TRACING THE PATH PODCAST

This episode of “Tracing the Path” challenges Plato’s assertion that truth can only be found in “the light,” arguing instead that darkness can illuminate new paths to knowledge and understanding.

The narrative weaves together several seemingly disparate stories, beginning with the legend of Saint Justice, whose martyred head continued to speak in defiance of his execution. This theme of overcoming darkness is then explored through the contributions of the Haüy brothers: René Just Haüy, considered the father of crystallography, whose discovery of piezoelectric crystals would later enable sonar, and Valentine Aüwy, who founded the first school for the blind, pioneering raised-letter reading.

These innovations paved the way for Louis Braille’s revolutionary six-dot system, which transformed literacy for the blind. The podcast further illustrates this theme through the invention of sonar, an “extra secret weapon” allowing navigation and detection in the ocean’s darkness, and the creation of the superhero Daredevil, whose blindness becomes a superpower thanks to sonar-like abilities.

Finally, the story concludes with the powerful friendship between Art Garfunkel and Sandy Greenberg, demonstrating how human connection and determination can help someone navigate a world without sight, ultimately proving that darkness doesn’t have to be a void, but can be a familiar friend.

Audio Hour:

If you run an activity group, classroom or “audio book club”, click here for more information on using Tracing The Path.

Throughout the episodes, every tune is somehow related to the topic. In the Twinkies episode, for instance, the discussion of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops Baseball team concludes with “Take Me Out To the Ballgame”.

How many do you recognize? And harder, how many can you name?

The ancient Greek philosopher Plato told a story about people who were stuck in the darkness of a cave and insisted that the only way these people could ever be part of reality, could ever be educated, could ever find the truth was if they left the darkness and stepped into the light. But Plato was wrong. His argument has been disproven four different ways. including the time Paul Simon wrote, “Hello, Darkness, My Old Friend.”

Our story begins in the year 278 when a young lad of nine went on a trip with his father and uncle and an attempt to rescue an imprisoned cousin. Imprisoned for his religious beliefs, Justus, the 9-year-old boy, was captured and confessed he too was a Christian.

But when pressed, he refused to condemn Christianity nor divulge the hiding place of his father and uncle. They needed to remain hidden in their dark spot to finish their rescue.

And for his confession of Christianity, Young Justus of Beauvais was beheaded. The legend still told today said this marty’d saint’s head continued to speak. This miraculous act happened in France between the towns of Beauvais and Senlis.

On that spot rose a town named after him, St. Just-en-Chasée. The town would be burnt down to the ground three times, including in 1636 when the Spaniards burnt down the church too. The church built in honor of Justus.

But every time it was destroyed out of the darkness, the town would rise again. It is from this town in the 1700s one family would prove Plato wrong, two different ways.

The Origin of Sonar

Just and Magdalene Candelo were full-time linen weavers in St. Just. They fell in love, got married, and started a family. In 1743 and 1745, they would bare two boys, Renée Just Haüy and Valentin Haüy. Two boys that would change the world.

Renée, named after the marty’d saint, was interested in music and church. He grew up to become a deacon and eventually a Roman Catholic priest. He attended the College of Navar for religious studies, but that is not the direction the universe had in mind.

His priesthood career took him to Cardinal Lamore College where he taught Latin. And it was this place he became friends with a man man who loved Botany. Because of that, Botany became a big interest of Renée, just as well. That is until he started looking at minerals and then minerals became his true love.

But it was an accident that shifted his life completely.

Having heard Renée had an interest in mineraology, he was asked to come look at some crystals a friend had collected. When he was holding a piece of calsite. He accidentally dropped it and it broke into pieces.

Picking it up and looking at it, he was mesmerized by the perfectly smooth plane the fracture had created. How could such a break create a glass-like surface? He wanted to know more.

Studying the fragments, he decided to make further experiments in crystal cutting, cutting them smaller and smaller until he found every crystal had a nucleus shape that couldn’t be broken down further.

His studies proved that crystals were made up of these nucleus shapes that were arranged in successive layers according to geometric laws of crystallization. Previously, crystals had been classified a different way.

But Renée Just’s discovery and publication changed everything.

Between 1784 and 1822, Renée Just published more than 100 reports detailing his crystal theories. Some of these would revolutionize the world as he was able to detail the pyroelectricity of crystals.

He had first detected it in an oxide of zinc where the electricity in crystals were strongest at the poles and almost imperceptible in the middle.

