TRACING THE PATH PODCAST

How Many Times Has Coca-Cola Changed Their Secret Recipe?

This episode details the evolution of Coca-Cola’s secret formula and brand identity, showcasing how external factors repeatedly shaped its trajectory. It begins by recounting the 19th-century French wine blight, which spurred the creation of Angelo Mariani’s Vin Mariani, a coca-infused wine that served as a precursor.

The story then shifts to John Pemberton’s development of Coca-Cola in response to the temperance movement in Atlanta, highlighting the crucial shift from wine to carbonated water and the initial inclusion of coca leaf extract.

Subsequent changes to the formula, such as the removal of cocaine in 1903 and the adjustment for kosher certification, underscore the company’s adaptability and commitment to maintaining its trade secret, even at the cost of entering or staying in certain markets.

Finally, the episode touches on the introduction of diet drinks like Tab and Diet Coke, the infamous “New Coke” debacle, and the eventual substitution of high-fructose corn syrup, illustrating Coca-Cola’s continuous efforts to innovate and respond to consumer preferences and economic pressures while fiercely guarding its core product.

Audio Hour:

If you run an activity group, classroom or “audio book club”, click here for more information on using Tracing The Path.

Throughout the episodes, every tune is somehow related to the topic. In the Twinkies episode, for instance, the discussion of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops Baseball team concludes with “Take Me Out To the Ballgame”.

How many do you recognize? And harder, how many can you name?

The Wine of Coke

It is said three people can keep a secret, as long as two of them are dead. But there is a secret that has successfully been hidden for over a hundred years. The secret has been kept so well, most don’t know it has changed at least five times.

And very few know about the final change.

In the 1890s, the bull weevil crossed the border from Mexico and wreaked havoc on the cotton industry in the American south. And the phoenix that rose from the ashes was both the jobs that moved north and the rise of the peanut farmer.

But it wasn’t the first plague to first decimate an industry then give rise to another. In fact, it was forty years prior that French winemakers experienced the same kind of invasion. Only this time, the invasion came from America, and this time, they didn’t know they hadn’t invited it.

French wine makers in the 1850s wanted to experiment with American grapevines, so vines were imported. However, the possibility of transporting invasive damaging pests wasn’t considered, and thus the Phylloxera aphid arrived in France.

In a funny reverse of technology making life better sort of way, it was the invention of the steamship that made the aphid invasion possible. Just a few years prior, and the aphids would not have survived the long trip. Steamships made their survival possible.

Sadly, grapevines and France were not naturally resistant to the aphids, and the great French wine blight of the 19th century began.

Over 40% of the French grapes and vineyards were devastated over 15 years from the 1850s to the 1870s. The French economy was hit hard.

Many businesses were lost and wages in the wine industry were cut in half. The price of wine then rose as the supply was cut, and French drinking customs changed, moving towards spirits and absinth.

French culture believed in the health benefits of red wine for longevity and overall well-being. Thus, the search for healthy alternatives began, which brings us to the first hero of our story, Angelo Marioni.

Angela was born on December 17, 1838, to a family of wealthy doctors in Corsica. When he was 20, he moved to Paris to work as a chemist, and became intrigued with studies he’d been reading on coca leaves.

Coca leaves dated back 3000 BC, more widely used by the South American civilizations, like the Incas. It was often chewed like tobacco, which gave the chewer a bit of a high. It also had been used medicinally and as a numbing agent.

As the French wine culture moved further and further away from wine, wine got cheaper. It was inexpensive enough it afforded Angelo Mariani the chance to experiment with coco leaves steeped in Bordeaux Wine to create a new medicinal drink.

Angelo called it “Vin Tonique.” It was immediately applauded as a stomach stimulant and an analgesic on the airway passages and the vocal cords. Many found it to be an appetite’s present and an antidepressant as well.

Its medicinal properties were a combination of the resveratrol in the wine and the six milligrams of a coca alkaloid in each ounce. It wouldn’t be until later that the COCA alkaloid was given the name “Cocaine”.

Angelo’s Vin Tonique was lauded all over the world by Kings, Queens, popes and presidents. President McKinley, Thomas Edison, Alexander Dumas, Jules Verne, H. G. Wells, Emil Zola, Algoost Rodan, Henrik Ebsen, amongst many others, all applauded Angelo Mariani’s Vin Tonique.

