Believe it or Not! A Cartoonist Saved our National Anthem

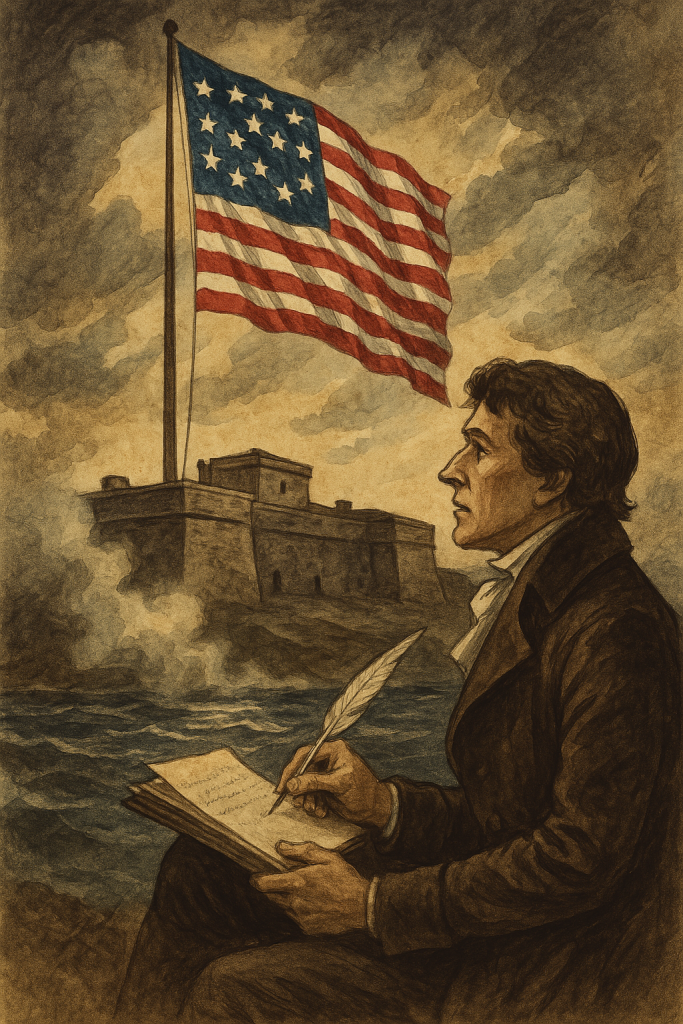

The “Star Spangled Banner” source explores the historical journey of America’s national anthem, tracing its unexpected origins and evolution. It highlights how Francis Scott Key, inspired by the sight of the resilient American flag during the War of 1812, penned the poem “In Defense of McHenry” to the tune of an 18th-century British drinking song, “To Anacreon in Heaven.” The text emphasizes the complex, often controversial figures involved, such as Key, a slave owner who later freed his slaves, and the society that championed the tune’s original form. Ultimately, it reveals how a “Ripley’s Believe It or Not!” cartoon sparked the public push for the song’s official recognition, culminating in its adoption as the national anthem in 1931, a testament to its enduring, albeit complicated, place in American identity.

Audio Hour:

If you run an activity group, classroom or “audio book club”, click here for more information on using Tracing The Path.

Throughout the episodes, every tune is somehow related to the topic. In the Twinkies episode, for instance, the discussion of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops Baseball team concludes with “Take Me Out To the Ballgame”.

How many do you recognize? And harder, how many can you name?

Believe it or Not! A Cartoonist Saved our National Anthem

Since the beginning of America, there have been many troubling times. Times we have all wondered what has become of our nation after this. It happened after the Kansas Nebraska Act opened up the possibility of slavery there. That act would destroy a political party and left America wondering.

When Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, it left the country wondering.

Pearl Harbor brought war to our shores and frightened us.

How would we fight when the enemy came here?

Nixon made decisions that resulted in the resignation of a U.S. president.

The death of Martin Luther King Jr. left African Americans wondering how would their plight go forward. And now the 2020 siege on the Capitol has made everyone see the fragility of our nation.

