Why Rand McNally’s Route 66 Started With Camels

This episode traces the fascinating history of Route 66, highlighting the contributions of various individuals and organizations that paved the way for modern American highways. Starting with Edward Fitzgerald Beale’s early survey using camels, the text explains the growing need for better roads due to the popularity of bicycles and later, automobiles, leading to the formation of the Good Roads Movement and the creation of named trails by automobile clubs. The pivotal role of Rand McNally in developing uniform road numbering and signage is detailed, culminating in the government’s adoption of a national highway system in 1926, which included Route 66, initially numbered US 60. Finally, the source touches on Route 66’s significance during the Dust Bowl migration and its eventual decommissioning due to the rise of interstates, while also noting ongoing efforts to preserve its legacy.

Audio Hour:

If you run an activity group, classroom or “audio book club”, click here for more information on using Tracing The Path.

Throughout the episodes, every tune is somehow related to the topic. In the Twinkies episode, for instance, the discussion of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops Baseball team concludes with “Take Me Out To the Ballgame”.

How many do you recognize? And harder, how many can you name?

Why Rand McNally’s Route 66 Started With Camels

Most people follow the path laid out by those who came before them. But when there wasn’t anyone who came before, you become the trailblazer. Today’s story celebrates trailblazers and the full circle that comes from their lead. We’re about to trace the intersecting paths of Charles Lindbergh, Rand McNally, the Indianapolis 500, and more.

Our story starts with Edward Fitzgerald Beale, a man whose story is a movie unto itself. Born to a metal of valor winner from the War of 1812, Ed’s military and retirement life is nothing short of extraordinary.

President Andrew Jackson appointed him to Philadelphia Naval School. He was present at the annexation of Texas. He worked alongside Kit Carson in the Mexican-American War. And he served as a spy, reporting directly to President Polk.

President Fillmore appointed him superintendent of Indian Affairs. President Lincoln appointed him Surveyor General of California, and President Grant made him the U.S. Ambassador to Austria.

Edward Fitzgerald Beale.

But Edward’s greatest impact started in 1857.

Already retired from the Navy, President Buchanan appointed him to survey a 1,049 mile trail from Fort Smith, Arkansas to the California border. It would be the shortest, flatest trail to the west, and Ed was asked to do it, not with horses, but with a camel brigade, to see if they would be more efficient and helpful than America’s horses.

It is this path he blazed that we build the rest of this story.

The wagon road, Ed surveyed while flat, was still dirt and hard for anything to traverse, other than horses and camels. But pressure started to mount for smoother surfaces.

In the 1880s, bicycles started to get very popular, and bicyclists needed better roads. The dirt ruts for carriages were hard on bikes. Bikes clubs from all over met in Newport, Rhode Island, and began the Good Roads Movement. They called themselves the League of American Wheelmen and produced a magazine that reached a million people.

Only a year later, Charles Duryea produced the first gas-powered vehicle, and it wasn’t long before the first automobile organization started. Over 600 towns by 1895 had automobiles, according to Horseless Age magazine, and by 1900, over 8,000 horseless carriages existed in the US.

Beyond their need for just smooth riding surfaces, all these bicycles and automobiles created the need for defined paths of travel and maps as well. And the automobile groups obliged by creating their own named trails.

They’d find a series of dirt roads between two places, create the directions to follow that path, and would give the root a name, and then share that with their members. Oftentimes they’d paint an arrow on a rock or a pole along the way with the trail name. But this rogue volunteer-based system of creating name trails wasn’t very efficient. And the names they came up with weren’t very helpful.

Names like National Old Trails Road, Old Spanish Trail, Great Dirt Road and Salt Trail. Without communication between the trail clubs, many of the trails overlapped. Going across the state of Kansas, you could take the Atlanta Pacific Highway, National Old Trails Road, the National Roosevelt Midland Trail, the Pike’s Peak Ocean to Ocean Highway, the Union Pacific Highway, or the Victory Highway, you can all be on the same road.

Self-interest also added to the inefficiency. For instance, the state of Utah helped promote the Arrowhead Trail from Salt Lake to LA over the shorter trails, as Arrowhead kept drivers in Utah longer.

So in 1903, the system was tested.

