TRACING THE PATH PODCAST

This episode of “Tracing the Path” unveils the unexpected and far-reaching history of Lloyd’s of London, tracing its origins from a 17th-century coffee shop to a global insurance powerhouse. The story begins with Lorenzo de Tonti invention of the “tontine”, an early investment framework proposed to fund King Louis XIV, highlighting its core concept of increasing dividends for surviving investors.

After initial rejection in France, the story shifts to London’s maritime community gathering at Edward Lloyd’s coffee shop, where ship owners and “underwriters” developed the foundational practices of marine insurance.

The broadcast then connects Lloyd’s pivotal role in historical events, from delivering news to kings to insuring carpool vehicles during the Montgomery Bus Boycott, demonstrating its impact on the Civil Rights Movement. Finally, it showcases Lloyd’s unique and often quirky insurance policies, covering everything from celebrity body parts to the Loch Ness Monster, ultimately revealing its accidental debunking of the Bermuda Triangle myth.

Audio Hour:

If you run an activity group, classroom or “audio book club”, click here for more information on using Tracing The Path.

Throughout the episodes, every tune is somehow related to the topic. In the Twinkies episode, for instance, the discussion of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops Baseball team concludes with “Take Me Out To the Ballgame”.

How many do you recognize? And harder, how many can you name?