Back in 1814 at the Battle of Fort McHenry, Francis Scott Key had those same feelings. But then he saw the US flag being hoisted atop a 90-foot pole and wrote down his feelings of resilience and relief in a poem.

How that poem came to be and then how it ever became our national anthem is next. What you’re about to hear has never been heard before.

Anacreon: The Start

Believe it or not, but our story begins in the year 485, with the death of Anacreon, a soon to be lauded poet, in Greece. He had dedicated his life to the arts, and is known for his poems and songs of love, wine, and revelry.

Later, during the Hellenistic period of Mediterranean history, Anacreon was determined to be one of the nine finest poets to have ever written in the Ionic dialect. While not largely studied or famous, one of his poems was set to music in the opera, Don Giovanni.

An Edgar Allan Poe’s poem, The Raven, was largely influenced by his readings of Anacreon. He even cited Anacreon in his poem Romance. He was not the only fan, however.

head of statue of Anacreon

A musician in London in 1776 fancied Anacreon’s drinking songs and started the Gentleman’s Club for amateur musicians called the “Anacreonic Society”. It was for people dedicated to wine and song, and their goal was to advance both.

In fact, in January of 1791, they had classical composer Joseph Hayden as their guest of honor.

Initially, they met at pubs and taverns, but eventually moved to the London coffee house, and then to Crown and Anchor tavern, a bigger place to accommodate their growing group. In 1791, one of the group’s members, John Stafford Smith, wrote an anthem for the group. He titled it “To Anacreon in Heaven.”

At each meeting, after the concert portion was completed, the chairman would sing the song, which opened the evening to more a light-hearted fare, drinking singing songs, singing glaze together. That is until the Duchess of Devonshire attended a meeting in 1792 and left early, denouncing the evening is not fit for women. By the end of that year, the society had folded, leaving the Anacreontic song in its wake.

John Stafford Smith would go on to become a British musicologist, compiling the first collection of English songs in 1779. And he amassed the largest collection of Johann Sebastian Bach’s manuscripts, music and memorabilia.

The Society Across the Pond

Around that time, the Revolutionary War in America had captured the world’s attention. It was America versus Great Britain. Philip Barton Key could only have dreamed of singing glees at a gentleman’s club at the time. Though a Maryland resident, Philip was a loyalist, and thus he was fighting on the side of the British. His battalion was unfortunately captured by the Spanish who were also fighting the British, and they were detained in Havana, Cuba.

At the end of the war he was sent to New York City, where he abruptly left for London. Because, while captive, he had decided he was going to attend Middle Temple in London and become an attorney upon his release. There for two years, Philip got socially connected and spent many of his weekends meeting influencers and attending events, like the ones the Anacreonic Society put on.

In 1785, after having graduated, he returned to Maryland and entered private practice. And that, he turned into becoming a member of the Maryland House of Delegates, their state’s congress, and mayor of Annapolis.

In 1796, Phillips practiced grew when his nephew Francis joined the firm.

Francis Scott Key was born in 1779 to a somewhat British loyal family. While born during the Revolutionary War, by the time he joined Philip, it had been over for 13 years.

Francis grew up on the plantation, Terra Rubra, and was home-educated until he was ten. Terra Rubra was a slaveholders’ plantation. It is unknown how many slaves lived and worked at Terra Rubra, but it is known they lived and worked there until Civil War.

When Francis turned eleven, he attended Annapolis Grammar School, and then later, Saint John’s College, before joining his uncle in the law. Francis would only work there for five years before Uncle Philip was appointed Circuit Court Judge by outgoing President John Adams.

In the following year, he would get married to Mary Taylor Lloyd, the daughter of Edward Lloyd IV of Wye House. Mary grew up at Wye House, which has been described as a 42,000-acre forced labor farm that maintained a thousand slaves.

For two years, Frederick Douglass was one of those slaves.

In fact, later in his life as the famous abolitionist, Frederick wrote about the brutal conditions at Wye House, in his book Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave.

Francis Scott Key

Once married, Francis Scott Key and Mary purchased their first six slaves to work on their farm, and eventually would own 30 slaves once their family grew to 11 children. At the end of President Jefferson’s first term, Philip would leave his judgeship and return to private practice with Francis, where together, they would be part of the famous Aaron Burr conspiracy trial.

