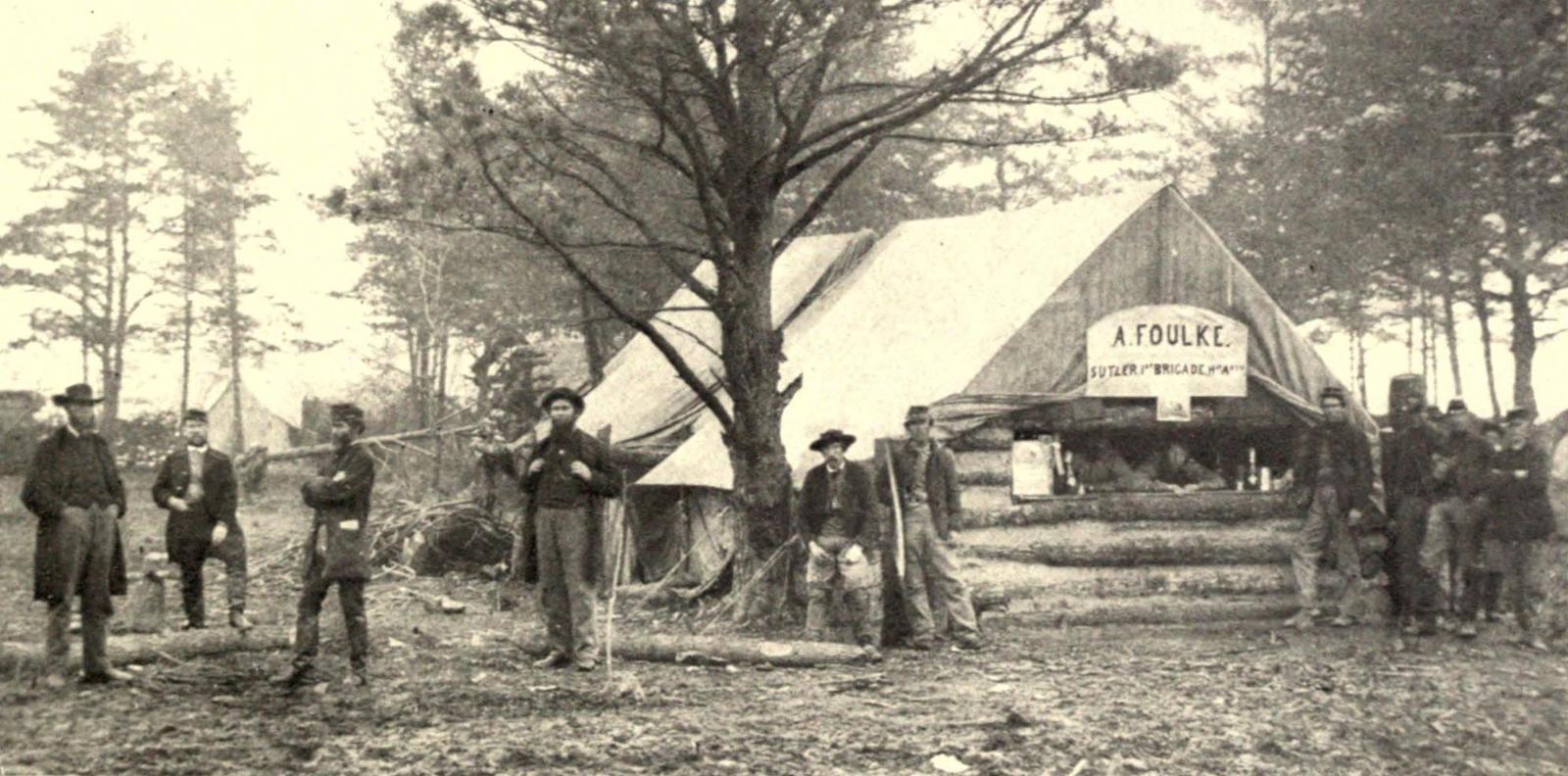

The Civil War Sutler

It was 20 years earlier in London, a farm worker saw that while the industrial revolution moved people from the countryside to the city, there really was wasn’t anything for the young men to do but drink alcohol and visit brothels.

