How the Hostess Twinkie Survived Death (Twice)

This episode tells the complex and seemingly improbable journey behind the creation of iconic American brands like Twinkies and Wonder Bread. It highlights how a series of seemingly unrelated heroes and events, from early baking pioneers like Robert Ward and Alexander Taggart to the invention of sliced bread by Otto Rowetter and the marketing power of Howdy Doody, all had to align perfectly for these brands to emerge and flourish.

The story emphasizes the various challenges faced, including the Great Depression, World War II rationing, and shifts in consumer trends, ultimately detailing how the brands were rebuilt from mere recipes and trademarks after bankruptcy.

The story begins prior to the Civil War, though it doesn’t seem like it could. And amazingly you’ll learn that:

Wonderbread got famous when the commercial bread slicing machine was invented.

Twinkies were created to solve a summer itch.

Howdy Doody actually made them famous.

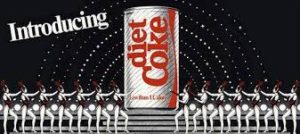

And when someone wasn’t paying attention, Diet Coke crumbled the empire.

Group Leaders:

If you run an activity group, classroom or “audio book club”, click here for more information on using Tracing The Path.

Instructions: Answer each question in 2-3 sentences.

- Who were the Ward brothers and what was their initial contribution to the baking industry?

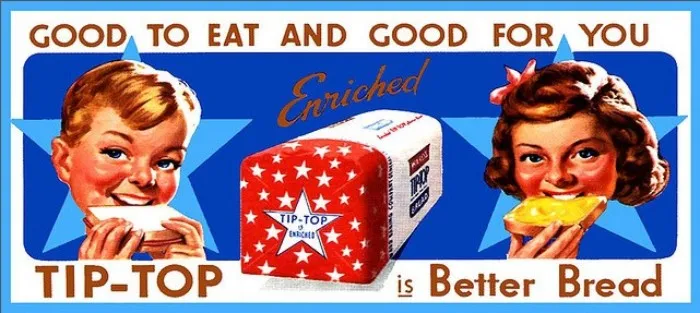

- What was the significance of the Ward brothers’ “Tiptop” bread?

- How did Robert Boyd Ward incorporate his passion for baseball into his bread business?

- What made Alexander Taggart’s “Wonder” bread unique compared to other bread at the time?

- How did Otto Rohwetter’s invention revolutionize the baking industry and impact the sales of Wonder Bread?

- What were the first two five-cent sweets produced by Continental Baking Corporation during the Great Depression?

- What significant event led to the change in the Twinkie recipe from banana to vanilla and extended the product’s shelf life?

