TRACING THE PATH PODCAST

This source traces the surprising evolution of information organization, beginning with Sir Francis Bacon’s 16th-century emphasis on empirical evidence and a scientific method to acquire knowledge, which challenged traditional wisdom.

The story then shifts to Carl Linnaeus, who, overwhelmed by the sheer volume of natural specimens, developed the index card in the 18th century as a revolutionary tool for systematic classification. This innovation laid the groundwork for library cataloging, most notably with Thomas Jefferson’s use of Bacon’s system for the Library of Congress and later, Melville Dewey’s creation of the Dewey Decimal System.

Ultimately, the development of these organized information systems, including the vertical filing cabinet, culminated in J. Edgar Hoover’s visionary application of index cards to track individuals, leading to the formation and effectiveness of the FBI in managing criminal intelligence.

Audio Hour:

If you run an activity group, classroom or “audio book club”, click here for more information on using Tracing The Path.

Throughout the episodes, every tune is somehow related to the topic. In the Twinkies episode, for instance, the discussion of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops Baseball team concludes with “Take Me Out To the Ballgame”.

How many do you recognize? And harder, how many can you name?

It’s such a simple idea and yet for it to become fully complete, it took 400 years. Darwin might be the originator of the origin of species but today, we’re exploring the evolution of a concept, one that resulted in the capture of John Dillinger, the Unabomber and Bonnie and Clyde.

Have you ever heard the phrase knowledge is power?

Well, it was coined back in the 1500s by a statesman and philosopher named Sir Francis Bacon.

He was a lawyer, an attorney general, a member of the British Parliament, and an author on many topics. The one thing he is most famous for is his thoughts on knowledge, empirical evidence, and the need for an objective scientific method in solving problems.

He was one of the first to argue that knowledge of the natural world is best acquired through direct observation, experiments, and the testing of hypothesis. Bacon believed that much of the factual information and science that was being taught were in fact not facts at all, and that the following of tradition, authority, and abstract reasoning were the basis of these untruths.

He went further and proclaimed humans largely have four weaknesses that must be overcome to reach truth. The first he labeled the cave, suggesting that we tend to see the world through the lens of our own experiences and personal viewpoint, as if we all live in our own cave.

The second he called the tribe, which is where we tend to see patterns in order where there isn’t any.

The third is language and our inability to communicate effectively with others leading to misinterpreted conversations, instructions, and conclusions.

And the fourth is our learned prejudices based on the knowledge of how things have always been.

Because of our natural biases, he thought it was best practice to have concrete systems in place that would prohibit human tendency.

In his book, Advancement of Learning, for instance, he proposed a detailed systemization of the entire range of human knowledge and boiled it down to three parts: reason, memory, and imagination.

It’s hard to imagine dividing the world into three categories, but no one balks when we say person, place, or thing. But he did and he included his logic for the three.

- Reason is the understanding of general principles which he links to philosophy and the pursuit of knowledge.

- Memory is history but also it is all the knowledge of singular individual matters of fact.

- And imagination was the faculty of knowledge that explored new ideas and concepts including poetry and the creative arts.

And he felt everything would fall into one of those three categories.

Sir Francis Bacon was part of the period of time known as the scientific revolution where knowledge was expanding daily.

New technologies like the telescope were expanding the heavens with people like Copernicus.

It is Sir Francis Bacon during the scientific revolution that gives us the first piece of the puzzle that leads to the FBI.

The Evolution of Index Cards

I am compelled to remind you, however, that the FBI that you see on television and movies where they drive around in SUVs participating in gunfights and unused warehouses is not really the FBI. The most important word in the FBI’s title is investigation.

Exactly what Francis Bacon was doing with knowledge. The second big player in the formation of the FBI was Carl Linnaeus. Carl was a product of the scientific revolution which lasted from the year 1500 to 1700 as he lived from 1707 to 1778 in Sweden.

He was a biologist and physician who formalized the system of naming organisms and is also considered the father of modern ecology. In 1735 he published a book called Systema Naturae which set out the name of all of nature’s living organisms.