Angelo did not ever share the full secret recipe for his Vin Tonique, but people all over the world attempted to make their own. Which brings us to the second hero of our story.

Pemberton’s Vin Tonique

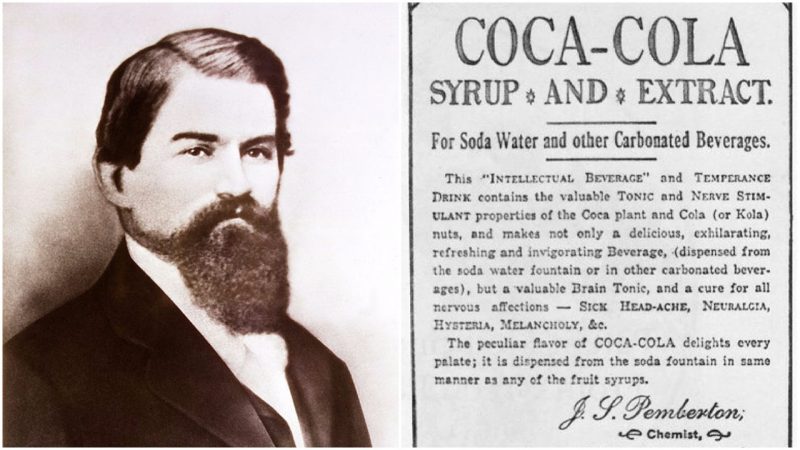

Mr. John Pemberton, living across the Atlantic and the United States. Pemberton was a few years older than Angelo, and like Angelo, he had become a chemist.

Unfortunately, his career took a detour in 1861 when he joined the 12th Cavalry of Regiment of the Confederate Army in the U.S. Civil War. Pemberton was wounded in the Battle of Columbus, the last true battle of the Civil War, and managing his wounds he subsequently became dependent on morphine.

His story wasn’t unique, however.

The conclusion of the Civil War brought on a demand for herbal and patent medicines as thousands returned home with lingering injuries.

Pemberton returned to his pharmacy and began his work as a chemist, looking for pain relief. He was also fascinated in particular by the effects of coco leaves, and Angelo’s Vin Tonique de coca.

Pemberton decided to do some experimenting with his own, with alcohol and coco leaves, adding in the African kola nut for flavor. When he was satisfied with his concoction, he named it Pemberton’s French Wine Coca.

But the cultural environment in Georgia were Pemberton lived, put his project somewhat in jeopardy. There were growing movements pushing for both the prohibition of alcohol and a nationwide awakening to the addictive effects of the cocaine in coca leaves.

Atlanta, where Pemberton’s pharmacy was located, was having its own Civil War, except this wasn’t a north and south issue, which takes us back to 1836 when the Georgia General Assembly voted to build a railroad from Savannah to the U.S. Midwest.

They first planned to build from the Chattanooga, Tennessee to the middle of Chattahoochie. Surveyors picked a place where the first part of the railroad would end, which became known as Terminus. It wouldn’t be until many years later that it would be named Atlanta after the western Atlantic Railway.

Atlanta’s first mayor was Moses Formalt, a stillmaker, owner of Mirell’s Rose Saloon, and a member of the “Free and Rowdy Party”. The salooned sympathetic rowdies saw drinking and merriment as an essential part of urban life. They were strongly opposed by the Moral Party of Temperance-minded Evangelical Protestants who wanted to eradicate drinking, prostitution, and other things they labeled as sins.

So the battle lines were drawn.

And in 1885, the showdown happened.

An election was held between the wet and dry factions. And when the results were tallied by a very narrow margin, Atlanta became the first big city to go dry, prohibiting alcohol. But like the French wine blight, prohibition meant the demand for tonics and carbonated beverages grew quickly.

So naturally, Pemberton changed his recipe, substituting carbonated water for wine. But taking out the wine left the concoction bitter. All in all, he combined:

coca leaves, kola nut, glycerin, water, lime juice, vanilla, caramel, orange oil, lemon oil, nutmeg oil, Coriander, Noreoli, and Cinnamon to make his new drink. He’d also had a bit of alcohol in it, but that was burned off in production.

With the end of saloons and bars, drug stores and soda fountains became the new social hub and gathering place. He uses his own drugstore to test out his new tonic, and as partner Fred suggested he name it “Coca-Cola.” Since he was using “Coca leaves” and the African “Kola Nut,” except for one change, he thought spelling “Kola” with a “C” instead of a “K” would make it look better for advertising purposes.