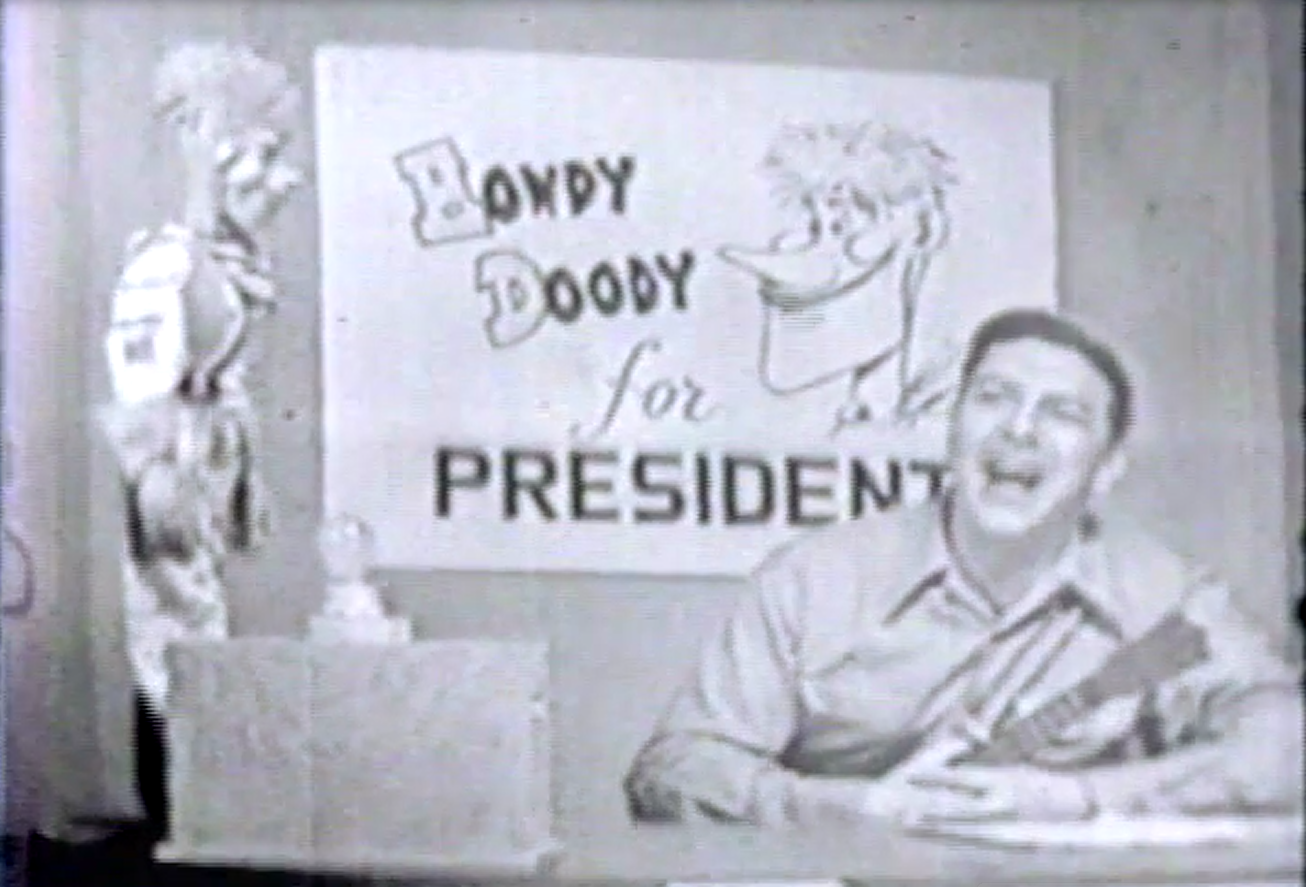

- How did Buffalo Bob Smith and the Howdy Doody show contribute to the success of Wonder Bread and Hostess products?

- What factors contributed to Interstate Bakeries filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2012?

- How did C.D. Metropolis and Apollo Group Management revitalize the Hostess brand after acquiring it?

How Hosted Twinkies Survived Death, Twice,

Typically, it begins with a marble rolling down a track, which runs into a book, and a page opens and pulls a string, and then a domino falls and another marble is pushed, and 48 moves later in a course of about two minutes a Rube-Goldberg machine entertains and creates a furious flurry of domino’s falling.

Well, this is that story.

This is the story of six heroes, and how their convergence created one of the most iconic brands in the world. You’re about to learn about all the Domino’s that had to twist, turn, and fall perfectly, in order to create brands you’ve come to know and love, Twinkies, Hostess, and Wonder Bread.

Twinkies, Hostess, and Wonderbread.

Amazingly, this journey crosses paths with the Major League Baseball, the classic American puppet Howdy Doody, Nabisco, Diet Coke, and World War II. It took a lot of research to figure out all these pieces put together, because what you’re about to hear is unknown to everyone listening.

This is the 2nd edition of Tracing The Path.

WONDER BREAD

I struggled where to begin this story because 1863, where I need to draw you the first picture, is just so long ago. Our first hero, Robert Boyd Ward, was eight at the time. His father owned a bakery outside of Pittsburgh and due to Civil War labor shortages, little Robert was taught to bake cakes and hand deliver them to customers, sometimes two miles away.

As he grew up, baking became his passion. When he and his brother William were old enough, his father gave them $300 to start their own bakery. And in 1878, Ward Bakers was born.

The Ward Brothers revolutionized baking. They tasted everything, and were very in tune with the economic climate and with their price-sensitive customer base. They were the first to grind wheat into five different layers, testing every combination possible to create the most efficient white and wheat loaves.

They actually found a way to make a two pound loaf of bread for the same cost as one pound loaf. They called this jumbo loaf bread “Tip-Top”. It was the first of its kind. They opened shops from Chicago to New York and Tip-Top bread became the US’s number one selling bread.

By 1913, they had factories in six cities and produced 249 million loaves annually. That same year, Robert Ward, who was a big baseball fan, got involved with the short-lived Federal League of Baseball, and bought the Brooklyn Tip-Tops. Always wary of people harpooning his intent, he tried everything to make sure people knew he wasn’t using baseball to promote his bread, but rather using his bread to promote baseball.

His best idea that grew his bread business even more was to put Tip-Top baseball cards into each loaf of bread. Unfortunately, the Federal League only lasted two years, leaving only the Chicago Cubs as a Wrigley Field as the last reminder.