It was the document that first gave the name Canis Lupus, or canine, to dogs, for example. Prior to Carl there was no universal system.

This type of naming is called binomial nomenclature. Two names. His classification system indexed each organism by its species, genus, family, order, class, family, and kingdom, which was an incredible amount of information to manage.

By the time Systema Naturae reached its 10th volume in 1758, it included 4,400 species of animals and 7,700 species of plants. People all over the world were sending their specimens to Linnaeus to be included in the upcoming update.

With the enormity of information, He needed a new way to organize to manage the indexing of the natural world. It is no surprise he needed a different method.

In fact, the whole process started with him collecting plants in the woods of his native southern Sweden. There was no grand plan to begin with, just him taking notes and notebooks. And Carl wasn’t typically seen as an organized individual. Some said he looked like a markedly unshaven man with dusty shoes.

But now as botanists were crawling every last hectare of earth, he was overwhelmed. His notebooks were great, but finding small details inside them was a heroic task on its own. His Eureka moment came when he was cataloging the butterflies of Queen Lovisa Ulrika’s collection.

Being away from home without his normal notebooks, he decided to grab a deck of playing cards that all had white backs and used one for each butterfly, writing the information he needed on the back of each card.

Properly organized, he could then easily retrieve any card in the stack, review it, add information, and put it back in the stack. He could even add more cards. He found he had much better control with these indexed cards.

When he got home, instead of playing cards, he made similarsized cards out of a stiff white paper and called them index cards.

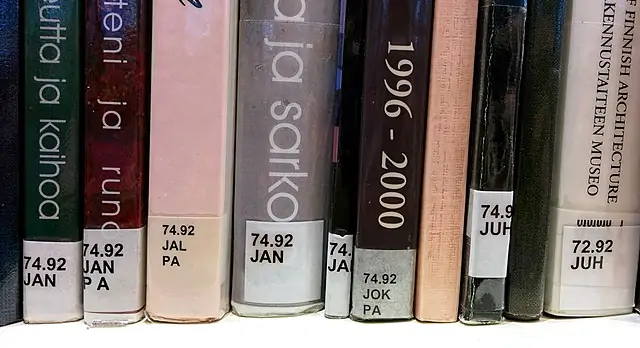

You can actually see some of Lanaeus’s original index cards at the Linnean Society of London in Sweden, to which everyone is amazed how remarkably similar they are to what we still use today.

Just as index cards brought organization to the living organisms of the world, they would soon do the same for the chaos of the world. And believe it or not, but the invention of the index card was a turning point in the historic ical relationship between knowledge and power. As you will see, it wouldn’t be long before the libraries of the world would catch on to the idea of using cards as an organizing tool.

The Library of Congress

Libraries had been recording all the books they had in tablets, a sort of notebook. But eventually, every tablet would run out of space for new entries. Either the tablet would have to be rewritten or a new one started.

Both were laborious.

In 1791, during the French Revolution, libraries were having a revolution of their own, resorting to using cards, and they actually started with playing cards, which were readily available everywhere.

While switching from notebooks to cards made it easier to manage where the books were, it was still only half of the revolution libraries needed.

For the books themselves were still very much fixed objects in the library. The card would merely tell which shelf the book was on and that was often determined by when the library acquired the book and also by the size of the book.

For example, a coffee table- sized book could not go on the shelf that was only 7 in tall.

Which brings us to the year 1800 when the American Legislature voted to establish the Library of Congress. At the time, the US capital was located in Philadelphia, but was moving to Washington, DC.

Most of the founders of the US had received rigorous classical educations and were avid readers. The congressmen, who’d had access to sizable libraries in New York and Philly, decided a space needed to be created and maintained in Washington to aid Congress in their research and legislative duties. So, $5,000 was allocated and 3,000 books were moved to a small room in the capital building in DC.

The space was small and the books few, so there wasn’t much of an organizational structure. The War of 1812 had some brutal outcomes for this new America. In 1814, British soldiers entered Washington DC and burnt down the US capital, including the small office that housed the Library of Congress.