Their first year, 1887, they sold 990 gallons of this Coca-Cola syrup to soda shops for a profit of $510.

But the very next year, Pemberton became ill. Not able to see the future of his wonderful Cola recipe, he began selling rights to the formula to help pay for his medication. One of the two people he sold rights to was Asa Candler, another Atlanta pharmacist. And after Pemberton’s death in in 1888 and for about $300, Asa Candler became the owner of Coca-Cola and would go on to grow Coca-Cola immensely.

The Candler Trade Secret

Part of growing the brand was trademarking the Civilian script written logo and protecting the formula.

Prohibition in Atlanta only lasted a couple of years. And after that, Candler had to protect his syrup from the high taxes that were put on alcohol. So to to differentiate the barrels themselves from barrels of alcohol, Coca-Cola’s syrup was transported in brightly red painted barrels.

And to protect the secret recipe, Candler had two options:

1. He could patent their creation, or

2. He could declare the recipe a business asset and label it a trade secret.

While a patent does give enforceable government protection, it also requires disclosing the recipe in a public filing, and then when the patent expires, it becomes free for all to use. So he chose Trade Secret and made sure no one had access to it.

Keeping his secret also meant that he could change it or alter it, which Coca-Cola would eventually do five times over the next hundred years.

His biggest risk then was someone reverse engineering the syrup or someone else leaking it.

Selling the syrup to soda fountains didn’t come with a lot of risk, but as more businesses wanted to carry it, he was confronted with the idea of bottling it.

In Vicksburg, Mississippi, for example, a candy store owner wanted to sell it, but he didn’t have a fountain. So he actually ordered the syrup and bottled it himself in traditional Hutchinson’s bottles, the kind you would normally associate with the milkman.

And even grocery stores like Claude Hampton’s, who had been buying it for their soda fountain, wanted to sell it in bottles. But it wouldn’t be for another five years that Candler would strike a bottling deal.

1898 would bring on a new problem for Candler.

The December 12th issue of the Los Angeles Herald appeared the title, The Cocaine Monster. The article indicated that the use of cocaine had quadrupled in the previous five years and the numbers of the addicted had skyrocketed.

For Coca-Cola and Candler, the Coca Leaf Extract provided the drink provided great benefits, with the resulting Cocaine alkaloid being way too little to make a difference. The cocaine the article referred to had been extracted and powdered, which was much different.

Cocaine was still being sold over the counter. In fact, the Sears and Roebuck catalog contained Peruvian wine of cocoa and Rhino’s Hay Fever potent, which was 99.9% cocaine. Nevertheless, to be safe and avoid future government regulation, in 1903, Candler began removing the coca-alkaloid from the leaves before using them in the cola.

Forever leaving, the history of cocaine in Coca-Cola far, far behind.

Branding the Giant

The first time the secret recipe for coca-cola had changed was when they removed the alcohol and substituted with carbonate water.

Now removing the Coca Alkaloid from the Coca-Cola was the second change to the secret recipe.

Three years later in 1906, Upton Sinclair’s book The Jungle was published, causing public outrage over food degredation and unsatisfactory practices in the food industry. That caused the federal government quickly passed the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, which prohibited the sale of drugs in interstate commerce.

Thus, Coca-Cola was three years ahead.

Over the next few years, Candler put Coca-Cola in every corner of the country. It had become a national phenomenon.