Francis did have some other good news that year. His longtime friend, and now famous war hero Stephen Decatur, was returning from his exploits during the Barbary Wars and elsewhere. Stephen had traveled to the Mediterranean as part of the US’s brand new Navy, fighting the Barbers off the coast of Tripoli. There his successes would lead to him commanding the USS Constitution.

The USS Constitution would actually become a famous ship in 1830. A young poet named Oliver Wendell Holmes would read in the paper that Old Iron Sides, as USS Constitution would be called, was to be dismantled by the Navy. Holmes felt that was a very disrespectful demise for a ship that had given so much, so he wrote a poem he titled “Old Iron Sides” that would be published far and wide and we’d lead to the Navy finding new uses for the USS Constitution, saving it from utter demise.

But now, Stephen Decatur was getting married and would be leaving the Constitution for an assignment stateside.

Francis wanted to do something special for his friend. He decided he wanted to dedicate and sing a song to him. One of his favorite tunes that had been passed down by his family was “To Anacreon in Heaven”, that old drinking song from the Anacreonic Society.

To that he penned new lyrics. One of those lyrics was “by the light of our star-spangled flag of our nation”.

That song was enjoyed by all at Stephen’s Welcome Home Gala.

In 1809 James Madison would become president after Thomas Jefferson and would bring America into the War of 1812. Despite the Declaration of Independence in 1776 the British still felt it was their right to come to America, to impress soldiers into their army.

Thus, the War of 1812.

Dr. Beans

During that war, Dr. William Beans was captured by the British. Beans had been a friend of Francis Scott Key and a true patriot. He’d served as a doctor in many battles, including Valley Forge.

He had been captured in DC during the British siege that resulted in the capital and the White House being set on fire. He was also a very influential member of society.

His wife Sarah Hawkins was niece to John Hanson, the president of the Confederate Congress, and for many he was considered the first president of the United States.

Bean’s other friend, President James Madison, would ask Francis Scott Key and another lawyer, Stuart Skinner, to negotiate his release. Francis was a friend and respected attorney, and Stuart already served as the administrator of political prisoners. He and Key would set sail aboard the HMS Minding to the British HMS Tonnant on September 7th to meet with Admiral Cochran and Major General Ross.

It is reported they were treated fairly and after explaining all the good Dr. Bean had accomplished they successfully negotiated his release.

But the British felt Key and Skinner had seen too much of their plans to attack Fort McHenry. So they were told to wait until the task was complete and then they could leave.

On the other side of the harbor at Fort McHenry was Lieutenant Colonel George Armistead. His mission for the last year was to fortify Fort McHenry to be ready at any time. The US felt a loss at Fort McHenry would be a true stronghold for the British, since it would likely mean the British would take over Washington, D.C. and Baltimore.

And Armistead, hearing rumors of an impending attack, since they had just taken D.C., was ready. Nine months prior, Armistead had sent a letter to Major General Sam Smith of the Maryland militia, stating that he was ready, but also saying he didn’t have a banner or a flag to fly over the fort. He requested they send him a banner so big the British could see it all the way to the ocean.

The Young Pickersgill

Commodore Joshua Barney of the militia had a sister-in-law flagmaker. Her name was Mary Young Pickersgill. She grew up in a flag making household, her mother had started. Together with Armistead, they ordered two banners, one to be 17 feet by 25 feet and the other 30 feet by 42 feet.

For Pickersgill, the flags were so large she would need considerable help.

Her family was vehemently against slavery and had several freed slaves as apprentices on staff who would take part. And she invited many others, neighbors and friends would all come together.

Over 200 people would help hand stitch the two flags. They were so large they had to make it at the local brewery, Claggets. Amazingly, Mary conducted her team to finishing the flags in six weeks. They contained over 400 square yards of fabric, weighed 50 pounds, and needed 11 men to raise them atop the 90 foot Fort McHenry Pole.

For this, she would be paid $600.

The 15 stars and 15 stripes would be seen all the way up the Potaspo River.