The Lottery-Like Tontine

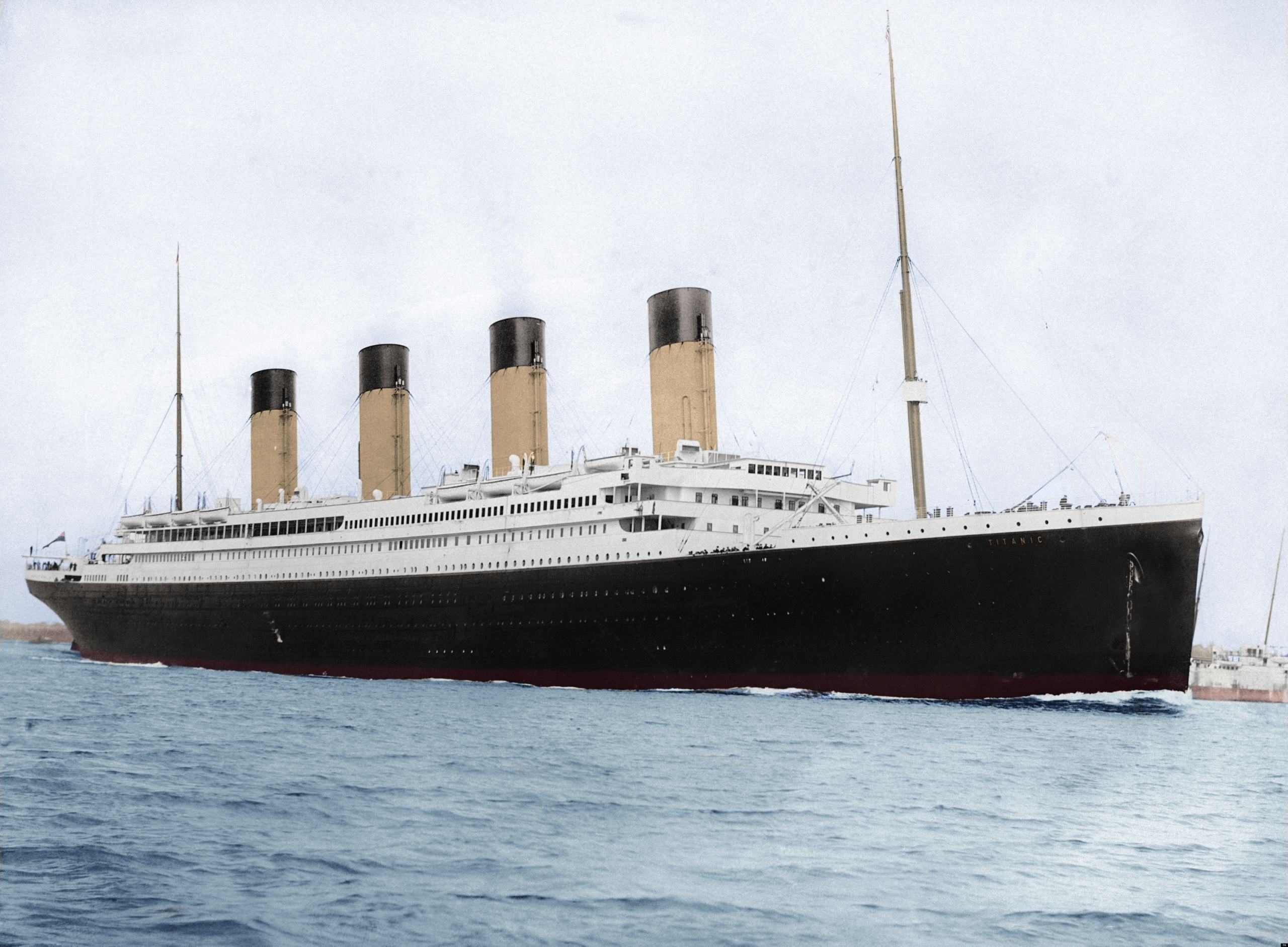

How could a story about financial instruments involve Robert Lewis Stevenson, Bruce Springsteen, Isaac Newton, Alexander Hamilton, the Titanic, Abbott and Castello, the Loch Ness Monster, and how, without it, the civil rights movement might have ended differently.

We begin our story in 1620 with the birth of Lorenzo de Tonti in Napoli, Italy.

Little is known of his childhood, but we do know that Lorenzo became the governor of Guyedi. Around 1640, there began political upheaval in Napoli with some suggesting that Lorenzo was a part of an attempted coup that failed.

No matter the reason for the upheaval, Lorenzo fled Italy for Paris, where he went to live with his friend and sponsor, Cardinal Mazarin.

The name Mazarin is probably new, but you are likely aware of the cardinal who preceded him, Cardinal Richelieu from Three Musketeers fame.

At the time Mazarin was in charge of the financial health of France working for King Louis XIV. The King had a voracious appetite for money since financing Europe’s largest military during so many wars was very expensive. He was always looking for funding ideas. That’s where Lorenzo de Tonti comes into play.

Lorenzo was aware of a funding concept he’d seen in Italy, but didn’t know all the details. So, he thought it through and filled in the gaps, eventually coming up with what he thought was a new funding concept. He named it after himself.

Instead of de Tonti, he named it the Tontine. He explained it to Cardinal Mazarin who was intrigued by the idea and thus presented it to King Louis XIV himself. Louis also liked it, but ultimately the French Parliament said no, and Lorenzo’s Tontine was dead in the water.

The Tontine he presented was a little bit like an annuity and a little bit like a lottery and perhaps it was part of the inspiration for today’s insurance instruments.

But at its heart, it was an investment framework. To King Louis XIV, they proposed it as a way to finance the military because it was low risk to France and ultimately low cost. The idea is simple.

The King would attempt to raise, for instance, $10 million by finding 10,000 people who would be willing to invest 1,000 each. In return, each would receive $20 in dividends each year. Exchanging $1,000 for $20 in dividends sounds small, but what makes a Tontine unique is that when one of the investor dies, his dividend gets added to everyone else’s who’s still alive.

So no matter what, every year until every investor is dead, France pays out $20,000 in dividends. That’s 1,000 people times $20 each per year.

When half the people have died, then everyone gets $40 a year. And finally, the person who lives the longest gets the $20,000 a year. And then when that person dies, France no longer pays anyone.

The original $10 million investment is theirs to keep.

For Parliament, forecasting when the last investor would pass away was impossible, so the cost was incalculable.

As a side note, Lorenzo did get some joy in the fact that his two sons, Enrico and Alonso, when they grew up, they ended up joining the military and became Navy explorers. In fact, both of them ended up making it to the New World.

Alonso is the one who founded and named the city of Detroit after the French Ville Detois. And Enrico also made a name for himself. While exploring the Great Lakes, he suffered an accident that blew off his hand and after that he traveled with an iron hand covered with glove. He became known as the man with the iron fist.

Having joined the military, Alonso and Enrico had it quite easy. For the average commercial shipper or boat owner, the rules of doing business got harder and harder. At one point, in fact, getting a sea loan that allowed shippers to get financing was even outlawed in France.

And so the commercial shipping community began to migrate away from the Mediterranean north to England where there still existed much freedom in shipping.