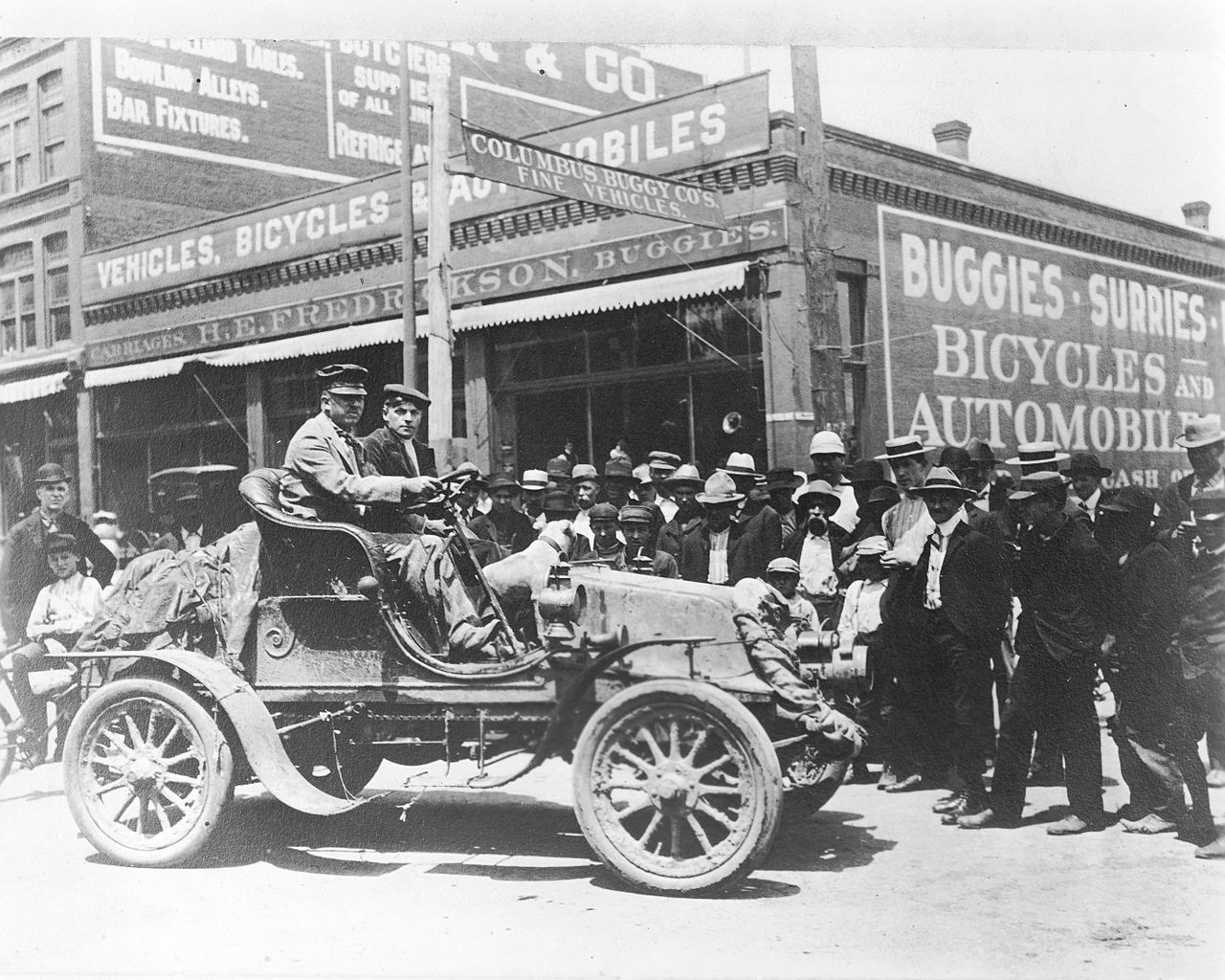

Horatio Nelson Jackson accepted a $50 wager to see if an automobile could make it across the country. He had no car to his name, but he found a Wynton car and a willing mechanic, Sewall Crocker, to make the trip. It took 63 days and 800 gallons of gas. They broke down many times, got stuck and broke parts, but they made it. Horatio Nelson Jackson and Sue Crowder became the first people to cross the United States in an automobile.