He became known as the father of modern crystallography which will be important later in our story. But that brings us back to his brother Valentine Haüy.

Because remember, this one family would debunk Plato two different ways.

Braille’s Humble Beginnings

Valentin’s journey followed closer to his father’s footsteps. Valentin was educated by the local abbey monks, the group that had given his father the weekly job of bell ringer.

It was through the monks that he learned to love languages. He studied Greek and Hebrew and eventually became the interpreter of King Louis 16th.

In 1771, while in Paris, he experienced a defining moment when he saw a group of blind kids being mocked at a religious street festival. It was that very moment, like a bolt of lightning, that made him want to start a school for the blind and give them a way to learn from the important books, to give them a chance to learn languages.

It wasn’t too long after that he came upon a very young blind beggar who would become his first student, Francois Lazar.

He could easily see that Francois’s darkness was not only because of blindness, but also because there was no way for him to learn. So, Valentin quickly developed a method of raising letters so they could be felt by the fingertips.

Similar to flipping a piece of paper over and tracing the letters you can see through the page, pressing hard enough, they would became raised on the other side. Valentin announced his success with this method in the journal of Paris in 1784 and then he opened his institute for the blind in 1785.

The same year his brother Renée was writing about pyroelectric crystals.

During the 1789 French Revolution, the Institute for the Blind had been taken over by the government and the group Renee just worked for, the Royal Academy of Sciences, was dissolved. But their role in the world was far from complete.

The Haüy family had just laid the foundation.

Which brings us to the next hero of our story.

One Barbier Step Closer to Braille

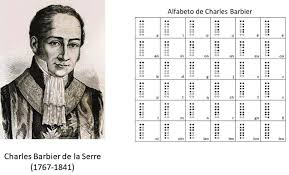

Not far from the town of St. Just-en-Chasée was the town of Valenciennes where Charles Barbier had been born in 1767.

Like most youth, Barbier joined the French artillery in 1784 and served during the French Revolution. In 1791, a law was passed by the French government giving the government the right to take the land of any noble that had immigrated.

Appalled at the idea, Barbier wrote a letter to President George Washington in the United States telling him how useful he would be if he was allowed to join the US military. But instead of waiting for the reply, Charles Barbier fled to America.

He returned to France a few years later when a friend of his from military training had risen to become leader of the French army. That friend was Mr. Napoleon Bonaparte.

But Barbier didn’t rejoin the military himself. Instead, he turned his eyes toward learning languages.

From his time, in his previous military career, the images of military life that still haunted him were the ones that happened at night, in the darkness when both sides of the conflict were afraid to come out. It was then that a soldier would light a match, to have some light to read the map, only to be killed by an enemy sniper. It made him so mad that maps and messages couldn’t be read in the dark.

On the flip side, he’d never liked traditional writing anyway. He thought it took too long to learn, leaving farmers without an education because they truly didn’t have time to master it.

So, Barbier set out to create an easier shorthand, or phonetic language, that didn’t take long to learn and could be read in any condition, including darkness. He also thought if he were successful, he’d provide this new tool for the blind, they too could escape the academic void of darkness.

He started with a 6×6 grid of dots that would represent the letters. Then he developed the tools necessary to create raised dots on paper that could be read by touching them with fingertips. (He was sure maps could also be made this way.)

In 1815, when the monarchy was restored post French Revolution, the school for the blind was removed from government control. Barbier saw a chance at getting his new shorthand language noticed. While Valentin Haüy was no longer there at the Institute for a Blind, the institution was still flourishing.

But having just retained control and there being a new headmaster, they weren’t ready to leave Valentin’s original curriculum and language of raised letters on paper.

In 1821, Barbie submitted again. This time, a new headmaster had taken over, and he was ready for change. He liked Barbier’s language and assigned it to some of the blind kids to learn and see what they thought.

The students loved it.

Valentin’s raised letter method was logical, but it made books huge, and because the letters had to be larger, the books were missing whole paragraphs, and they were heavy. Furthermore, Valentin’s plan was just for reading. There was no real way to create those raised letters to send notes of your own.