All of the books were destroyed.

It was actually Thomas Jefferson who stepped up to the plate to help solve this new problem. He had been collecting books for 50 years and had a personal collection of 6,487 books which he offered to sell to the US government to replace the lost books of the Library of Congress.

They agreed and paid him $23,950 on March 13th, 1815, which would be about $490,827 today or $75 a book, which is perhaps reasonable if they otherwise would have had to ship books from the United Kingdom back to the United States.

But without a repaired capital building, a place had to be found. Therefore, and can you believe that from 1815 until the capital was restored in 1818, The official Library of Congress of the United States of America was located at the corner of Seventh and East Streets in a room in Blodgett’s Hotel, where incidentally the US patent office already was.

To make it even more convenient for the US government, the books arrived already categorized.

Thomas Jefferson had collected the books for 50 years and was familiar with Sir Francis Bacon’s classification system based on reason, memory, and imagination, which he had used to index his own collection.

So, since the books were in somewhat of a temporary location and would one day need to be hauled off again, they weren’t reorganized a different way. In fact, in 1818, when they went back to the capital, they still weren’t reorganized.

The Library of Congress remained organized by Francis Bacon’s method until 1897. Can you imagine that?

That reorganization is where the story goes next. But the library is not the only thing. That does take us back a few years to the Civil War era and involves three new heroes. Ainsworth Rand Spofford, Elihu Root, and Melville Dewey.

The Dewey Decimal System

Melville Dewey was born in 1851 in Adam Center, New York, an area of upstate New York that attracted every great cause that created great debate. Suffragists, Baptists, Mormons, Abolitionists, Chautauquans, and the temperance community all made upstate New York a home base.

It seemed everyone there needed to be passionate and dedicated to something. For Dewey, it was giving the right of free school and free libraries to everyone.

That was his passion.

Dewey attended Amherst College where he graduated and was a immediately hired to manage their library and create a new classification for it. He was fascinated with the concept of reorganizing the library all through college.

So they knew he had the passion to improve it.

Unlike most libraries, however, Amherst was already a bit progressive in their library classification system. They weren’t categorized by what shelf the book was on, but rather by what the author’s last name was.

It was alphabetical.

And while it made finding books relatively easy, a novel might end up next to a geometry textbook, making it a less useful place for finding related topics.

Dewey was already familiar with some of the classification ideas already being tried, but he felt they all had a flaw, and Bacon’s of course wasn’t robust enough. Then one day, while in church listening to the sermon, an epiphany hit him.

Dewey thought each book could have a base number followed by a decimal followed by more numbers to further classify it down.

The Dewey decimal system.

So in 1873 he began to implement this library classification system using the cards Carl Linnaeus had invented. What the Dewey system did was change the relative position of the book on the floor for guests.

It was no longer tied to a shelf and no longer tied to the author’s last name.

Now you could find your book on the shelf and several similar near it. And it didn’t matter how many books were added. Each book had a number added to its spine and then a card was created for the title of the book, and a card was created for the author and one for the subject.

When other librarians inquired, Dewey would teach them everything, including the style of print they needed to use when they were filling out the cards.

In 1876, however, the 100-year anniversary of America, Dewey left Amherst to live in Boston to pursue another idea.

There, at the age of 25, he opened the Library Bureau, a store, a supply store for the nation’s libraries. He sold cards, card cataloges, library furniture, and supplies, and used his library contacts to get the word out.

By 1900, most librarians were buying from the library bureau. And with the store being the only real place to get library supplies like cards and card cataloges, the Dewey decimal system had built-in success.

The Library of Congress, however, had different plans in its early life.

The 1814 burning by the British wasn’t the only obstacle The Library of Congress had to overcome.

In 1924, a rogue candle left burning destroyed much of the library again. And in 1851, a faulty chimney flu caused 35,000 of the 50,000 books to go up in flames.

In 1853, Congress appointed an architect to build a fireproof room for the books, which President Franklin Pierce pronounced to be the most beautiful room in the world.