London’s Coffee House Culture

In the 1660s, London was the third largest city in Europe and they had the busiest seapport anchoring the world’s headquarters for commercial capital.

London was a highly congested city that had a bustling coffee house culture being that coffee, tea, and chocolate had just become part of society.

The Grecian coffee house was perhaps the most famous. It had become the destination and home of the scientific and philosophic community. You could find Isaac Newton, Edmund Haley, Martin Listister, and many other notables there.

In similar fashion, the Chapter Coffee House was where the book publishing world would meet.

Jonathan’s cafe was where investors and brokers met.

But that hustle and serenity were about to be disrupted. On October 9th, 1664, a large comet appeared in the night sky and remained visible for 80 days. While it was just a comet, it fueled anxiety in many and created the sense of impending doom that wasn’t there before.

It was almost like the Bermuda Triangle with everyone just waiting for the disaster to happen. But they didn’t have to wait long.

The next year 1665, the Bubonic plague hit London, killing 70,000 people. And then again the next year 1666, the Great Fire of London left another 70,000 people homeless. And London had no choice but to rebuild.

Incidentally, when this dark period hit London, some of the scientific community at the Grecian Cafe left town immediately. One of those was Isaac Newton. He went back to his family in Lincolnshshire. There he spent a couple of years away from the Grecian Coffee house.

That period historians have labeled his Years of Wonder because that is when he developed his new mathematical tool known as calculus and did his work on color spectrums and finally his discoveries around gravity.

So the dark, devastating years of London weren’t bad for everyone.

The need to congregate and be with others though was strong in London, which helped bring back the coffee shop culture quickly. Over 80 coffee shops opened in short order, including Lloyds on Tower Street, which brings us to the first heroes of our story.

The Community of Lloyds

Edward Lloyd’s coffee shop became the hub of activity for everyone in the shipping business. It became such an important location for communication, it got a write up in the London Gazette.

Ship owners would congregate for fun, betting on which ships would return, as well as sharing information on weather, pirates, insurrections, wars, and more.

Understanding risk was critical for those in the maritime community. A merchant with one ship was at much greater risk of business devastation than someone with a fleet of ships. So, everyone was looking for knowledge, tips, and actual insurance coverage for their travel.

While the community was made up of independent merchants, many saw Lloyds as a place to make additional money, ships that made it to their destination were easy money. So, Lloyds began renting out tables to entrepreneurs who were interested in selling insurance to ship owners.

Ship owners would list what they wanted insured. and the persons interested would write their names underneath the listing. They became known as underwriters.

A ship owner might indicate he wanted his load of tobacco insured to a port in Turkey. The underwriters would assess the risk and name the fee they needed to make. It was such a solid community that oftentimes speculators would band together to help cover the risks of others.

Perhaps the most controversial part of it all historically were the number of ships looking to get their slaves insured, which happened. Of course there’s no going back to rewrite that part of history.

But even though Lloyds was a loosely knit group of individuals what they were accomplishing from a communication and organization standpoint was hugely useful for the English government. Outside of the maritime community, no one had a communication network like Lloyds.

In fact, after Britain’s defeat of Spain in the battle of Portobello in Panama that opened the door to British trade in Central America, it was Richard Baker, the master of Lloyds, who delivered the news to King George at 10 Downing Street.

And in 1783, after evacuation day in New York City, it was Lloyds who informed the King that the British had left America. However, what Lloyds probably didn’t announce to King George was that George Washington, with his patriot army, triumphantly marched through the streets of New York, down Broadway, past Wall Street to Battery Park.

Which brings us to the next hero in our story.

The NYSE Coffee House

Like King Louis XIV, the US government was in desperate need for money after the Revolutionary War. It actually wasn’t sure it could survive economically.

Alexander Hamilton, whose office was on Wall Street, was the US Secretary of Treasury in charge of reviving the economy. Like Lorenzo de Tonti had done for King Louis XIV, Hamilton devised a plan for the US government to bring in money.

Not a Tontine, however, but bonds.

So the coffee shops around his Wall Street office became the stomping grounds for those who wanted to buy and sell the US bonds as well as the other stocks of big US companies.

Trading at the coffee shop wasn’t ideal, however, as it created many unfair situations with changing commissions and different prices. So 24 of the merchants who hung out at the coffee shop got together to hammer out an agreement that would bring stability to the trading of securities.