Sadly, Robert didn’t even make it to the last game. He died suddenly in 1915, leaving his bread empire to his brother William.

Over the next five years, William continued to modernize and grow, helping to reach Robert’s dream of a bread manufactured from start to finish without touching human hands. William grew the business rapidly. He acquired many small bakeries, and he even changed the name to Continental Baking Corp (for the bulk of its existence, most people refer to it as CBC.)

Let’s briefly leave our first two heroes, Robert and William, and introduce our third.

TAGGART BAKING

Alexander Taggart was a young man in 1867 when his family arrived in the U.S. from the Isle of Man near the United Kingdom. His father, a baker, had had enough of the local political turmoil there and moved the family to Indianapolis. To carry on the family tradition, he would have to start working in bakeries right away. When he finally realized he wanted his own baker, he joined forces with a local baker and started Parrot-Taggart Baking Company.

And in just about a decade, the two hardest working bakers were acquired by a larger, more aggressive bakery (which in the course of three years had acquired 114 other bakeries.) It was called the National Biscuit Company, which you now know as Nabisco.

It only took Alexander a few short years to realize he wanted to leave the National Buscuit Company and start his own company again, so he left and started a new company, Taggart Baking Company.

And within a few years became the largest baker in Indiana, selling 300,000 loaves per week. In addition to bread, he sold sweet crackers and cakes too, and just like Robert and William Ward, Alexander strived for immaculate conditions, and a bread also untouched by human hands.

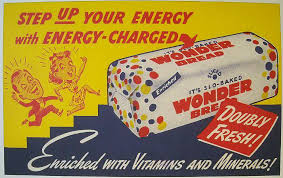

He even painted everything in the factory’s white, including the ovens. Then in 1921, they had a breakthrough. All their testing created a bread that had a soft crust, a creamy white interior, and didn’t crumble when it was buttered. They named the bread Wonder. They dropped all mention of homemade bread, put red yellow and blue circles on the bag, and told people, “It was better than anything you could make at home.”

His goal was to make factory bread, he desired an alternative to homemade.

And just like Tip-Top, they sold a 1.5 pound loaf of bread for the same price as the one pound loaf. Wonder Bread would only be sold at Indiana for its first four years until it caught the eye of William Ward.

And in 1925 our heroes come together.

SLICED BREAD

Continental Baking Corporation bought Alexander’s Taggart Bakery. To the chagrin of CBC, Wonderbread didn’t take off right away, but when William Ward met Otto Rowetter, the game changed.

Otto Rowetter was a doctor of optics who chose jewelry over optometry as a career. While he lived and grew up in the grain belt, by 1910, he owned three jewelry stores in St. Joseph, Missouri.

Being very mechanically minded, he spent a lot of time in his basement tinkering with inventions. It is unclear what drove his big project, but he believed in it so much he sold his jewelry stores to work on it. And for the next 11 years, his invention would suffer incredible setbacks, like bankruptcy and fire.

In fact, once a fire destroyed all of his equipment and blueprints, making him start over from scratch for memory. But in 1927 his dream became a reality. He had invented the first commercial bread slicer.

For a company like CBC, that meant an entire loaf of bread could be evenly sliced and wrapped for the consumer.

In 1930 it caught the attention of William Ward and CBC and the first mass-produced sliced bread made its way to store shelves and sales of the 1.5 pound loaf of Wonderbread skyrocketed, with a new tagline “Greatest Thing Since Sliced Bread.”

Within three years, 80% of all American bread sold would be pre-sliced.

(And as a side note, “Which came first? Sliced Bread or Pop-up Toasters?” Surprisingly, the Pop-up Toaster was invented in 1919 by Charles Wright, a friend of Otto Rowetter, but he would have to wait 11 years for sales of his pop-up toaster to take off. It wasn’t until Otto Roebter and the uniform slicing machine changed bread and the world forever.)

HOSTESS TWINKIES

Sweetcrackers, Shortcake, Strawberry Shortcake, Tip Top Red and Wonder Bread dominated the CBC product offering. But with the 1929 Great Depression underway, they wanted to also produce 5 cent sweets. The first was a cream-filled chocolate cupcake. They called it the Hostess Cupcake.

And wanting to use the off-season strawberry shortcake pans, they created a cream-filled banana cake they dubbed the Hostess Twinkie. Both sold very well in the post depression market.

But CBC had a problem. The real bananas, real cream, and freshness of Wonder Bread meant their products only had a two-day shelf life. That wasn’t enough for a 300-mile truckload, let alone the warehouse.