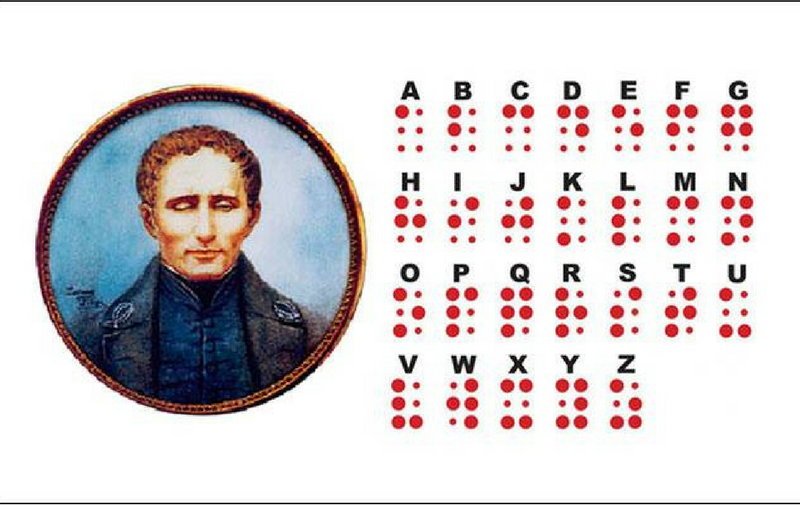

Barbier’s system had flaws as well, but it was much better than Valentin’s. In fact, one of the students took note of the flaws and started to think of an even better way. Little Louis liked Barbie’s shorthand, but knew it would need tweaking to become fully usable.

The Real Louis Braille

Louis was one of the few kids at the Blind Institute that was not born blind. He experienced an accident when he was three that fatally injured one eye, then progressed to the other. It is said that he was too young to know he was blind at the time, but instead often asked his parents why it was so dark.

He didn’t arrive at the blind institute until he was 10, but he arrived with zeal as well as the ability to play the cello. Music was the one thing he saw Barbier’s system lacked, as well as punctuation or capital letters.

Armed with what it lacked, along with the tools Barbier had invented, Louis created his own version and introduced it to the world in an essay in 1829 titled “Method of Writing Words by Dots for the Blind”.

The headmaster at the Blind Institute supported Louis’s improved version, but Louis still struggled getting the system out into the hands of the world, which was made even harder in 1840 when a new headstrong headmaster took over the Blind Institute and insisted on going back to Valentin’s, not using Barbier’s or Louis’s at all.

But that didn’t last long.

The students and teachers pushed for Louis’s raised dot design over Valentin’s. And so in 1844, it was brought back.

But Louis’s days were numbered. As a child, he’d contracted tuberculosis, and having never shed the sickness in full, he would have years of quiet, but it would always come back.

And at 40 years old, his body could no longer fight. Louis’s world would go dark one last time.

Sadly, he would never know that only two years later, the Blind Institute finally adopted his system, to which they named it after Louis himself, Louis Braille.

By 1882, almost the entire world was using the system he’d devised. Braille had become universal.

But it wouldn’t exist without the deeds of Valentin Haüy starting the Institute for the Blind.

From the outside, Braille is just a tool, just a language.

But for the blind community, Braille is the light in the darkness. In order to be educated, to find truth, and to contribute to society, the blind didn’t have to learn to see again. They merely had to reach out their hand to find the light in the dark.

Which brings us to the Next hero in our story, the Titanic.

It’s Dark Underwater, Too

In 1912, when the Titanic hit an iceberg, a wake-up call rang through the scientific community. There had to be a way to detect objects like icebergs before they got close to ships. And then just two years later, the German u-boat submarines lit a fire under every government.

There had to be a way for our naval submarine crews to see in the darkness underwater to find icebergs and other enemies.

For the US, the effort was being headed by the Naval Consulting Board which was led by Thomas Edison, and the non-governmental community had come together as well. The Naval Consulting Board, the NCB encouraged the civilian scientists to work together to find a solution.

General Electric, Western Electric, the Submarine Signal Corps and Sir Ernest Rutherford were all trying to work together to find a way to detect things in the darkness of the ocean.

Everyone involved had been briefed about the men who had discovered supersonics, Mr. Paul Langevin and Mr. Constantine Chilowski. Langevin had been a star pupil of Marie and Pierre Curie, and Chilowski was a Russian scientist in Switzerland, eager to work with his contemporaries in France.

Just after the Titanic event, Chilowski and Lanjivven were independently looking for an underwater detection system and both were using sound waves generated by the Pyroelectric crystals that Renée Haüy had identified.

With these pyrolectric crystals, they had developed a way to listen to sound in the ocean. The electric crystals would absorb the sounds that it heard, but they had a way to produce a sound that would bounce off objects and come back, telling the user how far away the objects would be.