And it wasn’t until 1908 that the Model T4 hit the American roads.

By 1910, US roads would carry over 1 million cars. While there were only 2.4 million miles of roads at this point, only 3,000 of them, mostly in cities, were paved. The government was really feeling the pressure of managing roads.

That year, their informal office of road inquiry officially became part of the Department of Agriculture as the American Association of Highway Improvement. Despite the government’s best intentions, the people are always faster and more innovative.

Carl Fisher, a wealthy businessman in Indiana, wanted to create a paved place for car enthusiasts to race. And without anyone else doing it, he thought he should probably do it himself. So he created the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 1909 and convinced investors to spend $3.2 million to pave it with bricks, which is why it became known as the Brickyard. It opened May 30th, 1911, with 80,000 people paying a dollar each to watch the first Indy 500.

Carl and two friends, Frank Seavrly, of Goodyear Tire and Henry Joy of Packard Motors, conceived of creating a highway that would take drivers from Times Square to New York to Lincoln Park San Francisco. In 1913, they charted this road, named this 3,389 mile road, the Lincoln Highway, and sent word to auto clubs everywhere.

It became the first national memorial to honor Lincoln, and would soon be dubbed America’s Main Street. In 1915, they created another one called the Dixie Highway, taking people from a Milwaukee to Miami. And thus an ocean to ocean and north to South Highway had been born.

Incidentally, Carl would eventually move from Indianapolis to Miami via the Dixie Highway. He would find a great area just south of Miami that looked perfect. He had the area dredged to make a bigger beach, engineered plans for roads to it and settled, and is known today as the man who built Miami Beach.

That brings us to the next hero of our story.

A year before Edward Fitzgerald Beale began surveying his thousand mile road, William H. Rand, and Andrew McNally, opened a print shop in Chicago. Their main client was printing tickets and timetables for Chicago’s railroads.

In 1871, the Chicago fire would threaten their business, and in an almost mythical tale, they buried two of their printing machines in sand before evacuating their building. After the fire, they dug up their equipment and were up and running in two days.