The agreement would lay out the commission structure, the rules of conduct, and more. They called it the Buttonwood Agreement, for it was signed below a Buttonwood tree.

These financial guys also wanted to build their own facility on Wall Street and agreed to get investors to fund it. But instead of using bonds like Hamilton had done for the government, they decided to create a Tontine. And decided to call their facility the Tontine Coffee House.

When it was finished, coffee was served on the first floor while trading took place on the second floor. That is until 1817.

That is when these financial gurus decided to formalize the group with a written Constitution, detailed rules, and the layout of fines for misconduct.

The this new group that also started in the Tontine Coffee House would be called the New York Stock and Exchange Board.

They would be the start of the New York Stock Exchange, which takes us back to Lloyd’s coffee shop in London.

Lloyds had become masters of shipping information, so much so that they had begun publishing the information in a paper called “Lloyd’s List” that merchants now paid to subscribe to.

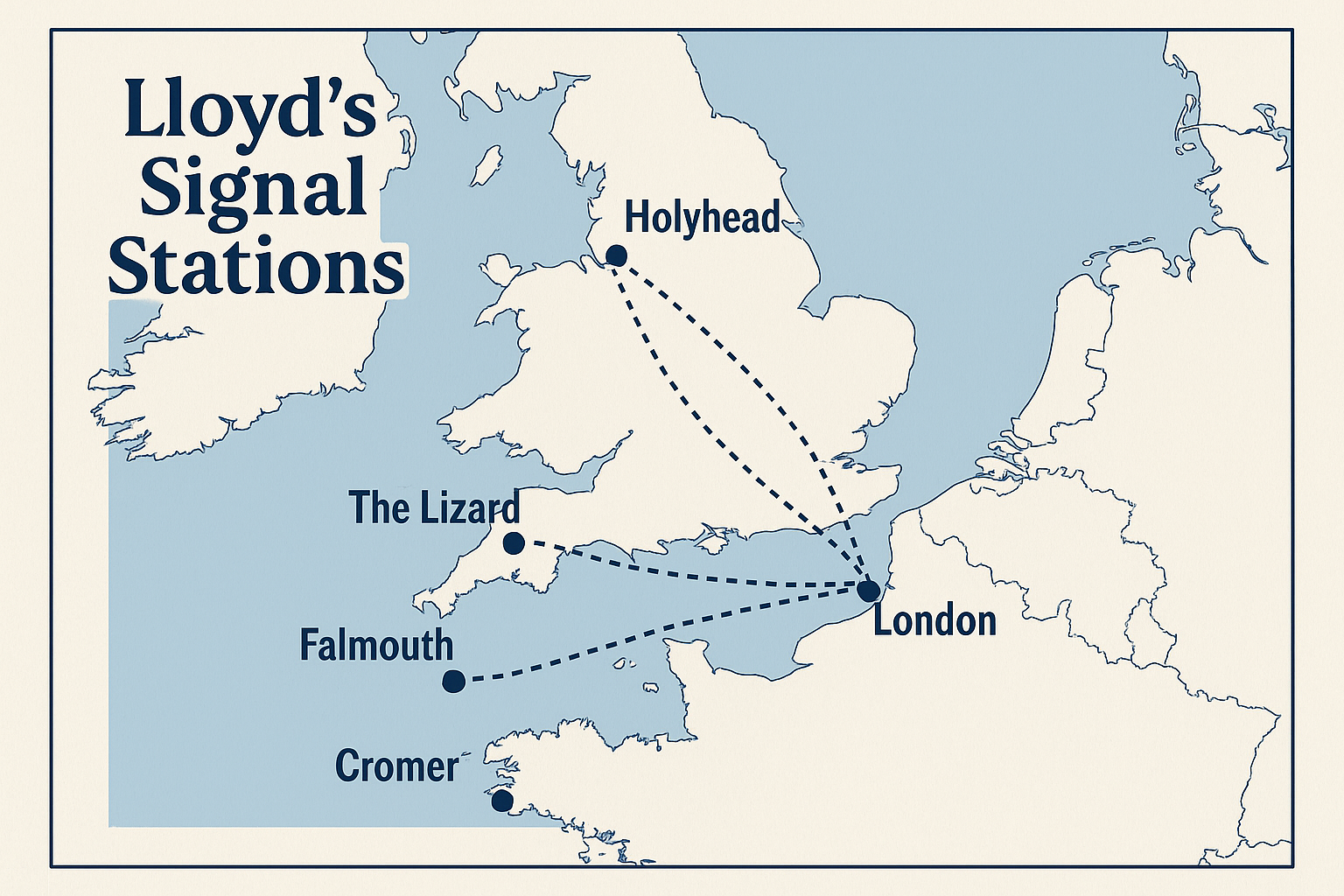

Around 1810, they started building a network of signal stations from the hilltop locations along the coasts. The stations used flags, semaphore, and telescopes to gather information and relay it back to Lloyd’s agents.

In many cases, they worked hand-in-hand with the Stevensons in Scotland who were the pre-eminent lighthouse builders. The Stevenson’s were a family outfit headed by Robert and his two boys.

Robert had been known for inventing flashing and intermittent lights.

They helped Lloyds spot the perfect locations for their communication stations. Lloyds also arranged with the railways for its agents to telegraph reports to London when they had shipping information.

And in 1847, they worked out an agreement with the electric telegraph company to use their lines.

Agents as far as India and Australia discovered ways to transmit reports and in 1866 the first undersea cable was laid between Ireland and Newfoundland in Canada.

But despite the commitment to infrastructure, Lloyds was still an informal marketplace of independent merchants.

By 1870, they found themselves with more and more of their members working full-time as underwriters instead of as just part-time merchants as always had been. So to gain more legal rights and formality, Lloyds petitioned English Parliament to pass an act making them a legal entity.

On May 25th, 1871, Parliament passed an act making Lloyds of London an official insurance marketplace, meaning Lloyds of London and the New York Extract Exchange had both started as coffee houses.

The Parliament Act stated Lloyds existed for three reasons.

- One, for the conduct of marine insurance.

