187 Years Behind Martin Luther King’s Dream

This episode meticulously traces the historical roots and interconnected influences that culminated in Martin Luther King Jr.’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech. It highlights how seemingly disparate individuals and events, from the 1831 composition of “America” and the abolitionist movement featuring Frederick Douglass, to the philanthropic efforts of the Rockefeller’s historically Black colleges like Morehouse and Spelman, laid critical groundwork.

The narrative emphasizes the impact of figures like W.E.B. Du Bois, whose “The Problem of the Color Line” greatly influenced later activists, and A. Philip Randolph, a pivotal labor and civil rights leader who first envisioned a March on Washington. Ultimately, the piece reveals how these diverse contributions, including Thomas Dorsey’s gospel music and Mahalia Jackson’s powerful voice, converged to shape the Civil Rights Movement and inspire the profound words that echoed from the Lincoln Memorial in 1963.

Audio Hour:

If you run an activity group, classroom or “audio book club”, click here for more information on using Tracing The Path.

Throughout the episodes, every tune is somehow related to the topic. In the Twinkies episode, for instance, the discussion of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops Baseball team concludes with “Take Me Out To the Ballgame”.

How many do you recognize? And harder, how many can you name?

Most everyone has heard Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech. But most don’t know the people places and events that inspired the words of his eloquent and powerful address.

Welcome to Tracing the Path

America Save The Queen

The tune to the song “America” has no name. It’s the tune of England’s national anthem, God Save the Queen, and is used by 40 other countries in some patriotic way. In 1831, it found life in the United States.

Lowell Mason, a famed organist and composer, had discovered the lucrative business of selling sheet music, working with him on creating books of new music for schools and churches to play was Samuel Francis Smith.

One day, Lowell brought him a pile of music he’d collected in Europe and asked Samuel to go through it and find tunes they could pen new lyrics to. Obviously, this was prior to any copyright or public domain issues that would occur today.

Samuel found the tune which it is believed he had not heard before and wrote out new lyrics that began:

“My country tis of thee

sweet land of liberty

of thee I sing.”

Lowell thought schoolchildren would love this patriotic song, and debuted it at a 4th of July children’s celebration in Boston in 1831. The song was well received and grew in popularity very quickly. The song’s lyrics didn’t resonate with everyone, however. Samuel Francis Smith’s America wasn’t everyone’s America in 1832.

But by 1841 the entire country had heard the song one way or another.

Abolitionists Take the Stage

1841 was also the year abolitionist Frederick Douglass gave his first recorded speech at an anti-slavery meeting in Hingham, Massachusetts. The Hingham Group was just one of 1,350 anti-slavery chapters nationwide. Over 250,000 people were part of the anti-slavery movement, including notables such as Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and poet John Greenleaf Whittier.

The group circulated newsletters had meetings and held rallies. The Hingham Group published a monthly paper called “The Liberator” and sold a book of anti-slavery music, including their own rendition of America:

“My country tis of thee

strong hold of slavery

of thee I sing.”

Harvey Buel-Spelman had been active in anti-slavery groups of Massachusetts before relocating to Ohio, where he became part of the Underground Railroad and part of the anti-slavery movement there. He and his wife were also strong members of the church, which is how they raised their daughter, Laura.

Having seen her mother work hard at the church and in the movement, Laura Spelman decided to go to Folsom Mercantile College in Cleveland to further her accounting skills. It is there she met her future husband, fellow accounting student, John D. Rockefeller.

John was getting his accounting degree to move up at the produce firm where he had started as a teenager. After getting his degree and returning, John’s job involved calculating transportation costs and negotiating prices and collecting debts.