Through its natural growth, head librarian Ainsworth Rand Spofford got permission to add two new fireproof wings and to open it to American citizens, not just Congress.

Spofford had actually been appointed to the position of Librarian of Congress by President Lincoln. He’d gotten Lincoln’s attention years earlier when he’d published an anti-slavery pamphlet. And he also had some influential friends as he had founded the Cincinnati Literati Club which Rutherford B. Hayes, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Booker T. Washington, Robert Frost, and Mark Twain had become members.

Spofford largely held the view Jefferson did for the Library of Congress. He wanted it to one day be open to people and not just Congress. He also felt that a democratic form of government depended on a comprehensive base of knowledge, information.

He helped grow the library to include international documents, two copies of every copyrighted registration, and he had included a copy of every book, pamphlet, map, print, photograph, and piece of music.

In 1872, he convinced Congress the library needed its own building.

As the library grew immensely, it was clear Francis Bacon’s classification system wasn’t going to be enough. Francis had based his own system on what books and knowledge were available to him then, which reminds me of his cave theory that he espoused.

And Dewey’s decimal system wasn’t going to be enough because it was based on what a library would typically house.

The Library of Congress needed a system that could organize everything. So in 1897, the head catalogers, James Hansen and Charles Martell were tasked with developing a new scheme, the first outline of which was developed in 1904.

And while the index and management of books and information worked inside the library, there was still a piece missing that would revolutionize the rest of the world.

The Rise of the Vertical Filing Cabinet

The historical record isn’t clear here. All we truly know is that two different groups came up with the same idea at about the same time. Outside of cards, information was largely managed in ledgers, books, and reports.

Storing information in an office meant recording it in tightly bound ledgers that were stacked or stuffed into wall cubbies. The advancement libraries made with cards basically didn’t affect the business world at all.

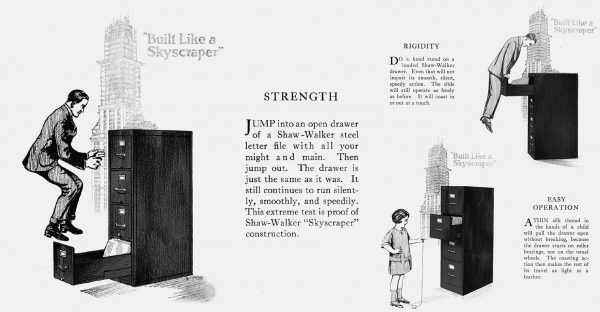

That’s when Melville Dewey’s Library Bureau store, and separately a man named Edwin Seibles of South Carolina, came up with the idea of vertical storage filing cabinets.

At first, the filing cabinet made little headway as a commercial product, but then the cabinet got a boost. A small magazine called “System” was started to give companies smart business advice and that actually dedicated one of their issues to vertical filing.

They introduced the idea for the first time in history that information could be at your fingertips.

They proposed the idea of taking pages out of bound ledgers and putting them in folders with related information. Those folders would then go inside the vertical filing cabinet which would be easy to retrieve when needed.

They included a graphic that compared vertical files to skyscrapers and how little space they took up on the floor.

And that article reached the desk of Elihu Root, the new Secretary of War under President McKinley. And for Elihu, it was life-changing.

Getting the information he needed to make decisions frustrated him immensely. The clerks had to sift through press books. And copy books were filled with incoming and outgoing correspondents in chronological order.

There was no cross-linking, no way to make bigger decisions based on any real data.

It was then in 1905 that he single-handedly ordered a numerical vertical filing system be immediately adopted in his government offices, which became a milestone in the history of storing and organizing data.

Now he could have easily accessible folders on all major topics available at his fingertips.

Now, with cards, card cataloges, numerically ordered filing cabinets, that brings us to the crux of our story, the FBI.

The Creation of the FBI

By 1900, US cities had grown tremendously. There were now more than 100 cities with populations over 50,000, and crime had grown along with them.

Clashes between striking factory workers and owners were becoming violent. Corruption like Tammany Hall was present.