He wanted something better for them, a way to escape the harsh realities of the streets.

So in 1841, he and 11 friends got together and started a group called the YMCA.

By 1851, there were 24 YMCA facilities in the United Kingdom and one in Boston in the New World. Despite it being the first social group to invite people from all religions, it was instantly popular.

By 1861, there were YMCA’s all over the United States. The Civil War would not only cause a halt to growth, but it would reduce the YMCA’s membership by a third because of all of the men who entered the war.

Civil War soldiers on both sides weren’t provided very much. Both sides paid their soldiers $11 a month. And the soldiers were given rations, uniforms, weapons, ammo, blankets, and tents. But President Lincoln knew that wasn’t going to be enough.

In fact, the soldiers weren’t even given soap.

So Lincoln had a conference with the YMCA leadership. 15 of the YMCA organizations joined forces together to form the US Christian Commission, where they then served as surgeons, nurses, and chaplains.

During the war, Lincoln also helped create a full-scale recruitment of volunteers who distributed medical supplies, food, clothing, and even taught soldiers to read and write. But the soldiers needed more than the basics.

For the most part, if they weren’t in a town, there was no way to get upgrades. The only real option was the private sutlers, who were considered a necessary evil. Sutlers were private merchants that set up shop within the troops camps after getting appointed by the regimental commanders.

And since they had no competition, they charged whatever they wanted for all the stuff they sold in their store.

The only upside was that the sutler’s profits were taxed by the unit they were serving, the money of which the unit used to buy music and books for the soldiers, a little taste of home.

Which brings us to the first hero of our story.

Raymond Fosdick was born in 1883 in Buffalo, New York to a working class family. But through academics, he rose in the ranks and at the age of 22, academics got him a bachelor’s degree from Princeton and by 1908, a law degree from New York City.

It was at Princeton that Raymond became acquainted with one of his professors, Woodrow Wilson. Wilson used his contacts to help Raymond to get a job as a public investigator for the city of New York.

While an investigator, he was assigned the task of solving prostitution and sex trafficking. The problem was big enough, John D. Rockefeller got involved and had Fosdick travel to Europe to study how their police handled alcohol, prostitution, and the morally corrupt activities.

For each of these investigations, Fosdick would issue a report, after several of which he started to become famous.

One of his reports caught the attention of Newton Baylor, the United States Secretary of War, who then appointed Fosdick as chairman of the Commission of Training Camp Activities. Fosdick’s mission then was to investigate the conditions at the 1916 Mexican border conflict.

He was to investigate the social hygiene and military training camps linked to prostitution and morally corrupt behavior due to alcohol.

Fosick’s recommendation was to ban alcohol and prostitution, clean up the troop camps, and provide recreation activities like sports. He then went on to do the same thing in France for the War Department, working alongside General John J. Persjing.

General Pershing appreciated Fosdick’s methodology as he had his hands full being leader of the American Expeditionary Forces.

He was definitely too busy to manage the off duty soldiers.

But unlike the Civil War, where sutlers and the YMCA were the only outside help for the soldiers, World War I brought out the YMCA, the Knights of Columbus, the Salvation Army, the Jewish Welfare Board, the American Red Cross, and the American Library Association.

28 organizations in all attempted to individually help.

The YMCA was the main provider. They actually provided 26,000 paid workers and 35,000 volunteers, helping to manage the mail, helping soldiers write home, providing morale boosters, and they even built some skating rinks. The YMCA did it all through contributions.

Their ads featured a young YMCA person giving coffee to a soldier with the slogan “For your boy.” The slogan generated thousands and thousands of contributions.