That all changed in 1941 when the United States Government enacted food rationing before World War II. Among other things, bananas, sliced bread, and sugar were all rationed forcing CBC to make changes.

Banana Twinkies became vanilla.

Real ingredients gave way to substitutes.

And CBC grew their shelf life to 12 days, which meant they could reach more stores.

And Vanilla Twinkies were a bigger hit than the banana ones. CBC even employed Louis Prima’s 1923 song, “Yes, We Have No Bananas” to sell even more Twinkies.

The post-war years were very good for Hostess, with more money in hand and soldiers returning, everyone was looking for sweets to eat.

HOWDY DOODY

That brings us to our sixth hero, Bob Smith.

In 1947, across the country in Buffalo, New York, a young Bob Smith was entertaining audiences for WNBC radio. His skills at piano, guitar, screenwriting, comedy, and skits led NBC to offer him a chance to do a kids program on TV.

TV was the most exciting thing to happen to entertainment since, well, since the radio. And Bob Smith had never had opportunity to be on it, and he wanted to put on a really good show for the kids. Thinking back to his radio show, he recalled how many of his listeners had commented on how they love the character, Elmer, a country-westered character he’d used to start each of his shows.

So he made a western looking puppet and named him Howdy Doody. And then on December 22nd, 1947, magically timed, with thousands and thousands of new Christmas TVs, Buffalo Bob Smith and Howdy Doody took the airwaves by storm.

They were an instant phenomenon.

A few days later, 1948 began an election year. Dewey, Truman and Thurmond had thrown their hats in the ring, but neither understood the power of TV.

Bob Smith thought it would be fun to get the kids involved, so on their 8th episode he announced Howdy Doody was also running for president. Just to test audience response, he asked the kids to send him a postcard, listing what important things he should be running for President to do.

In exchange, the kids would get a campaign button, so NBC ordered 5,000 “Howdy Doody for President” campaign buttons. And to their astonishment, 30,000 letters came in in week 1, and then 30,000 more in week 2. 30,000 more in week three. And by the time it was over 150,000 letters came in, and sponsors took note.

It was unlike anything NBC had ever seen before. Offers came in from everywhere to license products, advertise, and sell Howdy Doody puppets. It was unheard of.

And Howdy Doody became the first show to be fully sponsored two years in advance. And who was the title sponsor? Continental Baking Company.

They decided how did he do the would be a perfect selling tool for Wonderbread and Hostess products.

At the end of each show for 14 years, Buffalo Bob Smith would tell the kids to ask their parents to put Wonderbread and Hostess Snacks in their lunchbox. Hostess and Wonderbread became household names with Twinkies leading the charge.

Twinkies place in Americana would continue to grow, but not necessarily the success of CBC.

In 1968, international telephone and telegraph, ITT, bought CBC, which was unusual, but they owned a lot of unusual things, like a Nazi munitions manufacturer, Focke Wulf, and Sheraton Hotels, And they actually use their eclectic mix of companies as a weapon against their rival GTE.

They sued GTE for buying companies that actually made sense in an antitrust suit, but they lost. But can you believe a few short years later, the FTC cracked down on International Telephone & Telegraph when they started buying too many bakeries?

By 1984, with CBC sales passing $1 billion. They were sold to Ralston, for $475 million. And then 10 years later, flipped to Interstate Bakeries for $560 million, making it the largest bakery in the world.

At 58 factories, 1250 outlet stores, and 10,500 delivery routes. Twinkies were now a part of the American fabric. Even Jimmy Carter installed a Twinkie vending machine in the White House. Archie Bunker had demanded them in his lunch. Diehard, Ghostbusters and the Simpsons all showed Twinkies. And in 1999, Bill Clinton put them in the 100-year United States official time capsule.

Unfortunately, while riding the pop culture wave, ITT, Ralston, and Interstate Bakeries weren’t paying attention to the health revolution. Starting in 1976, Larry Gross’s Billboard #1 hit, “Junk Food Junkie” kicked off a change in America. That song spurned Roger Benotti, a science teacher at George Stevens Academy in Blue Hill, Maine, to put a twinkie in a glass box to see how long it would take to break down. All the signs were there.

In 1977, Slim Fast hit the market.

In 1979, Dexatrim.

Also in 1979, Dan White, who was on trial for the murder of the San Francisco Mayor, tried to use junk food as his murder defense.

In 1982, Jane Fonda’s workouts hit the scene.

And in 1983, Diet Coke exploded on the scene and became the number four top-selling soda in its first year.

That’s the year Interstate Bakeries paid $560 million for CBC.