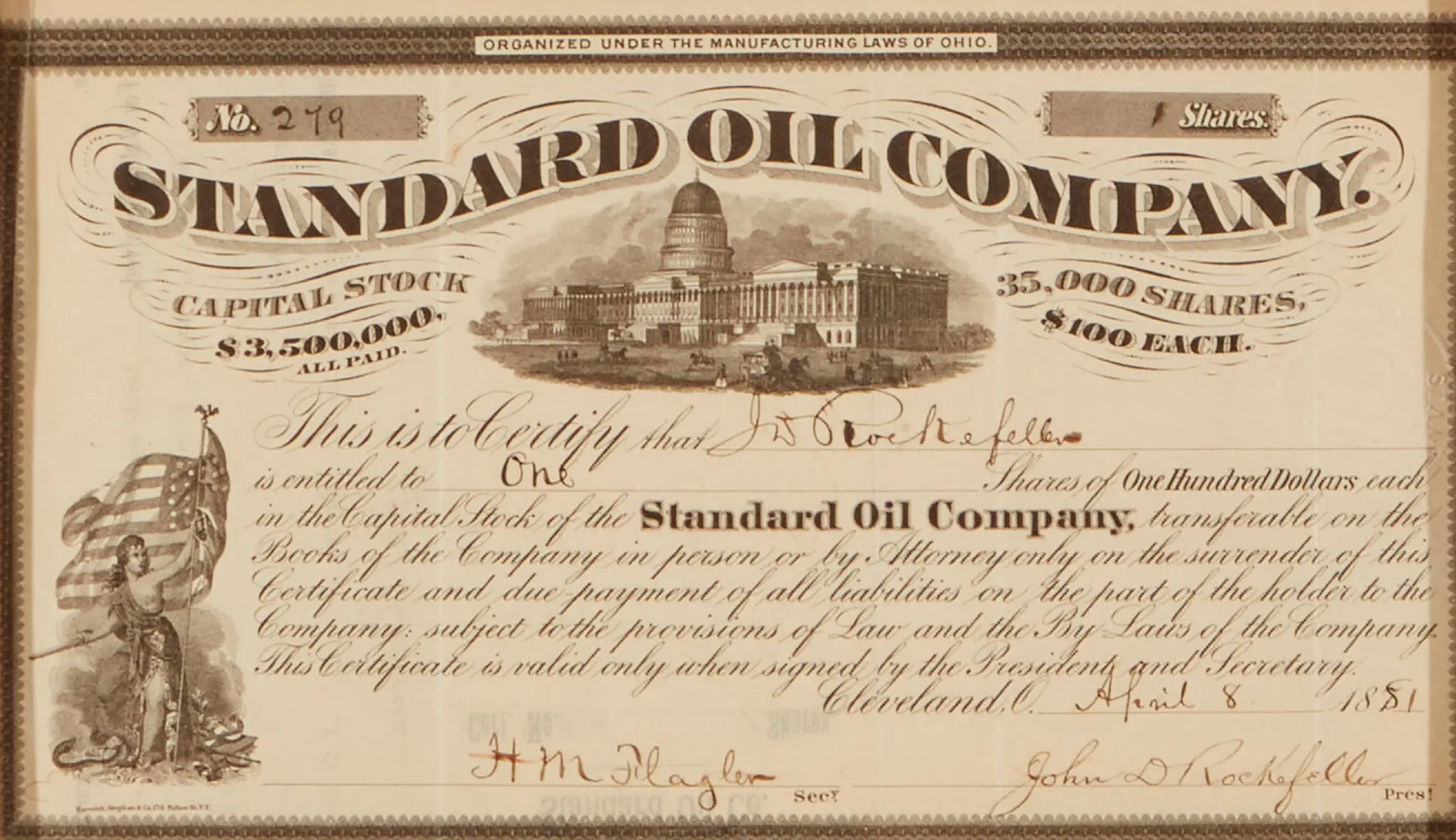

When the Civil War broke out, together John and Laura started their own business, getting the US government the food and supplies they would need for the war, which led them to getting into the oil business and thus a new company called Standard Oil.

The Rockerfellers

Laura and John remained committed to their faith and both to their abolitionist movement. A preacher once encouraged John to make as much money as possible, so he could give it all away to the things he was most passionate about. To that end, John D. Rockefeller and Laura Spelman both worked very hard.

Because of their faith and views of America, they both voted for Lincoln in the 1860 election. Lincoln didn’t agree with slavery on ethical or moral grounds either. In the Lincoln-Douglas Debates leading up to the election, he made his position clear,

“Point to the most important words in the Declaration. We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal.”

And then he asked,

“If there is a man who says these words, do not mean the Negro, why not? If the Declaration is not the truth, let us get the statute book and tear it out. If it is true, then we must stand firmly by it.”

After the election, his position on slavery would strengthen as the Civil War began to tear the country apart, and so after the victory at Antietam, Lincoln declared that all enslaved people in the rebellious states were to be set free. This Emancipation Proclamation would go into effect on January 1st, 1863.

But America didn’t change overnight.