Blacks were seeing no benefits of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Gangsters like Al Capone and Babyface Nelson were emerging, Upton Sinclair had pointed out poor labor conditions and the anarchists were making the country uneasy.

The anarchists were the first modern-day terrorists hellbent on taking down the government. But the panic didn’t actually begin until September 6th, 1901.

A 28-year-old named Leon Czolgosz lost his factory job and found solace in the messages of the anarchists. So he took a train to Buffalo, New York, bought a gun, and assassinated the visiting President McKinley.

And then Teddy Roosevelt, with a strong hand, took on the role of president.

Roosevelt had a no nonsense approach to corruption, which he’d proven during his six years as civil service commissioner and two years as head of the New York Police Department.

Teddy Roosevelt set the story in motion in 1906 when he appointed Charles Bonaparte as his attorney general, and yes he was the grand nephew of the famous French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte.

Charles had met Roosevelt years earlier at a reform event where they hit it off immediately laughing at their common convictions.

In one such conversation with the Border Patrol, Roosevelt suggested that they only hire candidates who passed the marksman exam, to which Charles Bonaparte replied in jest, “How about you let the candidates shoot each other and then just hire the survivors?”

So they had indeed built a rapport.

But soon after his appointment, Charles Bonaparte realized he had no means by which to tackle the rising tide of crime. The Attorney General’s office had no staff and no investigators.

So he had to borrow agents from the Secret Service to get his job done.

But when Congress found out, a little politics got in the way and they decided to block his ability to borrow Secret Service agents. So Bonaparte had no choice but to create his own staff of agents.

He got 34 agents together and they became the Bureau of Investigation, BOI.

And since Congress had entrusted the Department of Justice with handling everything related to interstate commerce, Bonaparte had the Department of Justice use his Bureau of Investigation for any investigative tasks.

By 1914, this bureau had investigated politicians and traffickers.

And now that World War I was a threat, they were tracking German saboteurs and other anti-American activists.

By 1915, the bureau had 350 agents. Two years later, Congress passed the Espionage Act and the Sabotage Act facing World War I threats, giving both responsibilities to this Bureau of Investigation.

While it is not often discussed, there was a general worry infecting the population, after World War I, that the Russian Bolsheviks were present in the US. There were socialist revolutions all over the world and the anarchists once again started wreaking havoc in America.

It all came to a head in 1919 on June 2nd, 1919, a series of bombs exploded all over the US, all around 11 p.m., targeting government officials, judges, and other prominent figures, including the pacifist attorney general at the time, Mitchell A. Palmer.

That’s when the new director of the Bureau of Investigation, created a general intelligence division and brought in a bright-eyed 24-year-old to run it.

But what exactly would a 24 year old bring to the table? And would he know anything about tracking down radicals?

John E. Hoover was born on New Year’s Day 1895 in Washington DC.

He was the ultimate student in choir, the debate team, ROTC, the track team, and he was even elected Validictorian, though he didn’t have the top grades.

At that time, you could go straight from high school to law school, which is what John did. He stayed near home and attended George Washington University.

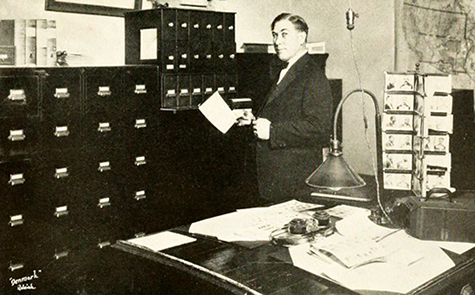

To make money, he got a job in the cataloging department at the Library of Congress and attended law school at night.

John was a superstar at the Library of Congress and got to work with Hansen and Martell who had created this new Library of Congress indexing system. John’s job in cataloging was to create cards for everything that came in and then put notations on the cards indicating cross reference points and information.

He could see immediately how this system could be used everywhere.

During his law school, World War I had heated up and the call for young Americans to get ready to fight had begun. Unfortunately for John, however, who wanted to enlist, his father had lost his job, which made John the bread winner of the family and ineligible to go fight.