By 2012, it was too late. Interstate Bakeries had grown to 18,000 employees, 10,000 vehicles, 260 properties, 372 different Union contracts, while sales of Hostess products dwindled to only $36 million.

Their a lack of attention to consumer trends, finally caught up to them. A host of bad business decisions prevented them from lowering costs. They tried to organize many times, but in 2012 they filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy as the only remaining option.

And Hostess was gone. The 87-year marriage of Taggart’s Wonder Bread and Ward’s Tip-Top Bread was over.

A company named Hilco Global was hired to manage the sale and dissolution. They sold Wonder Bread for $355 million to Flower Foods. Flower already owned Dave’s Killer Bread and Tasty Cake, Sunbeam, Earth Grains and Canyon Bakehouse. So they were able to get Wonderbread back on the shelves quickly.

Hostess, however, was put out to bid separately, and companies all over the world were rumored to be putting in a bid. But only one company did.

C. Dean Metropolis was a turnaround expert, some have called him Mr. Schilf’s base. He had previously revitalized to Pabst Blue Ribbon, Vlassic Pickles, Bumblebee-Tuna, Chef Boyardee, and Pam Cooking Spray. And though he might not have known it, his life had touched CBC once before.

Back when ITT sued GTE for breaking anti-trust laws, C. Dean Metropolis worked at GTE. But now, teamed up with Apollo Group Management. Their $410 million winning bid got them the Hostess brand, the recipe cards, and five factories.

But unlike Flower Foods, they had no distribution. This was almost starting from scratch.

Dean and Apollo knew they weren’t buying a company. They were buying an iconic brand with a hundred year history that needed tweaking, and they were the specialists to do it.

According to Dean, they had one problem to solve, shelf life. While it been a long-running joke that Twinkie’s lasted forever, previous owners were only able to manufacture a 25-day shelf life, which meant distribution by warehouse was never an option.

So, Dean hired professionals and altered the recipe until they achieved a 65-day shelf-life. First problem solved.

This solution meant the treats could be sent directly to a warehouse from the factory, eliminating 20,000 delivery trucks. Then, harking back to the days of Taggart and Ward, they installed a 20 million dollar auto-bake hands-off system in their Emporia Kansas factory. And now, a 500 person plant producing 1 million Twinkies per day does what 14 plants and 9,000 workers did just three months earlier.

Stores were so excited to get Hostess back on the shelves, they ignored slotting fees, and with the new Warehouse Distribution Strategy, Dean and Apollo expanded Hostess’s platform from 50,000 stores to 210,000 stores, and in just four short months.

Hostess was back on shelves.

C. Dean Metropolis said, “I knew we had a hit when I saw Al Roker tossing Twinkies to the crowd from a San Francisco cable car on the Today Show.”

The Hostess brand in its 100 year history was so strong that being stripped all the way down to trademarks and recipes cards wasn’t going to stop it.

New flavors, tie-ins, products and sales, sky-rocketed Hostess. C. Dean Metropolis and Apollo spent $410 million to buy Hostess and another $290 million rejuvenating it.

But in two years they were able to sell it for what the brand was really worth. $2.3 billion. Unfortunately, Robert and William Ward, Alexander Taggart, Otto Rowetter, and Bob Smith, weren’t around to see it.

You can, however, see the 1976 Twinkie still in a box in Blue Hill, Maine. And just like a Rube Goldberg machine, there is no particular domino or marble that actually stands out. Without all of them, without every fall and tumble, you have an entirely different story.

Welcome to “Tracing the Path.”

CUTTING ROOM FLOOR

To hear all the stories that hit the cutting room floor, you have to listen to the episode.

ABOUT THE SHOW

Let us tell you the story of the 20th Century, by tracing each event back to the original decisions that shaped it. You’ll quickly find out that everybody and everything is connected. If you thought you understood the 20th Century, you’re in for a treat.

Tracing the Path is inspired by storytellers like Paul Harvey, Charles Kuralt, and Andy Rooney.

INTERCONNECTED EPISODES

|

How many times has Coca-Cola Changed the Recipe? Coke Classic was one, right? But did they really change it back to the original? |

|

How Negro League Baseball Solved the Cuban Missile Crisis It was bittersweet to see the Negro League end. So many goods, so many bads. |

|

The History and Impact of McCann Erickson You’ll be amazed at how many things in our world come back to McCann. |

SEE THE BIBLIOGRAPHY

SUBSCRIBE AND LISTEN (FOR FREE!)

RATINGS & REVIEWS

If you enjoy this podcast, please give it a rating and review.Positive ratings and reviews help bring Tracing The Path to the attention of other history lovers who may not be aware of our show.