And 5,145 women served through the YMCA supporting soldiers in France. One of those women was Teddy Roosevelt’s daughter-in-law, Edith. Which brings us to the next hero of our story, Thomas Dewey.

Thomas Dewey’s and the History of the USO

Thomas Dewey had a similar story to Raymond Fosdick.

Thomas was born in 1902 in Michigan and grew up to get his Bachelors in 1923 and his law degree in 1925 from Colombia. He too went to work for the government in New York City as a prosecutor and DA.

There he lived in Quaker Hill just outside New York City where his neighbors were Edward R. Murrow, Lowell Thomas and Norman Vincent Peele.

Dewey served as governor of New York for 12 years and also as chair of the Republican National Committee. But what made Dewey a significant figure in the 20th century is that he battled mobs, crime, and prostitution.

He was the one that took on Lucky Luciano, Dutch Schultz, and Waxy Gordon.

Not only that, But he had the ethical fortitude to go after criminals even when they were considered the good guys, like Richard Whitney, the New York Stock Exchange president.

Thomas Dewey proved he was willing to fight for what’s right. The period between World War I and World War II, known as the interwar period, was a time of great political instability in the US and abroad.

- Abroad, the Japanese looked as if they were going to attack China at any moment.

- Italy actually invaded Ethiopia.

- And in what many consider to be the beginning of World War II, a civil war raged in Spain, pitting Germany against Russia.

In 1939, it looked like another World War was pending.

And so, in September of 1940, Roosevelt approved a military draft. And very surprising to the military, 1.1 million soldiers got off their living room couch and enlisted, which gave Roosevelt a new problem, housing.

Without declaring war and sending the troops to Europe, where would they temporarily house them all? Roosevelt knew from history that the men could get rowdy when sitting around with nothing to do.

He knew it wouldn’t be long before they turned to immoral activities. So, he needed a solution and called upon the Army Chief of Staff, George C. Marshall.

Marshall had experience with the issue. He had been with the First Division in World War I, and he was an aid to General Pershing. He knew firsthand the troubles Pershing had encountered. So, Marshall put together a team with the most experienced people he knew, including Raymond Fosdick and Joseph Byron.

Byron was the chief of the Army Exchange Services, specifically responsible for the general welfare of the troops. Byron had actually created an army music program under the assumption that music reduced stress, induced smiles, and brought people together.

Because of that, Byron felt the army would be much more effective if the soldiers could truly relax at times.

So, they created a program that would infiltrate music at every level.

The army music program actually had seven rules.

- Every soldier was to know the songs in the Army song book plus 25 more.

- Every squad was issued a pocket instrument.

- Every platoon was issued a barberhop quartet and campfire instrumentalist.

- Every company got a song leader.

- Every battalion would have a dance orchestra.

- Every regiment would get a drum and bugle corps.

- Every division was assigned two well-trained orchestras.

He felt it was vital to the army’s success that at any moment in time they could create the comfort the soldiers usually felt at home.

Along those same lines, President Roosevelt, George C. Marshall, and the team knew morale needed to be a major focus based on the problems the military had encountered in the past.

They wouldn’t be able to eliminate all the morally corrupt temptations, but they could provide positive alternatives.

So on February 4th, 1941, they created the United Service Organization (the USO) to tackle the problem.

In World War I, 28 organizations tried to help, but they were in no way cohesive. The United Service Organization would bring them all together under one roof. And with their help, they were able to transform hundreds of church halls, abandoned buildings, and private residences into USO centers.

So the waiting soldiers had access to recreation and civilian resources.

And they made Thomas Dewey the first head of the USO.

Thomas Dewey went to work immediately. with his six civilian groups to begin fundraising for the operation. Their message was “Donate to keep the soldiers out of the smoke filled juke joints.”

They published an article each month as well, about things like “the venerial diseases they were trying to avoid” and they labeled this as America’s Greatest Threat.