While the Proclamation seemed like the promise African Americans had waited generations to receive, it would become more of a starting point in a new uphill battle.

By itself, the Proclamation merely outlawed slavery in the Confederate States, and it encouraged former slaves to join the Union military and help in the fight. It would take another two years in 1865 before a constitutional amendment would pass a abolishing slavery in every state. But even its language was a promise unfulfilled. It gave slaveholders a loophole to keep up their activities.

The Rockefeller Standard Oil had profited very well from the Civil War, thus they had already began investing their money in projects that helped provide opportunities to African Americans, as well as areas that would expand the Baptist Church.

By 1890, they had given millions of dollars to 34 different schools. One of those was the Atlanta Baptist Female Seminary. The Rockefeller’s had paid off all the outstanding debt and finance construction of a larger building and exchanged for renaming it, Spelman College, after Laura’s family.

And then on a nearby land, they bought and created an all-male college, they named it Morehouse. Both Spelman and Morehouse have since produced many famous alumni. Spelman graduated Alice Walker, author of A Color Purple. And Morehouse has seen actors Spike Lee, Samuel L. Jackson and musician Thomas Dorsey. And activist, Martin Luther King Jr. would walk through its doors.

While their intentions may have been good in their own minds, some didn’t take kindly to white Americans financing institutions for black Americans. One of those was poet W.E.B. Du Bois.

The Great DuBois

W.E.B. Du Bois was born William Edward Burkhardt Du Bois, in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, in 1865. His family lived in a very small, free black population and had owned land for quite some time. William’s great grandfather had served in the Revolutionary War where he was given his freedom, and his grandfather on the other side had been a slave owner who had fathered several children with the slave women. One of those, mixed-race children, was his father.

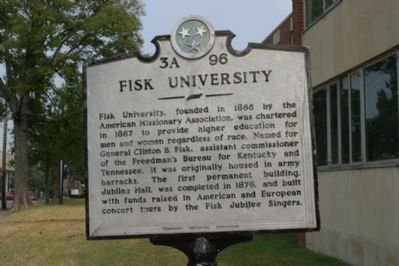

In 1867 his parents married, but two years later, just after his birth, his father left, and his mother died, leaving William to be raised by friends, neighbors, and the church. He shined through the darkness, though, and grew up excelling in school, graduating from both Fisk University in Nashville and Harvard.

Fisk was his first experience with deep-rooted Southern racism. There he developed a feeling of being viewed as subhuman. After Harvard, he received a fellowship to study at the University of Berlin, where he experienced the exact opposite. It was Germany where he developed his clearest ideas of America. He said,

Fisk University Marker.

“I found myself on the outside of the American world looking in. And here they did not pause to regard me as a curiosity or something subhuman. I was just a man.”

Upon returning to America he worked in Philadelphia and could see from his European experience that the key to a good society was not segregation, but complete integration. He said the blacks of the South needed the right to vote, the right to education, the right to be treated equally, the right to decent housing.

In 1903 he published his thoughts in a book called “The Souls of Black Folk” under his pen name, W.E.B. DuBois which famously concluded: “The Problem of the 20th Century is the Problem of the Color Line.”

It was The Souls of Black Folk that convinced a young A. Philip Randolph that social equality was the most important thing to fight for. At the time, A. Philip Randolph was attempting to become an actor in New York City, but really was a transplant from Florida. Florida didn’t have the opportunities he was looking for, however.

A. Philip Randolph

While acting, he and a friend opened an employment office in Harlem to provide job training for Southern migrants. That led him to getting involved with organizing elevator operators into a union. And being one of the few people with any experience putting together a union, he was elected president of the National Brotherhood Workers of America, and then president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first union for employees of the Pullman Corporation.

The Pullman Corporation was the largest employer of African Americans. As the railroads had expanded drastically in the early 20th century, the railroads offered relatively good employment, but in poor working conditions. Philip was able to enroll 51% of the porters, and after successfully lobbying the government for changes, the Railway Labor Act of 1934 was passed. And from that, he negotiated a $2 million pay raise for the poorest. From his work, A. Philip Randolph emerged as one of the most visible spokespeople for African-American civil rights.

The rising conflict in Europe helped end the Depression during the 1930s in America. The booming defense industry created new jobs for whites, leaving black workers disenfranchised again. A. Philip Randolph and friend, Bayard Rustin, proposed a march on Washington to protest racial discrimination in the war industries and desegregation of the military.