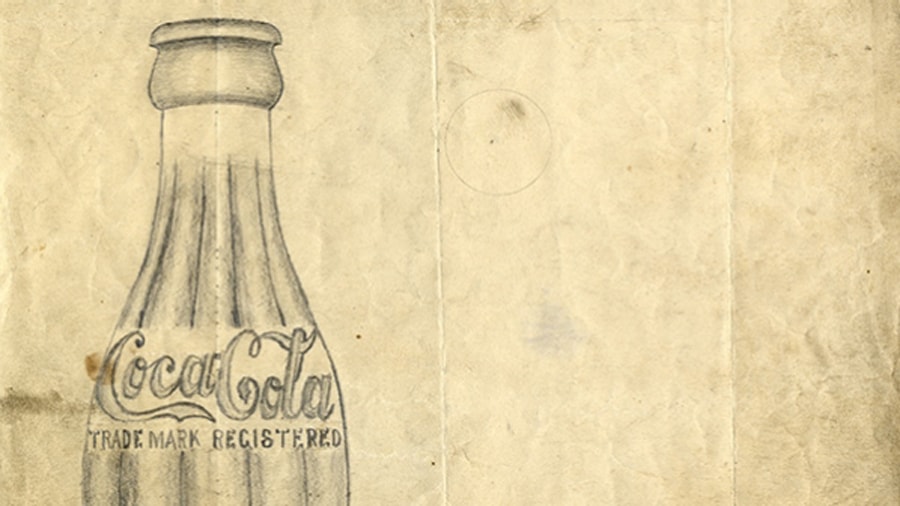

In 1914, along with the proprietary formula, the trademark name and the brand-identifying red-colored barrels, they thought it was time Coca-Cola had a unique bottle as well. So, Candler sent out a plea to all the bottlers that they rally behind getting a new and distinctive bottle.

Coca-Cola then set aside $500 to create a prototype design. Ten glass companies received a challenge to create a bottle so unique you would recognize it by feel and if it was just broken pieces on the street.

The Root Glass Company in Terre Haute, Indiana stepped up to the plate. Alexander Samuelsson was the shop foreman, who sent two people to the library to research this “coca leaf” and this “African Kola nut”.

But at the library they couldn’t find anything. What they did find, however, were pictures of the cocoa bean, the bean responsible for chocolate.

The beans elongated ribs were exactly what they were looking for. They sketched out an inspired bottled design and struck four samples.

And in 1916, a committee composed of “bottlers” and Coca-Cola Company officials overwhelmingly chose “Root’s design” as the new Coca-Cola bottle.

The Root Glass company filed for a patent on a bottle leaving out Coca-Cola’s name for secrecy and then contracted with six-class companies to make the bottles. The bottles were to be German green, which Coca-Cola later renamed Georgia Green.

And since the bottle was a bit more expensive, it was hard at first to get all the bottlers on board. It was difficult because Coca-Cola had spent all their time, marketing Coca-Cola as a five-cent drink.

To get all the bottlers to use the bottle, they started featuring the green Coca-Cola bottle on the advertising as well. Still promising, it would only be one nickel.

The Kosher Side of Coca-Cola

At the age of 68, Asa Candler was ready to retire.

He had purchased the Coca-Cola recipe for $300 in 1888 and was prepared to sell the company now. On September 12th, 1919, he sold it to Atlanta businessman Ernest Woodruff for $25 million.

Ernest had founded the Atlantic and Edward Street Railroad early on in his career and spent 20 years as president of the Trust Company, which is now Suntrust Bank.

His purchase of Coca-Cola was his biggest achievement to date, but his helm would be challenged immediately. Public pressure over crime and its relationships to drugs was increasing. Cocaine itself was already banned, but in 1922 the Jones Miller-Narcotics drug import and export pact banned the importation of coca leaves, one of Coca-Cola’s main ingredients.

The government granted permission to a few companies to continue importing the coca leaf as long as they removed the coca and destroyed it. Woodruff immediately lobbied for the right to create a business relationship with one of these companies.

That 1922 arrangement he made with Maywood Chemical Works still exists today.

Having spent his entire career working in the trenches, in 1923 he decided to give the helm of Coca-Cola to his son Robert, which then flourished under his leadership with high standards, quality and service.

In 1926 Robert Woodruff established a foreign department which opened the world’s doors to Coke. They built plants in France, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Belgium, Italy, and South Africa.

And in 1928 he became the first and lead sponsor of the Olympics, exposing Coca-Cola to people from all over the globe. Woodruff didn’t have any challenges to the secret formula of Coca-Cola until 1935, and that’s when he met to Bias Giffin.

Tobias had been born in Lithuania in 1870. Through his Jewish faith, he’d been a rabbi there, and in New York City, and in 1910 moved to Atlanta. In Atlanta, he’d organized the first Hebrew school and standardized the regulation of kosher supervision all across Atlanta.

His proximity to Coca-Cola’s headquarters meant he fielded many questions about the kosher nature of Coca-Cola. So Rabbi Gefan asked Coca-Cola if he could see the secret recipe in order to confirm and announce that it was Kosher, and Coca-Cola obliged as long as he agreed to never disclose what he learned.

Gefan discovered that Coca-Cola was not indeed kosher.

The glycerin ingredient was produced from the tallow of non-Kosher beef. For Passover, Jews are not permitted to consume products derived from grain, which that little bit of alcohol did.