They even made a short movie that could play before the films at the theater called “Mister Gardenia Jones”, starring a little known actor named Ronald Reagan.

The result, Thomas Dewey famously raised 16 million for the cause. But Dewey actually had some help from the Japanese because on December 7th, 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, which created a level of patriotism and support that was unheard of prior to that.

Everyone wanted to donate. Beyond monetary help, the USO got a boost in a very untraditional way. In fact, without this moment in time, the USO may never have become what it did. But to fully understand this moment in time, we have to go back to 1922 and meet a trumpet player named James Patrio.

Glenn Miller in World War II

James Patrio was born in 1892 and grew up in Chicago with a love of playing the trumpet. Turning the love of music into a career, however, wasn’t easy.

So, James took a job with the local musicians union in 1922. He still played in three different orchestras in Chicago, but the union became his career. So much so that he stayed until 1958.

In 1940, he became the president of the American Federation of Musicians. He was an easy candidate to vote for because he’d already proven himself Back in 1937 when he was pushed against the wall.

He led a strike in Chicago standing up for musicians rights.

His platform as president was making sure musicians got royalties for their recorded music.

So shortly after the election, he announced that if a royalty agreement wasn’t reached with the record companies, musicians would go on strike on July 31st, 1942, which no one really they thought would come true.

And then after Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, many thought Patrio’s idea would be forgotten.

But Patrio was serious. And as the date grew closer, the big three record companies, RCA Victor, Colombia, and Decca started to get nervous. Fearing the strike would actually happen, they didn’t begin to take any actions until July 1st.

And instead they decided to stockpile some recordings and wait the musicians out. So during July, they had Tommy Dorsey, Jimmy Dorsey, Bing Crosby, Guy Lombardo, Count Basie, Woody Herman, Judy Garland, Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington, and Glenn Miller all record a last minute album.

When the strike began on July 31st, musicians were not allowed to record any music.

They could perform on radio or live in concert, but nothing recorded with one exception.

The USO asked the American Federation of Musicians Union if they would allow the musicians to record music to be put on V-Disks that would only be sent to the troops and would never be sold. And Patrio agreed.

The USO was now run by Prescott Bush, the father and grandfather of the President Bush’s, because Thomas Dewey had left to run for president.

Prescott Bush saw the strike as another opportunity for the USO if Hollywood’s most famous musicians weren’t allowed to record and thus had extra time. Maybe they’d perform for the troops in the US and abroad.

And since Pearl Harbor was still as fresh as ever, everyone wanted to do their part.

So the troops got support from Sammy Davis Jr., Mel Blanc, Fred Astaire, Cole Porter, Rita Hayworth, Tommy Dorsey, the Andrew Sisters, and so many more.

Glenn Miller, on the other hand, didn’t want to go and play as a visiting musician. He wanted to join the military and play as one of the troops. Glenn had wanted to be a professional musician his entire life.

In fact, by the end of high school, he had played in the town orchestra and in several bands. He even missed his graduation ceremony because he had a gig to play.

After high school, he played on Broadway with Benny Goodman and Jean Krupka. He played with Tommy Dorsey and Bing Crosby. And by 1938, his band had become very popular.

Time magazine said every jukebox in America had two of Glenn Miller’s albums in it.

In 1940, his song “Tuxedo Junction” sold 115,000 copies the first week. And in 1942, he was presented the first ever gold record for “Chattanooga Choo-choo”. But when the strike hit and the war started, Glenn Miller joined the armed forces, forsaking his $20,000 a week pay, which in today’s money was $300,000 a week.

Instead of contributing to the war effort by playing at a USO, he reported to Omaha as a captain in the Army Specialist Corps. He trained for a month at Fort Mead. Then he was assigned to the AAF Southeast Flying Team.

That is where General Byron made him Director of Bands.

He and his orchestra played all over Europe playing with friends like Bing Crosby. But even as the band director, the life of a soldier is perilous. And so it was for Glenn Miller.