Chapters started to organize and Philip sent word to the President that they had mobilized over 50,000 people to march just as the US was entering the war. On June 25th, 1941, Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, which prohibited discrimination in the defense industry. It also set up the Fair Employment Practices Commission to promote equal opportunity in the US.

And so the march was called off.

But the order did nothing to end segregation in the military. So a few years later in 1947, Philip threatened a march on Washington again, spurring this time President Truman to issue executive order 9981, abolishing discrimination in the armed forces.

That brings us to the second third hero of our story. Samuel Francis Smith, John and Laura Rockefeller, Abraham Lincoln, W.E.B. Du Bois, an A. Philip Randolph, are all critical parts of the story.

Now we make our way to the moment all these pieces come together.

Gospel Music Ties

We start back in 1899 with Thomas Dorsey. Thomas grew up in rural Georgia in a very religious household, where music was the forefront. Thomas’ dad was a gospel musician who incidentally was one of the first graduates of Morehouse College. But Thomas gained most of his musical experience, playing the blues at Speak-easys in juke joints.

Looking for bigger and better opportunities, he headed to Chicago, where the jazz and blues were really heating up. At first he found a home composing and arranging jazz tunes and gained a bit of fame accompanying blues’ legend Ma Rainey.

But the gospel music of the South was tugging on his heartstrings.

In 1928, he had a home run with his blues song, “Tight Like That”, selling more than seven million albums. His success with the blues, all but put Gospel music in the background. That is, until the 1930 National Baptist Convention.

Their gospel singer, William A. Ford, sang Dorsey’s song, “If You See My Saviour,” during a morning session, and then was asked to sing it two more times, resulting in Thomas Dorsey selling 4,000 print copies of his song.

Inspired by the moment, Dorsey formed a gospel choir at a church in Chicago. Their rousing renditions had the pastor marching up and down the aisles, Dorsey standing at the piano playing and the congregation dancing between the pews. When the pastor of Pilgrim Baptist saw what the music was doing to the congregation, he hired Dorsey, as his musical director, allowing him to dedicate all his time to gospel music.

Just as his rousing gospel style started to catch on, his wife and first born son would pass away during childbirth. And in his grief, he wrote his now most famous composition, “Take my hand, precious Lord.”

Across the street, from Pilgrim Baptist was a beauty salon run by a young businesswoman who was looking to make a career for herself as a gospel singer. The salon became a social hub for the neighborhood. And incidentally, A. Philip Randolph had organized a chapter of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Carporters at Pilgrim Church as well because of this social hub.

The owner of the salon, Mahalia, had an amazing voice which Dorsey loved. He would often call and have her sing and demonstrate his songs on sales calls. As her local fame grew, he proposed a series of performances to showcase her voice and his music. From that, Mahalia Jackson would start to gain worldwide fame.

One of their performances was at the Golden Gate Ballroom in Harlem, where a representative from Apollo Records heard her and signed her to a full record deal. Her song “Move on Up a Little Higher” would reach a number two spot on the Billboard charts just four years later.

Mahalia’s rising fame would take her to Carnegie Hall, Royal Albert Hall, singing for U.S. presidents, her own CBS Radio Show, and on Ed Sullivan. When she played Orchestra Hall, she was introduced by her favorite poet, Langston Hughes.

Langston Hughes was not only a famous poet, but his poem Harlem had inspired Lorraine Hansberry to write the play “Raisin in the Sun” which also became the first award-winning play by an African-American playwright on Broadway. And the play put one of Mahalia’s songs “We Shall Overcome” front and center.

In 1956 Mahalia sang at the National Baptist Convention, and that is where she met, Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

They became fast friends, and Mahalia was on board to help him achieve his dreams in the Civil Rights Movement.

She even traveled to Montgomery, Alabama, to sing in support of the famous Montgomery bus boycott. And this is where the pieces of the puzzle began to come together.

The 1955 Montgomery bus boycott was the living breathing thing W.E.B. Du Bois was talking about. When he said the trouble of the 20th century would be the color line. In fact, when Du Bois’ book, The Souls of Black Folk, was reprinted in 1961, Saunders Redding, the first African-American professor at an Ivy League school, wrote the introduction, and in it he said, “The boycott of the buses in Montgomery had many routes, but none were more important than this little book of essays.”