It was actually the only official 15 striped flag in American history. Two stripes had recently been added for the addition of Vermont and Kentucky, and would only remain the official flag for a few more years. For in 1818, Congress would pass a law standardizing the 13 striped flag.

On September 13th, as rain began to fall, the bombardment commenced. For 25 hours, the British would volley arms at Fort McHenry. Over 2,000 mortise shells were sent. And remarkably, only four American soldiers were killed.

George Armistead, who was one of five brothers in the war, would survive as well.

Key and Skinner could only watch from afar, knowing American defeat would lead to the British taking Baltimore. As nightfall fell in the 25th hour, they had to wait until sunlight to determine the outcome. But at sunset, they could still see a sopping wet American flag sitting still atop the pole.

The Start Spangled Banner

The next morning’s twilight gave proof from the night.

Weighing too much for the pole, Armistead lowered the sopping wet 17×25 foot flag. And to the delight of Francis Scott Key, the 15-starred, 15-striped, 30-foot by 42-foot American banner was raised in its place.

Francis Scott Key writing the Star Spangled Banner

It stirred in Key something patriotic, and in the manner he took to write a song for his friend Stephen Decatur, he penned his thoughts about the stirring moment. He titled it “In Defense of Fort McHenry.”

It carried as much emotion as words could utter.

Upon his return, he made sure everyone at the fort had a copy. And then the Baltimore Patriot and the American Newspapers published it. And a month later, Washington Irving, the editor of the Analectic magazine out of Philly, published it as well.

Francis asked local music store owner Thomas Carr if he would print the words along with the song “To Anacreon in Heaven” for him. On September 20th, Thomas Carr had engraved and printed it and delivered eleven copies back to Francis.

Thomas Carr had titled it “The Star Spangled Banner,” as Key had referred to that in all four verses of his poem.

After the war, Stuart Skinner was appointed Postmaster Baltimore, and later he created American Farmer magazine, the longest running agricultural periodical in the US. He passed away in 1851.

Francis Scott Key would go on to an illustrious law career. He handled the famous Petticoat Affair for the government, and he prosecuted Richard Lawrence for attempting to assassinate President Jackson in 1835.

And he also served as attorney to Texas oilman, Sam Houston.

His stance on slavery would become muddled over the years. In 1830, he freed his slaves, and he began to represent slaves seeking freedom, free of charge, and he represented the estate of John Randolph, which freed over 400 slaves.

He also represented slave Priscilla Queen against the Reverend Francis Neal and her quest for freedom. It was a highly watched case in D.C., because Reverend Francis Neal was the president of Georgetown College. While he became vocal about his opposition to the mistreatment of slaves and was probably against the slave trade, he didn’t believe African Americans could ever live free and equal to whites.

As such, he became a leader of the American Colonization Society. The ACS had started in 1816 by people who felt freed slaves would have more freedom and opportunity if they were back in Africa, where they could create their own society.

They decided to use an American settlement on the west coast of Africa called Liberia and they shipped freed slaves there to live. Britain actually did the same thing, shipping theirs to their settlement called Sierra Leone, if there was any good intent in their heart at all.

Abolitionists like Frederick Douglass spoke vehemently against it, taking people from their home and family and sending them to an unknown world was an act of cruelty, not freedom, he would say. Being a member of the ACS was not the same as fighting for equal rights, and is likely the worst ideal Francis Scott Key held.

Francis’s sister Phoebe Charlton Key would get married in 1806. She married Roger Taney. Roger would go on to become the fifth Supreme Court justice and would serve a long 28 years. Justice Taney’s court heard cases like Marbury vs. Madison and McCullough versus Maryland. And he would also preside over the Dred Scott slavery case, where he would write the majority opinion of holding slavery in the United States.

In the Dred Scott case, the Supreme Court was asked if a freed slave who retained his freedom in Illinois could move to a slave state like Missouri and maintain his free status. However, Roger Taney and the majority of the Supreme Court decided not to rule on that question, but instead argued that a former slave didn’t have the right to sue in Federal Court.

Many believe Taney’s decision, along with the passing of the slavery-friendly Kansas-Nebrask Act, three years prior, led to the formation of the anti-slavery Republican Party, and ultimately the 1860 victory of President Lincoln.