So for the third time, Coca-Cola changed its formula.

This time to a vegetable-based glycerin, and a sweetener to replace the alcohol made from cane and beets.

And with that, Rabbi Gefan issued a response link that Coca-Cola was kosher for year-round consumption.

Coca-Cola During WWII

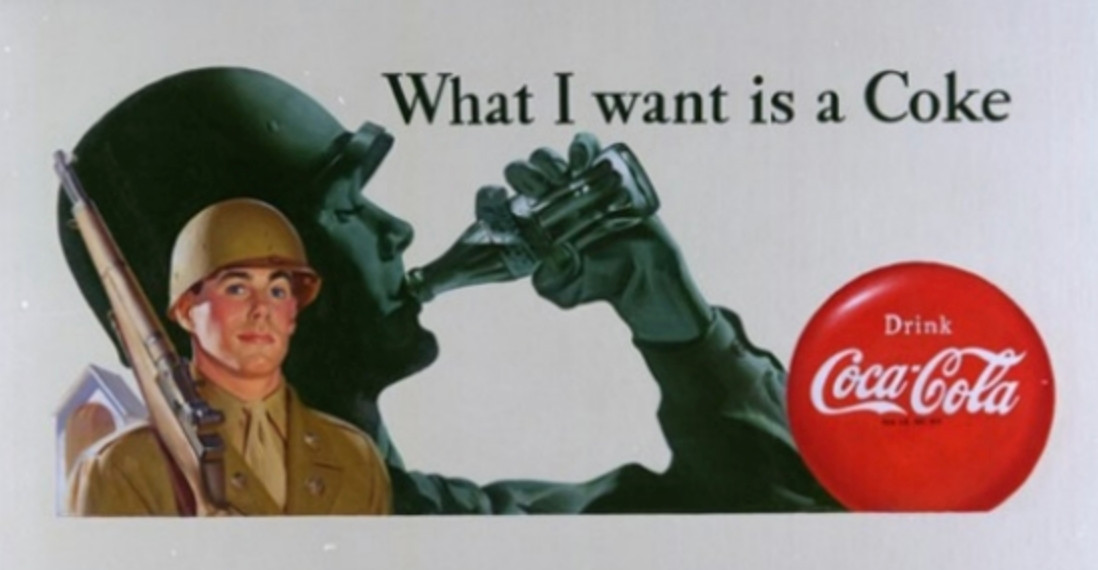

World War II would be coke’s next biggest test.

Woodruff would face sugar rationing, ingredient shortages, and logistical challenges. But World War II would be the single best time in Coca-Cola’s history.

Coca-Cola’s global expansion would be the first hurdle. Getting the ingredients to countries affected by war would require cooperation from every country’s staff. However for many countries the 1917 Trading with the Enemy Act, passed after WWI, would become insurmountable. Doing business with enemy nations had to stop.

Max Keith was in charge of Coca-Cola’s operations in Germany, and realized he would be out of business if he didn’t come up with another plan. They didn’t have Coca-Cola syrup, and because of the 1917 Trading with the Enemy Act, they weren’t going to be getting anymore. But they had everything else they needed to make soda.

His team rallied with the plan of making their own soda from the ingredients available to them, which was mostly food industry extras like discarded apple pulp. So they quickly formulated a new recipe that looked like ginger ale but tasted more like cola.

And deciding what to name their new drink, Max challenged the team to choose any name they could think of in their wildest fantasy. And in that moment they realized fantasy itself sounded like a good name. Didn’t look right on the label though with so many letters, so they changed it.

They shortened it to Fanta.

Fanta would become Coca-Cola’s second brand as it had quickly become the number one selling soda in Germany.

At home, the government-mandated sugar rationing was specifically targeted to non-essential foods like Coca-Cola and Twinkies. In fighting the rationing order, Coca-Cola had an unlikely supporter, General Dwight T. Eisenhower, and many others in the Army.

Eisenhower was in command of troops in North Africa. It was important for him to keep up the energy and morale of our troops. He had seen on many outgoing postcards written to loved ones that soldiers wrote one of the things they were fighting for was the right in freedom to drink Coca-Cola.

On January 28, 1945, Eisenhower asked the government for a rationing exemption to be made for Coke. Because he wanted enough equipment, bottles and Coke syrup, adequate to supply six million servings per month to the troops.