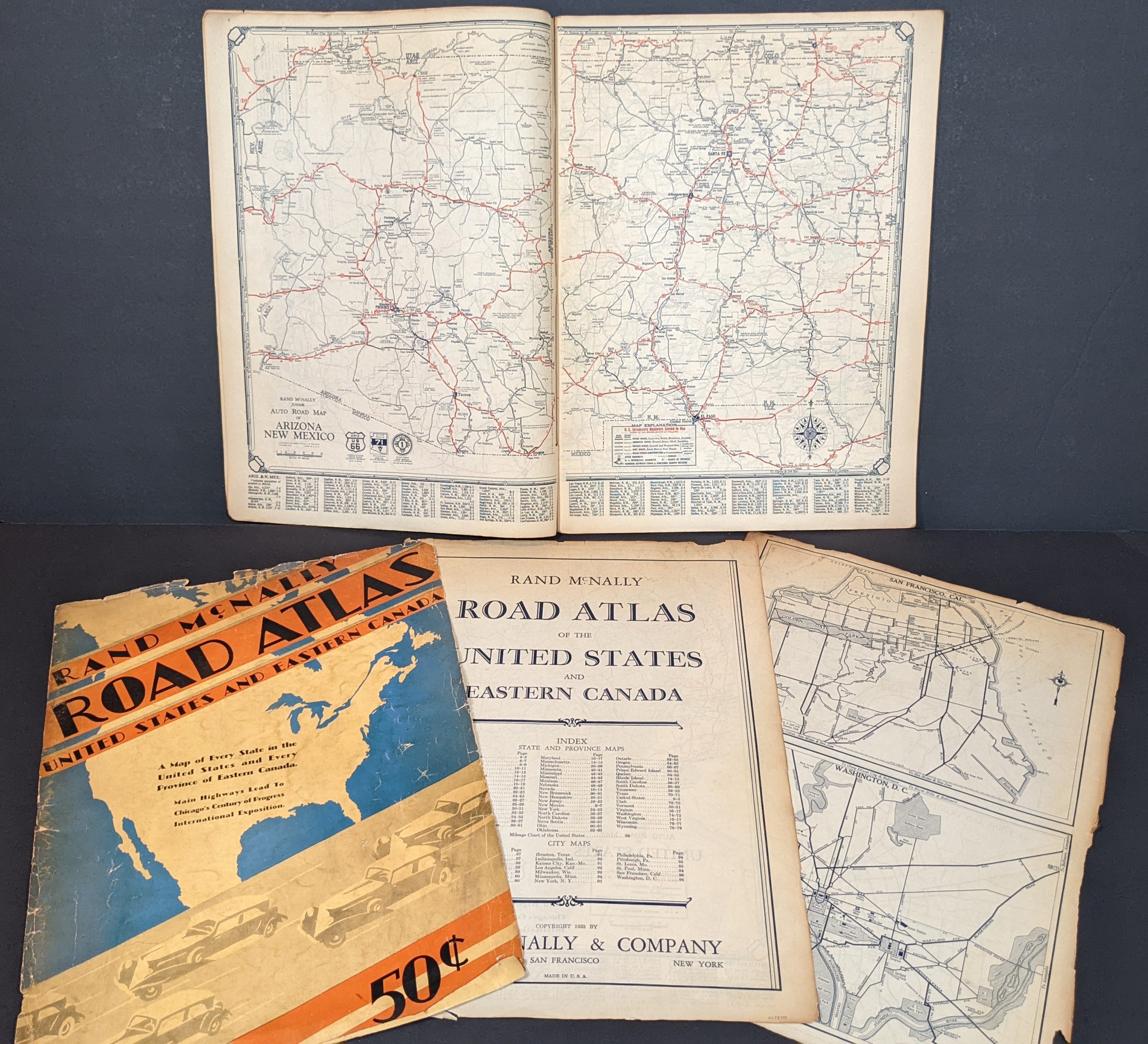

In 1872, they’d print their first map, a railroad guide. The first road map, however, wouldn’t be printed until 1904, but not by Rand McNally.

Early Rand McNally Roadmap

Charles Howard Gillette, an oil lubricant salesman, felt his customers could use a map, but he didn’t really have the money to print very many. So he thought he’d get a sponsor. Just two years prior, in 1902, he became the secretary of his auto club, the American Association of Autumn Wheels, or AAA. They decided to advertise on his map, which gave Charles the money for greater distribution.

And in 1913, the year the Lincoln Highway was dedicated, golf oil opened their first drive and gas station in Pittsburgh, and they to decided to print and hand out maps to customers. They gave out so many maps, they had to turn the business over to another mapmaker, the Automobile Blue Book Company.

And by now maps had changed permanently.

Gone were topographic features, streams and important landmarks. Now they were just city names connected by lines, some unnamed and some with very long names. Rand and McNally were sad to see the beauty of maps disappearing. And also wanted maps to be more helpful to drivers since there was little connection between the map and the real world. Drivers would encounter roads not on the map, would not know if they were at the intersection they needed to be, or at an intersection not shown on the map.

Rand and McNally knew there had to be a better way. In 1915, they decided to offer their employees and consultants $100 to whomever came up with the best plan for a new map concept. Freelance Map Illustrator John Garrett-Frank answered the call.

John’s idea was revolutionizing, and it started with the words “When the world doesn’t fit the map, change the world.” At first his idea was simple and logical. Add a legend to the map, with street names listed alphabetically and assigned a number to each name. Then label that road with the number, saving infinite amount of space on the map itself, so they could add features, plus the ability to sell advertising.

A gas station, for instance, could have their location on the map. That solved the map problem, but John wanted to solve the real life problem. The second part of his suggestion was that they go out and actually mark the roads with the street numbers. He wanted a uniform black square with white painted numbers.

Rand McNally loved his idea and wanted to do it in a small city to start with. So they chose nearby Peoria, Illinois. They created the Peoria map and then with the help of auto clubs marked all the roads with the uniform sign. And Peoria was just the first of many.

Soon cities were being redrawn everywhere. On a vacation trip even, John Brink marked the 180-mile Ohio, Indiana, Michigan way, all by himself. Everyone wanted their town or road blazed by Rand McNally. To achieve wider reach, Rand McNally partnered with Auto Clubs, State Highway Departments and Utility Companies everywhere.