The bus boycott was close to Mahalia’s heart. When she had performed in the South, she knew they’d be sleeping in their cars as it wasn’t easy to find hotels that allowed African Americans. In Montgomery, African Americans weren’t even allowed to sit near white people.

So in 1955, when a series of people were arrested for not giving up their seats for whites, the NAACP and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Carporters decided it was time to act. They thought it was time for a bus boycott and decided to create an organization to head the effort.

Martin Luther King Jr. was chosen to lead the movement.

Of those arrested, they felt Rosa Parks would elicit the most sympathy, and thus her trial date was chosen as the boycott start date. The boycott was to be just for one day, with the goal of getting the attention of the city of Montgomery, with the hope of achieving a more respectful situation in the public bussing system.

Everyone, the leaders of the city and the community were surprised by the level of participation they had achieved that day. Almost no one took the bus. That night, Martin Luther King held a rally, asking for the boycott to continue, with the attendees enthusiastically agreeing.

The community came together and created a carpool of more than 800 cars. As the protest went on, word went out within the civil rights community that money would be needed to keep it going. Not only were bicycles needed, but many of the carpool participants needed gas and repair money.

Harry Belafonte, Mahalia Jackson, and Aretha Franklin, among others, all put on performances to raise money. Jackie Robinson invited Jazz artists to put on concerts at his home. Langston Hughes wrote the poem “Brotherly Love,” in honor of the boycott and to bring attention to it. Martin Luther King was already a fan of Hughes. In fact earlier that year, he’d recited his poem “Mother to Son” to his wife for her first Mother’s Day.

While it started on December 5th, the boycott was still going on the following August. Martin Luther King would give a speech the day after the Democratic National Convention, where he called on African-Americans everywhere to use peaceful protests and boycotts to advance their cause.

And in it, he paid subtle homage to Langston Hughes by ending his speech with a rewrite of his poem “I Dream a World.”

A world I dream were black or white

whatever race you be

will share the bounties of the earth

and every man is free.

A little precursor to a bigger speech that was coming.

Then 382 days after it began, the Supreme Court would rule on their case. They ruled it was unconstitutional to have segregate public buses. On December 20, 1956, the Civil Rights Movement progressed one more step, and the citizens of Montgomery began using the buses again.

Martin Luther King would now be flanked by a close-knit group of loyal advisors, A. Philip Randolph, Byard Rustin, Ralph Abernathy, Harry Belafonte, Rosa Parks, Coretta Scott King, Stanley Levinson, Clarence Jones, and Mahalia Jackson.

With the Supreme Court decision under their belt, the movement decided Martin needed to be seen on a world stage. So they sent him to the independent ceremony in the country of Ghana.

They had seen parallels between what Ghana had achieved gaining independence from European colonialism and the struggle against racism in the U.S. Martin would find out later that W.E.B. Du Bois planned to attend, but the U.S. government put a hold on his passport, preventing it.

That night in Ghana, at the independent celebration, Martin Luther King witnessed the lowering of the British Union Jack flag and the raising of the Ghana Flag. He was overtaken with joy and tears, seeing half a million people, elated, singing an old spiritual, “free at last, free at last. Thank God Almighty we are free at last.”

The bus boycott did more than just move the cause of civil rights forward legally. It inspired people everywhere to join the movement.

Prathia Hall was a student at Temple University in Philadelphia at the time. Her first experience with racial segregation happened when she was five. Taking a train to visit her grandparents in Virginia, she was forced to move to a segregated rail car after passing the Mason Dixon line.

Her and her friends at Temple wanted to do their part in the movement, so they participated in a sit-in at a Maryland restaurant that excluded black customers. And, for their efforts, they sat in jail for two weeks because of it.

After she graduated in 1962, Prathia joined the SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and became the first woman field organizer down in Torelle County in southwestern Georgia. She was an extremely passionate and brave woman, being a civil rights activist down there.

There weren’t many more dangerous locations in that.

In fact, on September 6, 1962, White Segregationist Night Riders shot up the house she and other organizers were staying in, injuring all three of them. And then three days later, the Ku Klux Klan burnt down two Baptist churches. Prathia was there in Sasser, Georgia, watching the Mount Olive Baptist Church burn down without a single firefighter responding.

When Martin Luther King learned of the burnings, he immediately went to Sasser to be part of the prayer vigil. The prayer vigil was held on the still smoking ground the next day. That is when Prathia Hall, the leader of the SNCC, led the group in prayer.