This new technology would be called sonar. And yes, the brother of Valentine Haüy, who’ created the school for the blind that led to the invention of Braille was Renée Just, who determined the pyroelectric quality of crystals that would soon allow ships to see in the darkness of the ocean.

Sonar.

Sonar wouldn’t become the hero though until World War II.

That’s when the Navy began publicizing that sonar was the extra secret weapon that helped the Allies win. And because of that, magazines like Popular Science showcased how sonar worked and how the science of sound waves and pyroelectric crystals led to the successful hunting of icebergs and submarines.

Even pop culture rode the wave. In 1958, a book called “Listening in The Dark” took echolocation out of obscure zoology corners and into mainstream thought. Which brings us to the next hero in our story of combating the darkness.

Submariner Comic Book

Bill Everett was born in 1917 during World War I in Cambridge, Massachusetts to a longstanding American family. He had been related to a Harvard president, and a Massachusetts governor, a congressman, and also to the poet William Blake.

Billy was a voracious reader and artist who, like Louis Braille, had contracted tuberculosis as a child and spent a good deal of time in the American Southwest trying to recover.

At college age, he attended Vesper George School of Art before becoming a professional artist at a Boston Newspaper. His career moved him around a lot between comic books, pulp magazines, and other publications.

His first truly successful venture was a comic book character, an underwater superhero named Submariner, who like a submarine, had sonar that he used to communicate with fish.

That was 1939, before the Navy began bragging about their own secret weapon.

World War II would take Bill away from art for a few years before returning in 1946 and getting a job at Atlas Comics. He resumed his Submariner comic for a few years before Atlas unveiled the Fantastic Four in 1961, and changed their name to Marvel.

Riding high on the success of their new characters, Bill Everett and his manager Stan Lee decided to create a new hero. The Marvel blueprint of success, thus far, was taking someone relatable, like Peter Parker, and finding a weakness that would endear him to the fans.

For Peter, he had been bullied.

And on top of that, they added a moment of transformation where superpowers would show up, like the time Peter Parker was bitten by a spider.

So they decided to go with an ordinary man in New York City. But they wanted him to have already overcome impossible odds. So they made this man blind and a lawyer, meaning he had to have mastered Braille to succeed in college and pass the big lawyer bar exam.

And then his accident would be spilling radioactive goo on his eyes, thereby giving his eyes a super power sonar.

And while he fought for justice during the day as a lawyer, he’d fight for justice at night with his blindness, as a character named Daredevil.

Isn’t it amazing that this darkness, Plato explained, would rob you of education, was then turned on its head with Braille and sonar, and just a short while later would be considered a superhero’s super quality and skill?

Daredevil was released in 1964, the same year that the final hero of our story released the song that started this episode.