In some cases they designed and manufactured the necessary signs and stencils. Other times they put together a crew and sometimes they financed the trailblazing.

In 1919 New York State bought 50,000 signs. And two years later, Gulf Oil, who’d switched to another mapmaker, switched to using Rand McNally maps at all their stations.

By 1926, Brink estimated they had erected 1 million signs, blazing 50,000 miles of road. The government’s plan wasn’t quite as swift.

While Rand McNally had 50,000 miles under its belt by 1926, the government wouldn’t have made a single decision by then. Back in 1916, President Wilson signed the Federal Aid Road Act because he wanted to connect the farmers to the cities and improve the roads for military purposes.

It was the first federal funds for highway improvements. 75 million was appropriated to be spent over five years. But World War I slowed progress of the 522 earmarked projects leaving only 17 miles to have been improved.

After World War I, it became clear to the Army that an infrastructure needed to exist for security purposes to transport troops and heavy vehicles across the continent. So in 1919 they commissioned an army convoy to go from DC to San Francisco. 100 vehicles, heavy troop carriers, light trucks, jeeps, field kitchens, and one tank. The going was rough.

It took them 61 days to cross the Lincoln Highway. They experienced over 200 accidents, 150 vehicle failures, 21 injuries, 88 bridge repairs, and lots of roads not strong enough to carry the load.

The convoy had one special passenger, Lieutenant Colonel Dwight Eisenhower. Eisenhower reported to the Secretary of Agriculture that the named Road Trail System wasn’t working. The dirt roads weren’t reliable and a national solution needed to be considered.

The State Highway Department’s concurred and created for themselves a national association to come up with a national solution. The first thing they were able to decide in 1923 was a set of standardized road signs. Brown would be warnings, black railroad crossings, rectangles would be regulatory, octagons would be stop signs, diamonds for yielding, and squares would be caution.

They also decided on the shield system. Interstate roads would be indicated by a white US shield with a black border and the black painted road number in the middle. They’d let the individual states decide if the state name or the letters US would get written at the top.