Wanting to be a part, however, his uncle arranged for him to be working in the new war emergency division at the Justice Department, which he started the exact day after he graduated from law school.

He got promoted at the Justice Department pretty quickly to head of the Division of Alien Enemies where he started a card catalog to track people they suspected to be threats, mainly Germans in the United States.

That’s when the anarchist bombings took place, and the Bureau of Investigation realized they needed someone who knew how to organize all the information to make the bureau a useful agency.

So, John E. Hoover was put in charge of this radical division, choosing, however, to go by another, more adult name. Instead of John E. Hoover, he became J. Edgar Hoover.

And immediately at 24 years of age, he began creating the Custodial Detention Index, which grew to about 200,000 cards by 1920 and 450,000 by 1921.

This card system was revolutionary at the time, as agents, police forces, governments, and citizens would send information in to the Bureau of Investigation. Hoover had a staff of people who would number each report. Then the staff member would make a card or find an existing card for each person, place, or group mentioned in the report, noting the report number on the card. Any card could then be pulled in every related report along with it and put into a file for review by an investigator.

Congressman Vito Marcantonio called this “Terror by Index Card.”

The card system prevented the errors Francis Bacon identified like the cave by tying together reports and information from different people.

It utilized the cards of Carl Linnaeus and indexing concepts of the Library of Congress and the vertical filing of Melville Dewey.

By 1939, 10 million people were indexed in the system and the Bureau of Investigation got a new title, the FBI.

The End of Cards

The Library of Congress didn’t grow as quickly. It didn’t get to 10 million books by 1939. Though, they were attempting to classify and index everything in the world, not just subversive individuals.

They started with zone Z “Bibliographies” in 1904 and progressed to zone EF, “American History” after that. But would you believe the final classification zone known as KB or “Religious Law” didn’t get finished until 2004, 100 years after they started.

Sadly, it was only 9 years later that the Library of Congress transitioned to online only, relegating the old cards to the basement.

Prior to that, in 1971, a company called the OCLC realized most libraries had the same books, so they started printing the cards for the card catalog to be sent to librarians so they no longer had to write them by hand.

They shipped their final shipment in 2015 to Concordia College and reported they had shipped over 1.9 billion cards.

Whether good or bad, J. Edgar Hoover worked as the director of the FBI for 47 years. All of his work cataloging, indexing, and making cards went away in 2013, the same year as the Library of Congress.

That’s when the FBI also transitioned to the computer as well.

CUTTING ROOM FLOOR

To hear all the stories that hit the cutting room floor, you have to listen to the episode.

ABOUT THE SHOW

Let us tell you the story of the 20th Century, by tracing each event back to the original decisions that shaped it. You’ll quickly find out that everybody and everything is connected. If you thought you understood the 20th Century, you’re in for a treat.

Tracing the Path is inspired by storytellers like Paul Harvey, Charles Kuralt, and Andy Rooney.

INTERCONNECTED EPISODES

|

How a Tennessee Student Overturned the Scopes Trial Verdict Can you believe the 1925 Scopes Trial was undermined by a Tennessee high school senior? |

|

When Osama bin Laden Wrinkled FDR’s Plans FDR made it one his goals to eradicate Polio from the earth. One man put a kink in the plan |

|

The Wizard of Oz’s 30 Year Miracle Beyond every American watching the Wizard Of Oz, this story has ties to Frank Lloyd Wright. |

|

Roald Dahl: The Real Chocolate Spy You probably know about Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Matilda and the Chitty Chitty Bang Bang . . . but you didn’t know this. |

|

How the Oregon Trail Game Made Apple Famous Was it the Apple IIc that made Oregon Trail famous? Or the other way around? |

SEE THE BIBLIOGRAPHY

SUBSCRIBE AND LISTEN (FOR FREE!)

RATINGS & REVIEWS

If you enjoy this podcast, please give it a rating and review.Positive ratings and reviews help bring Tracing The Path to the attention of other history lovers who may not be aware of our show.