- Two, for the protection of the interests of the members.

- And three, for the publication and distribution of shipping information.

The only thing it didn’t foresee was how Lloyds would one day change the world.

The Lloyd’s network had grown to 1,000 agents offering insurance solutions to every business connected to shipping. As technology changed shipping, Lloyds added aviation and auto insurance.

And in 1898, they worked with Guglielmo Marconi in building a wireless communication network.

As for the New York Stock Exchange, the last member of its original Tontine they put together, died in 1871, leaving all future profit back in the hands of the New York Stock Exchange.

And the Tontine itself, that would become an almost extinct financial model, except for one small thing.

The Lighthouse Boy Learns to Write

Remember the Stevenson Lighthouse Engineering Firm in Scotland? They were the ones that helped Lloyds find communication stations. It was run by Robert and his sons David, Allan, and Thomas.

In 1850, Thomas had a son of his own, and as Thomas had followed his father in the lighthouse building business, he hoped his son would follow him.

But that didn’t happen.

Thomas’s son grew up to become an author.

And after learning about the concept of a Tontine, he thought it would make a great story. Because in a Tontine, it is ultimately the last person alive who makes all the money. Thus, he thought it plausible that someone in a Tontine might actually murder the other members to be the last man standing. A

nd so, in 1889 in Scotland, the Tontine murder mystery was published by the grandson of the lighthouse engineers.

The book was called The Wrong Box and the author was Robert Lewis Stevenson.

Which brings us full circle to the 20th century.

The one in which Lloyds changes the world.

Lloyds Passes the Tests

Lloyd’s role in the world would be foreshadowed by one man, an underwriter named Cuthbert Heath.

Cuthbert would set the tone for the entire 20th century. He started by pushing Lloyds to new places by offering a series of non-marine insurance policies like burglary, fire, and earthquake insurance. He also aggressively went after international business, garnering many accounts in the US.

And then in 1906, Lloyds would find a way to shine.

On April 9th, 1906, a major earthquake struck San Francisco. The earthquake destroyed huge sections of the city, but it was actually the ensuing fires that caused the most damage. Most of the citizens didn’t have earthquake insurance, but they did have fire.

However, since the earthquake caused the fires, many insurance companies declined the claims.

But not Cuthbert Heath of Lloyds.

He sent a cable from London to his San Francisco agent that said one thing.

“Pay all policy holders in full, irrespective of the terms of their post.”