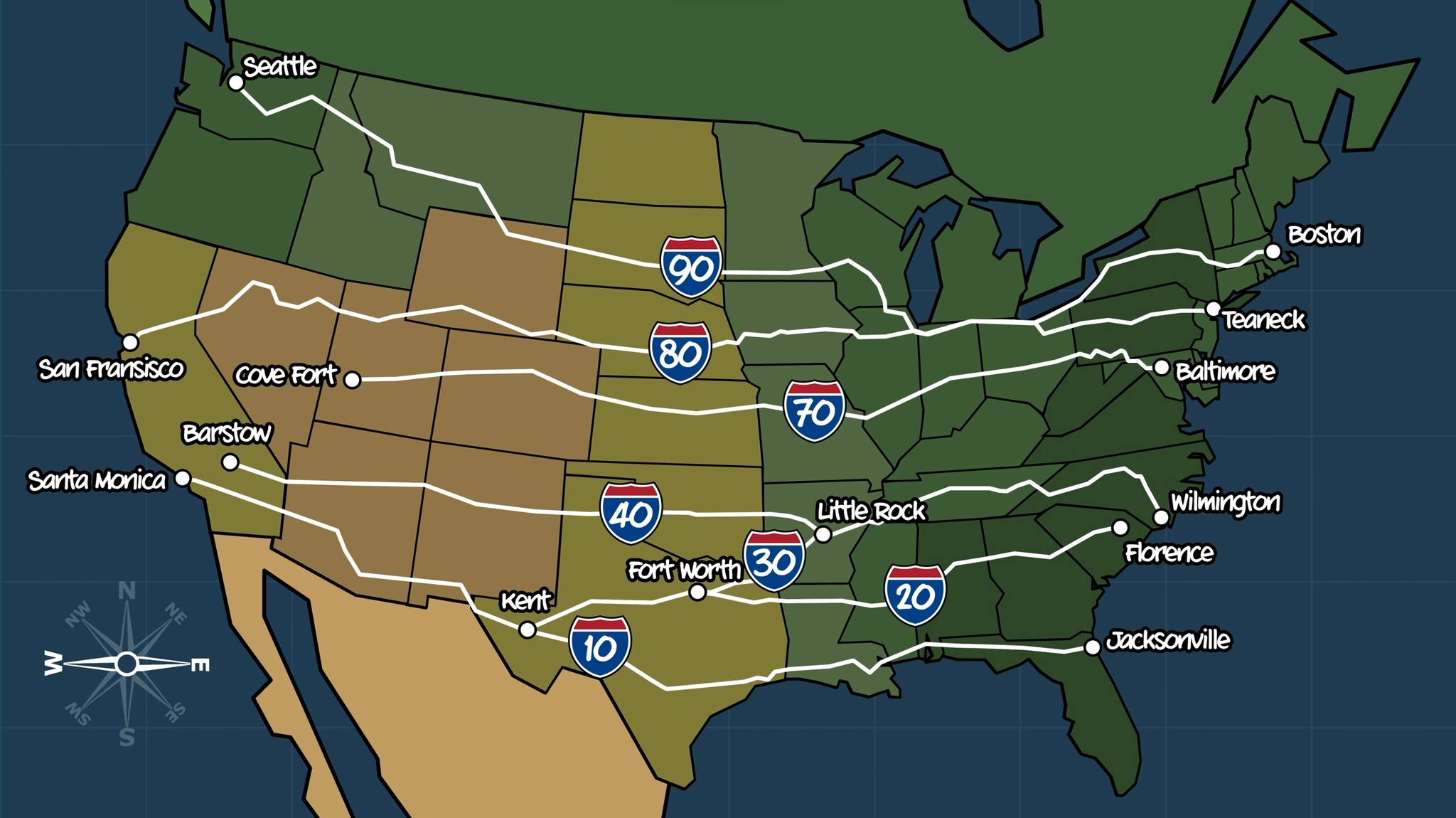

In 1925, they contacted John Brink of Rand McNally to get help on the numbering system. He explained his process and then together they decided east-west roads would end in zero, rising in number from south to the north, and the north-south roads would end in one and five, allowing for further expansion. The U.S. government formally made the new system official in 1926, making some, maybe all, of Rand McNally’s signs instantly obsolete.

Even numbered highways go east-west

And that brings us back to Edward Fitzgerald Beale.

The thousand-mile path that President Buchanan had asked him to survey, was part of the government’s highway map. After surveying that route, part of it was used for the transcontinental railway, for the Santa Fe Railway and for the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. And now it was part of a highway stretching from Chicago to Los Angeles, marked US60 on the government map. Of all the new US highways, this road truly connected the farmers of America’s heartland.

Cyrus Avery was the Oklahoma State Highway Commissioner at the time, as well as a realtor and a businessman, he needed roads personally to get to all his properties and badly wanted the roads for his state’s farmers. He was so excited to get the new road, he printed 60,000 brochures about the road and the small towns it touched.

The people of Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska were special. Most had arrived (or had parents who arrived) because of the Homestead Acts. The Homestead Act of 1862, the Kinkaid Act of 1904, and the Endangered Homestead Act of 1909. All promising settlers, hundreds of acres of land. Over 3 million people from the Eastern US and Europe alike flooded the great plains looking for new opportunities.

And when the end of World War I came, it saw the price of wheat skyrocket. Homesteaders were eager to plow the prairie grasses and make way for crops. This new national road would enable them to get their crops to market faster. And that’s what Cyrus Avery was excited about.

But Cyrus printed his brochures too early because “official” didn’t mean “official”. A few states had things to work out and a couple had problems. One of those changes came from Kentucky. They wanted U.S. 60 to go through their state and lobbied for the Virginia Beach to Springfield, Missouri portion, be called 60.

Many compromises were attempted and solutions offered. In the end, it was decided that the Virginia Beach side, being named U.S. 60, leaving Chicago to LA, nameless.

That left Cyrus with 60,000 brochures he couldn’t use. Without recourse, he looked at the numbers not yet used. He wanted his state to have a round memorable number, but there were no numbers ending in zero remaining. But 66 was left on the page. So the road Edward Beale and a pack of camels held build would become the most famous road in the world on April 30th 1926.