On Friday, December 15th, 1944, he boarded a plane from London to Paris, att the time a treacherous flight. That was also the weekend the Battle of the Bold started and due to the “fog of war”, it wasn’t until Monday that it was realized Glenn Miller’s plane didn’t arrive.

Eerily similar to the circumstances surrounding Buddy Holly’s flight in 1969. The plane went down somewhere over the English Channel.

It was the first day the music died, and the world would mourn the loss of its greatest musician.

The strike would last two more years and would become the longest musician strike in history.

For the record companies, their stockpile of new music ran out quickly, and they were forced to play old stuff, songs that had previously gotten lost. One of those songs had been recorded in 1939 by a largely unknown artist at the time, but now that it was being re-released, it made Frank Sinatra a household name.

Another one was the song “As Time Goes By” which had been recorded in 1931, but now was being re-released because it was in the movie Casablanca.

Raising Morale in World War II

At home, women were stepping up in ways they hadn’t been allowed before. The culture of the patriarchal society kept women at home, but Rosie the Riveter and the ladies playing baseball were a necessity.

Congress knew it had to help and so they passed the National Defense Housing Act, which had a very important subsection, child care.

While the men were at war and the women were at work, the government inadvertently pioneered daycare. Money was set aside to pay for facilities and for workers.

In fact, the entire scope of what was necessary in World War II was staggering. The USO alone created 3,000 domestic centers, 300 pre-fabricated wooden clubhouses, and 125 canteens. On the entertainment side alone, they orchestrated 5,400 performances for 85,000 patients in 79 hospitals.

And there were 428,521 shows in 205,000 USO locations overall.

And that’s including even the small shows like the time a group of women traveled by dog sled to Nome, Alaska to sing for four proud soldiers.

Beyond the organizations that came together to create the USO, the army also worked with other companies to benefit the troops.

Coca-Cola was one of them.

The morale that the USO was intent on building, Coca-Cola thought they could help create. The notion that sitting down and sharing a coke made bond stronger. It was what Robert Woodruff, the CEO of Coke, sold the Army.

Woodruff promised the government that every Coke would be available to GIs for only 5 cents a bottle. General Eisenhower was very much behind the Coke partnership and asked that Coke build enough bottling plants to provide 3 million bottles every 2 weeks, exempting them from the sugar quotas.

So Coke built 64 bottling plants near military bases so they could sell five cent cokes, ultimately losing $83.2 million in revenue.

But it solidified Coke’s importance and provided thousands of jobs to the sleepy towns located near bases.

Milton Bradley, the longtime friend of the troops, also stepped up to the plate.

The Great Depression was hard on Milton Bradley, and they were actually close to bankruptcy.

But the advent of World War II gave companies like Milton a chance to produce something useful. Despite having focused solely on games, Milton Bradley started making a piece of aircraft landing gear to bring in revenue. A

nd then they made a contract to produce games for the soldiers.

And for the families at home, Milton Bradley introduced two new games, Chutes and Ladders and Candyland, which could be then be found at USO centers.

Finally, there was one other company that made a huge agreement with the government and this time it was for inclusion in each soldier’s rations.

But for that the story goes back to 1936 and that Spanish Civil War that basically started World War II.