And he wasn’t the only one.

An officer of the 55th Infantry Exchange pleaded with his suppliers. He said,

“Unless we get more Coca-Cola, we’ll have to admit defeat at the hands of the enemy, heat and thirst. The army has already been schooled to like and want Coca-Cola, because Coca-Cola is the wholesome quenchie drink. And I ask you, representing 4,000 Coca-Cola drinkers that are supplied be multiplied by 10 and even more if possible.”

And the government conceded, giving Coca-Cola an exemption from the sugar rationing order.

When Coca-Cola left India

At the conclusion of World War II, as the world’s new country borders were being decided, and life was getting to a new normal, the UK didn’t have the resources to manage the complete British Empire.

As such, places like India that had been clamoring for independence were given it.

For the US, it all meant markets previously operated, controlled by the British Empire, were now available. Coca-Cola wasted no time moving into New Delhi right away.

But India’s independence left the government wanting to push local businesses over foreign companies. That feeling became an undercurrent of Indian politics, many using Coca-Cola as the example. That feeling carried all the way through to 1971 when Indira Gandhi was elected Prime Minister on the platform of eliminating poverty.

One of her first actions was initiating “FERA” the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act. Through that new law, foreign subsidiaries were to reduce their ownership of the local assets to 40 percent, giving Indian people and companies 60 percent.

Coca-Cola was fine transferring ownership, as long as it maintained complete control of the quality and the syrup. The Indian government said, “No.” They felt ownership meant local owners had access to the technical specs and knowledge.

Coca-Cola and Woodruff would have to decide if a market of 651.7 million people was worth sharing their trade secret.

So in 1979, Coca-Cola packed their bags and went home.

Keeping the trade secret was worth more than 651.7 million new customers. Besides, Coca-Cola had Coke, Fanta, and one other soda to grow at home, which takes us back a few years to 1903.

The Scramble for Coke

Back in 1903, when bottled Coca-Cola was catching on, Claude Hatcher was the grocery store who was buying it for a soda fountain, but he wanted this soda in bottles. He had purchased so much syrup he thought he should be getting a discount, but Coca-Cola said no.

Disgrunted by that decision, he declared he’d never buy Coca-Cola syrup again, but would instead formulate his own cola.

So he launched Union bottling works in the family grocery store and produced Royal Crown Ginger Ale in 1905, followed by a drink called Ne-hi, and finally in 1934 R.C. Cola.

Hatcher didn’t have the reach of Coca-Cola, but he was the first to sell soda in cans.

And in 1955, he would launch a soda that would forever alter the direction of Coca-Cola. 1955 was shortly after World War II and was a time of great prosperity and affluence, and with that came a surge in obesity.

You could see in advertisements and fashion there was a general awareness of weight and a new desire to be thin. Hatcher wanted to be part of that solution and looked for a way to sweeten his soda without calories.

With Cyclemate and Saccharin, he launched Diet Rite, which became the fourth best-selling soda in 1962, cutting into Coca-Cola’s profits. The allure of this new health-conscious consumer caught Coca-Cola’s attention.

From the outset, creating a new drink was a massive endeavor, and for Coca-Cola, uncertain of the cultural future, they didn’t want to malign their flagship drink in any way. They felt like calling their soda sugar-free or diet would somehow conversely paint a negative picture of Coca-Cola.

So they took a revolutionary approach.

They used an IBM 1401 computer to generate a list of 4,000 four letter words that had only one vowel. And from that, they scoured for a word that would appeal to women, not be trademarked, and fit the brand of Coca-Cola.

The word they found was T-A-B-B, which they then further shortened to T-A-B. It was great for people who wanted to keep tabs on their health. They packaged it in a pink can and marketed it to women as a soda for beautiful people.

Tab, only one calorie.

In the 1970s, Tab became a great investment for Coca-Cola.

The effects of the 1950 Cuba Revolution were reverberating across the globe. After the revolution, as a response to Fidel Castro, the US banned imports from Cuba, which hurt US businesses like Coca-Cola, because Cuba’s biggest export was sugar.

Russia then decided to buy all of Cuba’s extra sugar and hoard it for themselves, causing the price of sugar to skyrocket. For Coca-Cola, Tab, which didn’t rely on sugar, could be profitable, where Coca-Cola was losing profit due to rising sugar prices.