It would become Route 66.

That left Cyrus with one goal, get it paved. He worked tirelessly to get Route 66 paved. One of their more famous ventures to draw attention to their cause was convincing CC Pyle, a sports promoter, to stage a foot race from New York to LA, following Route 66. At the time, CC Pyle represented football player Red Grange and luckily for Cyrus, CC’s American football league had only lasted one year, so he was ready for a new venture.

The race was dubbed “The Bunyan Derby” and featured 199 runners taking off from LA. CC drove a mobile broadcasting truck and had celebrities like Will Rogers meeting the runners along the route. Cyrus also took an ad out on the Saturday evening post inviting America to take Route 66 to LA for the 1932 Olympics.

Because of his efforts, Route 66 was the first highway to be completely paved.

But that wasn’t until 1938, four years after the largest migration in US history began. While the Homestead Acts brought people to the Midwest, the 1929 Depression was the first swipe at driving them away. The Depression reduced the wheat prices, leaving farmers with acres of dirt. And then in 1931, drought hit.

Massive dust storms began. The dust storms referred to as blackout blizzards” killed people, crops, and farm animals. The worst dust storm occurred on April 14, 1935, leading an Associated Press reporter to coin the term “the Dust Bowl.”

During the 1930 to 1940 Dust Bowl years, 3.5 million people migrated out of the Midwest. Many headed to California on Route 66. One of those travelers was author John Steinbeck, who wrote about the plight in his 1939 book The Grapes of Wrath, dubbing Route 66, the Mother Road. Steinbeck was merely the first to land mystique to the road.

Dorothea Lange, a photographer, took amazing photos of the Dust Bowl migration, and those photos too were shown in museums around the world.

Charles Lindbergh made some of the cities on Route 66 stops for his transcontinental air transport company. He even designed an airport along Route 66 in Kingman, Arizona and showed up with Amelia Earhart to dedicate it.

In 1956, President Dwight Eisenhower, former member of the 1919 Army convoy, signed the Federal Highway Act, which led to the end of Route 66. Bigger, more modern roads were built nearby, leading to the decommissioning of it in 1984.

Today, the Route 66 corridor preservation program helps keep the focus on Route 66 raising money to keep America’s road great. In fact, in 2003, famed radio personality Paul Harvey sent a thousand dollars to Vernell’s motel outside of Raleigh, Missouri to help repair their sign.

And in a full circle moment, the Adventure Cycling Association has the goal of getting America back on bicycles again, including staging bike tours of Route 66, which you can do now with step-by-step map directions on the Phios 85 handlebar GPS unit powered by Rand McNally.

CUTTING ROOM FLOOR

To hear all the stories that hit the cutting room floor, you have to listen to the episode.

ABOUT THE SHOW

Let us tell you the story of the 20th Century, by tracing each event back to the original decisions that shaped it. You’ll quickly find out that everybody and everything is connected. If you thought you understood the 20th Century, you’re in for a treat.

Tracing the Path is inspired by storytellers like Paul Harvey, Charles Kuralt, and Andy Rooney.

INTERCONNECTED EPISODES

|

The Surprising Life Story of Paul Harvey Pearl Harbor, Pilot, Chicago and Coca-Cola; The World’s Most Prolific Radio Man |

|

Roald Dahl: The Real Chocolate Spy You probably know about Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Matilda and the Chitty Chitty Bang Bang . . . but you didn’t know this. |

|

The Cropduster, The Military Plot and Lindbergh’s 322 bones The world of Lindbergh is wrapped up into so many things. |

|

The Wizard of Oz’s 30 Year Miracle Beyond every American watching the Wizard Of Oz, this story has ties to Frank Lloyd Wright. |

|

The Cheesy Results of WWII Is it possible that the whole reason we have nachos is because of WWII?? |

|

She Bombed the President for Votes Women, who were given freedom by the Constitution spent 200 years fighting to use it. |

SEE THE BIBLIOGRAPHY

SUBSCRIBE AND LISTEN (FOR FREE!)

RATINGS & REVIEWS

If you enjoy this podcast, please give it a rating and review.Positive ratings and reviews help bring Tracing The Path to the attention of other history lovers who may not be aware of our show.