Doing as much, Lloyds paid out $50 million in premiums. That is more than 1 billion in 2025 dollars. Because of that level of service, the United States became Lloyd’s largest market. Lloyd’s arrival in the US came via disaster, as did Lloyds itself after the Great Fire of London.

Six years later, Lloyds would get another high-profile test.

On January 9th, 1912, broker Willis Faber and Company came to Lloyds to ensure two ships for their client, White Star Line, the Olympic and the Titanic. For Lloyds, it was a monumental case that would involve many members partaking.

The whole of the Titanic alone was worth 1 million British pounds. Then, 3 months later, almost to the day, the Titanic hit an iceberg and sank.

But did you know the only people who knew it was sinking was Lloyd’s communication station in Nova Scotia? The one that they had installed with Marconi’s wireless equipment. It was the Nova Scotia station that would alert the world.

Despite the high level of claims, Lloyds paid out all its members within 30 days.

The entire business model of Lloyds was to be there when people were at their lowest and needed the most help.

But there was one case where Lloyds was able to be there for the entire world.

It was 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama, where local laws kept the public buses segregated with black riders sitting in the back and white riders in the front. On December 1st, 1955, Rosa Parks got on the bus and sat down in the middle section.

When the white seats were full, the driver asked Rosa Parks to move to the back, but she refused.

For the activists behind the civil rights movement, they had been waiting for a case to test the legality of segregation. While others had been arrested for sitting in white person’s seats, none of them were the right people for the test.

But when the quietly strong-willed Rosa Parks with an impeccable reputation was arrested, it was time to act.

Activists quickly found an attorney to represent Rosa in court. Volunteers got together to organize a one-day boycott of the buses. That one-day boycott would happen on Rosa Park’s court date.

Two students at Alabama State College secretly printed 35,000 leaflets about the boycott to hand out to the community.

Local pastor Martin Luther King Jr. was asked get involved, to which he helped distribute the pamphlets and helped organize a citywide car pool for those who needed transportation during the boycott.

Rosa Parks’ court hearing lasted 30 minutes where she was found guilty of violating state law and fined $14.

That night, 15,000 people showed up at the Holt Street Baptist Church to hear all about the case and what was next. And when Martin Luther King asked the crowd if they wanted to continue the boycott. They overwhelmingly said yes.

That meant volunteers had to go into overtime, creating a full transportation plan.

Northern sympathizers sent station wagons and other cars to help create a transportation network of vehicles for the community to use during the boycott.

But after the boycott lasted several weeks and the city was losing precious bus fair revenue, city officials pressured local insurance company companies to drop the insurance of the carpool vehicles.

It was illegal to drive without insurance.

But the activists were smart and prepared. They contacted an insurance agent in Atlanta, Mr. TM Alexander, to help solve the problem. He in turn reached out to Lloyds of London to get all the carpool vehicles covered for an indefinite amount of time because they weren’t going to rest until the problem was resolved.

And Lloyds of London agreed.

They insured each car for $11,000, which allowed the Montgomery bus boycott to continue for $381 days until the Supreme Court ruled segregated buses were not legal.

All because a guy named Edward Lloyd opened a coffee shop in London for the people in the shipping business. 🙂

CUTTING ROOM FLOOR

To hear all the stories that hit the cutting room floor, you have to listen to the episode.

ABOUT THE SHOW

Let us tell you the story of the 20th Century, by tracing each event back to the original decisions that shaped it. You’ll quickly find out that everybody and everything is connected. If you thought you understood the 20th Century, you’re in for a treat.

Tracing the Path is inspired by storytellers like Paul Harvey, Charles Kuralt, and Andy Rooney.

INTERCONNECTED EPISODES

|

The Comet That Saw it All The actual significance of Halley’s Comet |

|

187 Years Behind Martin Luther Kind’s Dream We all learn about the “I Have a Dream” speech, but few know where it comes from. |

|

Criminals, Oak Trees and the Resolute Desk How did the Resolute Desk End up in the White House? |

|

The Hands that Changed the World Have you ever heard the origin story behind Rolex |

SEE THE BIBLIOGRAPHY

SUBSCRIBE AND LISTEN (FOR FREE!)

RATINGS & REVIEWS

If you enjoy this podcast, please give it a rating and review.Positive ratings and reviews help bring Tracing The Path to the attention of other history lovers who may not be aware of our show.