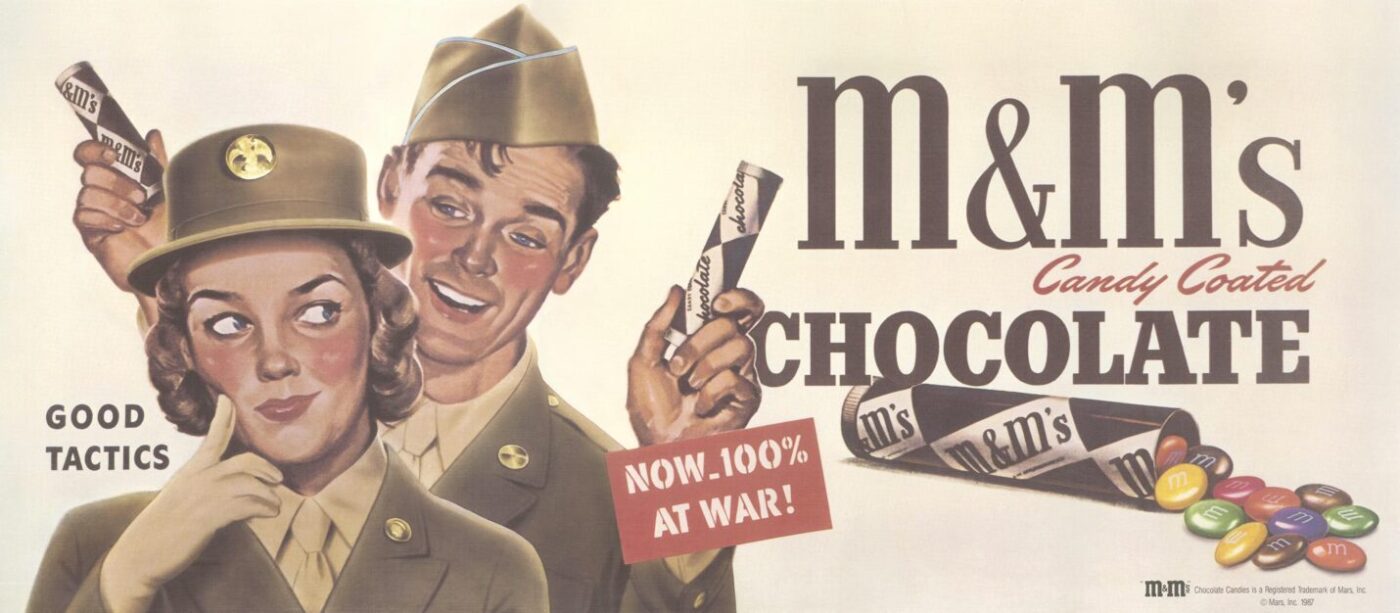

M&Ms for the Troops

The Mars Corporation was a huge maker of chocolate and chocolate candy. While Frank Mars ran the company, it was his son Forest who wanted to make a name for himself.

So in the 1930s, the Mars Company sent Forest to Europe to learn new chocolate making techniques. While there, he got curious about the Spanish Civil War, as did Ernest Hemingway, to which both made their way to the front lines.

While talking to some British soldiers who’d volunteered to be there, he noticed the soldiers were eating sugar coated chocolate candies in their rations. They were called Smarties, and they were made by Rowntree.

Forest had never seen them before. but loved the idea. The idea that the sugar coating preventing them from melting.

He didn’t think this candy process existed in the US and likely was not patented there. So, he came back with the intention of making it. But once he got back and started on the idea, the US had already been focused on World War II and had already enacted rationing, which included who could use sugar and who couldn’t.

Forest Mars could not.

But he did know Bruce Murray, the son of the president of Hershey, which was allowed to produce chocolate.

He and Bruce struck up a deal to make these sugar-coated chocolates. And Forest brought the idea to the warboard. Would the warboard buy these sugarcoated candies for the troops?

They loved the idea. They loved that the chocolate wouldn’t melt. And so Forest Mars and Bruce Murray started producing them.

But to make sure their chocolates would not get confused with any other candy. They wanted to print a design on each one. With the names Mars and Murray, they named the candy M and M’s and printed an M on each one.

But when you read about the USO and all that was done for the troops in World War II, neither M&M’s nor Coca-Cola nor Milton Bradley are ever mentioned in the first paragraph. That honor belongs to one man.

A man whose pure of heart contributions went unmatched. That man is Leslie Town Hope.

Bob Hope’s USO

Leslie was born in 1903 in England, the fifth of seven kids.