Coca-Cola knew it could combat the high price of sugar by changing out the sugar in Coca-Cola for high fructose corn syrup, but that would mean changing the secret formula and slightly altering the taste.

Robert Woodruff used his influence to say no to that.

Coca-Cola did in fact allow a few bottlers, who had big problems, substitute 50% of the sugar for corn syrup, but they did not make the change. By the 80s, Coca-Cola wanted to introduce another drink based on artificial sweeteners. They had determined two things to be true.

Marketing Tab to women left men without a solid choice.

And they didn’t have a no-calorie option for Coca-Cola’s flavor profile. And so, in 1983, they debuted Diet Coke, to which it became number one selling soft-drink worldwide.

For the flagship drink Coca-Cola, however, Diet Coke had cut into market share, and their biggest competitor Pepsi had cut into sales by focusing its marketing on grocery stores. The perfect storm was forming for Coca-Cola.

Leadership at Coca-Cola was beginning to sense a change needed to be made. Robert Woodruff’s influence would be coming to an end sadly, while he had successfully taken Coca-Cola to global a juggernaut, and through World War II, he passed on operational control in 1955 and had since been part of the board.

Under his leadership, the secret formula had not been compromised or reduced in value.

In 1984 he stepped down from the board, giving then current CEO Robert Goizueta opportunity to chart a path of his own. Under Goizueta Coca-Cola shared with the world that private taste tests had concluded culture preferred something sweeter.

And with that knowledge, they had formulated a better, rounder, bolder, and more harmonious new Coca-Cola.

And then, in April of 1985, 48 days after Robert Woodruff passed away, Goizueta introduced a new and improved Coca-Cola.

This would be the fourth change to Pemberton’s original formula. While some consider the move, the biggest marketing debacle of the 20th century, others contend Goizueta’s plan was brilliant.

I’m sure 1-800-get-Coke received 400,000 calls from angry coke fans who wanted the old formula back. But the Coca-Cola news also completely dominated the evening news cycle.

Comedians, talk show hosts, NPR, newspapers, magazines, and even a baseless class action lawsuit brought Coca-Cola attention it had never seen.

And then finally, America’s most famous newsman Paul Harvey gave an impassioned plea for Coke to bring the old formula back.

New Coke lasted 79 days and when the announcement broke, daytime television was interrupted. Peter Jennings would break the news to America that old Coke would return. But unbeknownst to the world, Coca-Cola would make the fifth and final change to the top secret recipe.

To avoid the high price fluctuations of sugar, Coke classic, without mention, substituted high fructose corn syrup for sugar. Coca-Cola has changed its formula at least five times since John Pemberton.

And Coke has added a variety of flavors and beverages to its offering. With few people remembering the nostalgic days of World War II and fewer the days of Coca-Cola Classic, will there be enough nostalgia to keep Coke’s formula the same forever?

CUTTING ROOM FLOOR

To hear all the stories that hit the cutting room floor, you have to listen to the episode.

ABOUT THE SHOW

Let us tell you the story of the 20th Century, by tracing each event back to the original decisions that shaped it. You’ll quickly find out that everybody and everything is connected. If you thought you understood the 20th Century, you’re in for a treat.

Tracing the Path is inspired by storytellers like Paul Harvey, Charles Kuralt, and Andy Rooney.

INTERCONNECTED EPISODES

|

The Surprising Life Story of Paul Harvey Pearl Harbor, Pilot, Chicago and Coca-Cola; The World’s Most Prolific Radio Man |

|

How a Tennessee Student Overturned the Scopes Trial Verdict Can you believe the 1925 Scopes Trial was undermined by a Tennessee high school senior? |

|

How the Post Office Grew America? You’ve never heard how important it was for the Post Office to Expand |

|

How the Hostess Twinkie Survived Death Twice Did you know the toaster was invented before sliced bread? And Twinkies almost didn’t survive the 80s. |

|

How Negro League Baseball Solved the Cuban Missile Crisis It was bittersweet to see the Negro League end. So many goods, so many bads. |

|

The Cropduster, The Military Plot and Lindbergh’s 322 bones The world of Lindbergh is wrapped up into so many things. |

SEE THE BIBLIOGRAPHY

SUBSCRIBE AND LISTEN (FOR FREE!)

RATINGS & REVIEWS

If you enjoy this podcast, please give it a rating and review.Positive ratings and reviews help bring Tracing The Path to the attention of other history lovers who may not be aware of our show.