While this is years later, it certainly illustrates the environment Francis Scott Key lived in. Chief Justice Taney’s ruling in the Dred Scott Case and the Kansas Nebraska Act kept race relations on the front door of America.

Oliver Wendell Holmes to the Rescue

In 1861, after Lincoln had been elected President, Oliver Wendell Holmes, our Old Iron Side’s poet, was greatly saddened by the rift in our country over race relations, and he thought it was probably time for another poem. But instead of writing a new poem, Oliver Wendell Holmes penned a fifth verse to Francis Scott Key’s Star Spangled Banner.

It was hope for a coming emancipation.

Holmes wrote,

“By the millions unchained

who our birthright have gained

we will keep her bright

blazing forever unstained.”

That led two years later to Lincoln’s signing the Emancipation Proclamation.

The first time the Star Spangled Banner would receive any official recognition would be in 1897, 54 years after the death of Francis Scott Key. When the U.S. Navy, which was created to fight the Barbary Wars, required it to be played at the retreat and close of parades. Secretary of War Daniel Amont issued the official order during the second term of Grover Cleveland.

That brings us to the next hero of our story.

John Philip Sousa was born before the Lincoln presidency, back in 1854, to a Portuguese father and German mother. He, like John Williams, had a music brain and was a composer at heart.

At 22 years of age, he’d become head of the Marine Band, which would become America’s premier band under his tutelage. In 1886, President Chester Arthur approached Sousa with a request. He didn’t like the presidential song “Hail to the Chief,” and asked Sousa if he’d create another.

In response, Sousa offered up “Semper Fidelis.” However, Chester Arthur didn’t live long enough to hear it. Semper Fidelis would go on to become the official march of the United States Marines.

After leaving the military in 1892, to pursue professional pursuits, John Philip Susso wrote “Stars and Stripes Forever” which would become the official march of the United States.

Through 1900, “The Star-Spangled Banner” hadn’t yet been designated an official song of anything.

That’s where the third hero of our story comes in.

In 1890, Santa Rosa, California, Leroy Robert Ripley was born. His father had died when he was 16, so he dropped out of school and started working at the San Francisco Chronicle as a sports cartoonist.

At 18, he sold his first independent cartoon to Life Magazine, which gave him confidence in his future.

In 1910, San Francisco Chronicle sent him and freelance writer Jack London to Reno, Nevada to cover the fight of the century. Jack Johnson vs. Jim Jeffries. Jack London was 13 years a senior and had 10 novels under his belt, including “Call of the Wild” and “White Fang”.

On that trip, he convinced the young Ripley to move to New York and take a shot at the Big Leagues. And in 1913, Ripley did just that.

Can You Believe it Was Ripley?

He applied and got a job with the New York Globe. A couple of years into the job, he decided to create a panel of cartoons about all the crazy sports feats he’d come across. He’d call it “Chumps and Champs.”

People liked it so much, he did a few more times before deciding to add some non-sports topics, and thus he had to change the name of it. Chumps and Champs didn’t fit when he was talking about non-sports topics. So he changed the name to “Ripley’s, Believe it or Not.”

In 1918, it became a regular column.

William Randolph Hearst, at the time, ran the King Syndicate, which distributed comics and columns to papers everywhere. When he saw what Ripley was doing, he wanted to syndicate it.

He agreed to pay Ripley $1800 a week plus travel expenses and return for syndicating his column. That enabled Ripley to hire a full-time researcher to travel and to think much bigger. Heart financed the trip for Ripley to go to the Olympics in Antwerp Belgium, and a trip around the world in both 1920 and 1922.

The King Syndicate got “Believe It or Not” into 360 papers nationwide, along with “The Amazing Spider-Man”, “Beetle Bailey”, “Betty Boop”, “Flash Gordon”, “Mickey Mouse”, “Mother Goose”, “Popeye”, and “Dennis the Menace” over the years.

There was no better way to get National Exposure.

In late 1929, Ripley heard a rumor. The United States, after 153 years, still had no national anthem.

Thus on November 3rd, 1929, he ran a cartoon saying as much, “Can you believe the USA has no national anthem?”