He had a great sense of humor and loved singing and dancing and performing on the streets for tips. He even won a Charlie Chaplin impersonation contest once.

In 1908, his family moved to the US to become US citizens and part of the fabric of the culture. Leslie’s life changed in 1921, however, when working as a lineman for the power company, a tree fell on his head, causing him to get facial reconstruction surgery.

And this new face would characterize the rest of his life.

By 1927, his singing and dancing would land him in the movie business. That is when he got into films starting with the Zigfreid Follies, working with Fanny Bryce. He also got to work with Ethel Merman and Jimmy Durante.

After a little bit of notoriety, however, it made him want to change his name.

Leslie Hope often got made fun of as “less hope”.

So, he chose the very American name of Bob and now he was Bob Hope.

Bob’s life would change again in 1938 when he starred in the movie The Big Broadcast with WC Fields. The song “Thanks for the Memory” became a hit, making Bob Hope a superstar in both movies and music.

It was just a couple of years later when a disc jockey friend, Albert L. Capstaff, asked if Bob would sing his song at March Air Force Base in California as part of a USO show he was promoting.

His brother was stationed at the base.

Bob loved the experience which came at the pinnacle of his career. In fact, he’d gotten so popular he was asked to host the Oscars, the year where the Wizard of Oz competed with the Gone with the Wind.

He would be asked to host the Oscars 18 more times in his career.

But performing for the troops stirred something in Bob. He wanted to do it again and again and again.

With recording music being banned, he had time. Over the next 18 months in 1941 and 1942, he traveled the length and breadth of the US, Europe, and the Pacific. And even after After World War II, he kept performing during the Berlin Airlift, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and even the First Gulf War.

Bob Hope made 57 tours for the USO and spent 48 Christmases with the troops overseas.

Bob is the only person in the 20th century to have been ranked number one in every category of entertainment: Vaudeville, Broadway, movies, radio, television, music, live concerts, and the USO.

Is that an accolade for Bob Hope, or is that the legacy of the USO?

I will leave you with this.

The words of 19-year-old Steven Lamar, who sent a note to Bob after his performance in Algiers in 1944.

“Dear Bob, I’ll never forget some of the thoughts that ran through my mind when you walked out on that thrown together stage on the dusty field near the airport in Algiers. I could see our living room at home and my mother sitting by the radio laughing at one of your gags. For a few seconds, I was back home and that did me more good than anyone will ever know.”

CUTTING ROOM FLOOR

To hear all the stories that hit the cutting room floor, you have to listen to the episode.

ABOUT THE SHOW

Let us tell you the story of the 20th Century, by tracing each event back to the original decisions that shaped it. You’ll quickly find out that everybody and everything is connected. If you thought you understood the 20th Century, you’re in for a treat.

Tracing the Path is inspired by storytellers like Paul Harvey, Charles Kuralt, and Andy Rooney.

INTERCONNECTED EPISODES

|

20th Century Trivia Window How did Trivial Pursuit and Jeopardy capture the popular imagination? |

|

The Official Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon It just so happens Tracing the Path is friends with the creator of the Six Degrees, and he’s only 1 degree away. |

|

Is Crayola Responsible for American Gothic? Grant Wood painted one of the most iconic images in the world, perhaps it was Crayola that gave him the confidence. |

|

The John Williams Legacy You Knew Nothing About John Williams of Star Wars? of Looney Tunes? of the Boston Pops? of Toto? |

|

Who Killed the American Dream The Day the Music Died is a lot more than a song. It’s the story of a nation in crisis. |

|

Was the Idea for m&ms Stolen or Inspired? Did you know in order for m&ms to become a candy, it would require 2 separate wars. |

SEE THE BIBLIOGRAPHY

SUBSCRIBE AND LISTEN (FOR FREE!)

RATINGS & REVIEWS

If you enjoy this podcast, please give it a rating and review.Positive ratings and reviews help bring Tracing The Path to the attention of other history lovers who may not be aware of our show.