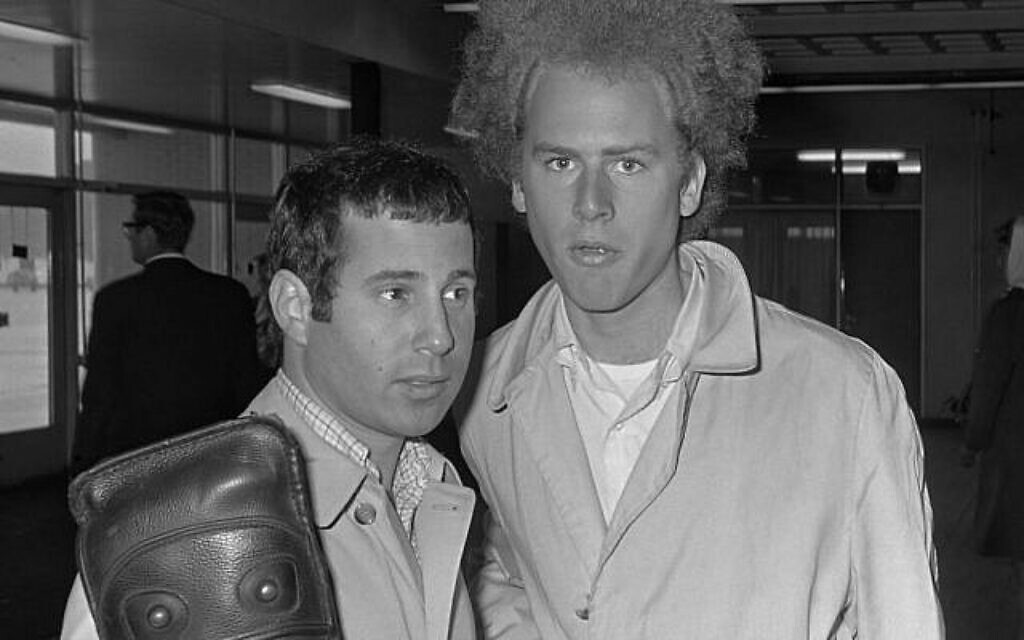

Simon & Garfunkel

You would know it because it begins, Hello Darkness, My Old Friend, and was written by Paul Simon and performed by Simon and Garfunkel. In a slight twist on our discussion of darkness, Paul Simon would often sit on the cool tile floor of his bathroom, turn out the lights, and use the darkness to create music.

On February 19th, 1964, he finished his latest song called “The Sound of Silence” that would take the world by storm and make Simon and Garfunkel famous. But Paul Simon isn’t the hero of this story.

That title belongs to his partner, Art Garfunkel. You see, Art and his friend Sandy Greenberg met and became friends the first week they attended school at Columbia University. They remained friends for all of college, but just before his junior year, Sandy got glaucoma and lost his eyesight.

Sandy immediately retreated to family in Buffalo, New York, unsure of what to do. It would be a new world living in darkness. But to his surprise, his roommate and friend Art Garfunkel showed up at his door in Buffalo and convinced him to come back to Colombia.

He promised he’d be his reader and would keep him up to date on his classes. After their first semester together, with Art and his two friends reading the textbooks, Sandy Greenberg had completed his courses with straight A’s.

He’d done that without braille, without sonar.

Sometimes all it takes is friends to overcome the darkness.

One afternoon, Art and Sandy found themselves at Grand Central Station in New York City with Art suddenly needing to leave for an appointment, leaving Sandy to get home on his own for the first time.

Terrified, Sandy stumbled around Grand Terminal and the rush hour crowd. He took a shuttle to Times Square, transferred to the one train, and got off at the 116th Broadway stop, where he bumped into someone at the gate at the end of their driveway.

It was Art.

Art Garfunkel had been there the whole time, silently watching from afar to make sure Sandy could do it. And while Sandy was very angry with Art, He was also elated with what he just accomplished.

It was not long before Sandy’s darkness was no longer the terrifying void, but indeed the old friend.

In 2020, Sandy Greenberg published his memoir titled “Hello Darkness, My Old Friend”. He said of Art, “He gave me the greatest gift of my whole life. After I made it home by myself, there were no limits.”

Plato’s idea that a man stuck in the darkness of a cave would never see reality, never be educated, didn’t know the Haüy brothers would one day open the door to a new definition of darkness.

Because Louis Braille would step up and turn a code of dots into an alphabet of imagination, and then his brother’s crystals would make sure even the ocean’s darkness was readable. While Art and Sandy proved the darkness doesn’t have to keep you stuck, it was truly the vision of Bill and Stan Lee who thought blindness would not be a big enough impediment to stifle a superhero.

Four moments, all asking the same question.

“When the lights go out, how do we find our way?”

CUTTING ROOM FLOOR

To hear all the stories that hit the cutting room floor, you have to listen to the episode.

ABOUT THE SHOW

Let us tell you the story of the 20th Century, by tracing each event back to the original decisions that shaped it. You’ll quickly find out that everybody and everything is connected. If you thought you understood the 20th Century, you’re in for a treat.

Tracing the Path is inspired by storytellers like Paul Harvey, Charles Kuralt, and Andy Rooney.

INTERCONNECTED EPISODES

|

How a Coffee Shop Changed the World Can you imagine drinking coffee with friends, talking about business, only to form a giant company that changed the world? It happened. Twice. |

|

Tarzan and Buck vs Bell From the he national culture came the “superhero” Tarzan and America’s worst piece of legislation. |

|

484 Year Documentary of Muscle Shoals It wasn’t just the music that made it famous? Can you hear Helen Keller? Or see Henry Ford? |

|

Who silenced Alfred Hitchcock? There can be two distinct meanings to the word Silenced. |

SEE THE BIBLIOGRAPHY

SUBSCRIBE AND LISTEN (FOR FREE!)

RATINGS & REVIEWS

If you enjoy this podcast, please give it a rating and review.Positive ratings and reviews help bring Tracing The Path to the attention of other history lovers who may not be aware of our show.