That fired up the nationwide Veterans of Foreign Wars Organization, who circulated a petition to make “The Star-Spangled Banner” the National Anthem. And they presented to Congress 5 million signatures in 1930.

What Ripley didn’t say was that the US had tried to approve it before. In fact, on six different occasions, as early as 1916, Congressman John Lithicum, from Maryland, had introduced a bill to make The Star Spangled Banner official.

All in all, Congress had considered more than 40 bills to make “The Star-Spangled Banner” the National Anthem, none of them had passed. There was some opposition to the song. Some didn’t like that the tune had been a drinking song, especially after the 1920s when Prohibition went into effect.

Others believed it was too difficult to sing, which seems contradictory to it being a drinking song.

Others didn’t like that the tune was of British origin. Once Great Britain became an ally, some felt it was disrespectful to that relationship. And others thought it ought not be our national anthem at times of peace.

During this time of national debate, Woodrow Wilson had ordered it to be played at military occasions, and he requested the Bureau of Education to arrange the official version of the Star-Spangled Banner.

They, in turn, created a panel of five musicians, led by John Philip Sousa. After seeing the veterans of Foreign War’s petition with five million signatures, John Philip Sousa made his opinion public. The Star-Spangled Banner should be the national anthem.

Later that year, 1931, Herbert Hoover signed into law “The Star-Spangled Banner” as our national anthem.

Sadly, a year later, at the age of 78, John Philip Sousa passed away.

In 1948, under a Presidential Proclamation 2795, Harry S. Truman would designate Fort McHenry as a place that could fly their flag 24 hours a day.

And in 1956, the song was used in Congress as evidence in an effort to make “In God We Trust” the official motto of the U.S. Francis Scott Key has had suggested that in the fourth stanza of the Star Spangled Banner. He wrote,

Then conquer we must,

when our cause it is just,

and this be our motto,

in God as our trust.

And at the 200th anniversary of the Fort McHenry bombardment, a special presentation was made with President Obama in attendance. It was on the west lawn of the US Capitol. “The Star Spangled Banner” that was performed at that ceremony was performed, arranged and conducted by none other than John Williams.

Believe it, or not. “The Star-Spangled Banner” tune was written in the country from which our nation was derived. It was written to capture the emotional site of an American victory. Its lyrics were penned by an imperfect man. It was titled by a small business owner. Its final verse was written by a poet, doctor, abolitionist, and father of a supreme court justice. And the flag it was written about was made by a female-owned business owner who employed freed slaves as apprentices.

It’s America wrapped up in a song, and like everything else will remain controversial as long as there is freedom to disagree.

You’ve been listening to tracing the path with Dan R Morris.

CUTTING ROOM FLOOR

To hear all the stories that hit the cutting room floor, you have to listen to the episode.ABOUT THE SHOW

Let us tell you the story of the 20th Century, by tracing each event back to the original decisions that shaped it. You’ll quickly find out that everybody and everything is connected. If you thought you understood the 20th Century, you’re in for a treat.

Tracing the Path is inspired by storytellers like Paul Harvey, Charles Kuralt, and Andy Rooney.

INTERCONNECTED EPISODES

|

187 Years Behind Martin Luther Kind’s Dream We all learn about the “I Have a Dream” speech, but few know where it comes from. |

|

The Cropduster, The Military Plot and Lindbergh’s 322 bones The world of Lindbergh is wrapped up into so many things. |

|

484 Year Documentary of Muscle Shoals It wasn’t just the music that made it famous? Can you hear Helen Keller? Or see Henry Ford? |

|

Did the East Texas Wildcatters win WWI It was in fact some crazy guys in East Texas that turned the war. |

|

Roald Dahl: The Real Chocolate Spy You probably know about Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Matilda and the Chitty Chitty Bang Bang . . . but you didn’t know this. |

SEE THE BIBLIOGRAPHY

SUBSCRIBE AND LISTEN (FOR FREE!)

RATINGS & REVIEWS

If you enjoy this podcast, please give it a rating and review.Positive ratings and reviews help bring Tracing The Path to the attention of other history lovers who may not be aware of our show.