She was no stranger to prayer, as her father had found the Mount Sharon Baptist Church in Philadelphia in 1938. Drawing on her Baptist roots, she led the group in an impassioned prayer, repeating the phrase, “I have a dream throughout.”

So moved by her words afterward, Martin Luther King asked Prathia if he could use, “I have a dream” in his speeches.

Moments like these, and the chanting of the crowds in Ghana, would never leave his thoughts.

Ghana Independence Celebration

A couple years later, on April 16, 1963, Martin Luther King was jailed, along with other protesters, for standing up to a new anti-protest law in Birmingham, Alabama. Clarence Jones, his attorney and speechwriter, was the only person allowed to visit him.

On his first visit, he smuggled in a newspaper, so Martin could read the letter eight local white clergymen had printed in the paper. For two days in solitary confinement, without books, without the internet, or help from outsiders, Martin penned a response.

The response was titled “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.”

In its 7,000 words, Martin quoted the Bible, T.S. Eliot, Martin Buber, Abraham Lincoln, Jefferson, Socrates, St. Augustine, and St. Thomas Aquinas, in his own words, all from memory.

That letter was read around the world, including the kitchen table of Jackie Robinson, where he read it to the family.

All the while while Martin was writing Clarence Jones and Harry Belafonte who were setting out to find bail money for all that were arrested. Harry had an idea.

John D. Rockefeller and his wife, Laura Spelman, had long since passed on. But their kids and grandkids held the same religious and abolitionist views of their parents. Their grandson, Nelson Rockefeller, had become the governor of New York, and he had already posed with Martin Luther King once and seemed eager to help.

When Belafonte called, Nelson Rockefeller said, “Meet me at the bank in the morning.” Clarence Jones heeded the call, only to be led into a closed bank into an unlocked vault, where Nelson Rockefeller counted out and handed him $100,000 in cash to necessitate the bales.

Upon his release, A. Philip Randolph felt the time was right. It was the time to do something on a national stage. It was time to renew the idea of the march on Washington.

And Martin agreed.

As such, A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and lawyer Clarence Jones, were put in charge of a march on to Washington. Harry Belafonte agreed to help with fundraising, as well as bringing celebrities to endorse the event.

Bayard created the manual to organize the event, and disseminated 2,000 copies to civil rights groups, labor unions, the NAACP and churches. The manuals called it the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. It was to be held on August 28, 1963, on the Mall in Washington, DC. And the goals mirrored W.E.B. De Bois’s book, Equal housing, Equal rights,voting rights, and an end to police brutality.

Harry Belafonte got 51 chartered buses donated and got hundreds to give money. He also solicited attendance and help from celebrities, like Sidney Poitier and Ruby Dee who were currently starring in “A Raisin in the Sun” on Broadway. Lena Horne, Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Paul Newman, James Garner, Marlon Brando, Charlton Heston, Bert Lancaster, and Judy Garland, among others.

Clarence Jones wrote the speech by taking pieces and parts of other speeches, plus including things asked for by other civil rights leaders and activists. And the government worried about violence, riots, and a loss of control helped by installing a PA system that would reach everyone on the mall.

And without internet or email, their dreams came true.

Over 250,000 people descended upon Washington DC that day to hear a variety of speakers and musical acts in the country’s largest non-violent mandate for change. The schedule was difficult to put together, but in the end, everyone who needed to get a chance to speak got that chance. With Martin scheduled to close out the day.

The only change they needed to make was an announcement. The famed author of the Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. DuBois, had passed away the day before in Ghana. He’d finally gotten there and witnessed their independence.

To build separation from the other speakers and grow the excitement, the organizing team put Mahalia Jackson on stage just before Martin, singing an old Negro spiritual that touched the crowd like no other could. Martin had chosen the song. As Mahalia had become a close personal friend, he was she, he called on, when he was the most stressed, and she would sing him a calming song.

To make sure the crowd fully understood the significance of the moment, Clarence Jones’s final version of the speech started: “Five score years ago”, a reference to Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

But more importantly, to point out, they were standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial in 1963, exactly 100 years after the Emancipation Proclamation had been signed.

Clarence Jones was in awe to hear Martin reciting his exact words. In the hustle and bustle of the big event, it appeared Martin didn’t have time to put his personal finishing touches on the speech.

Mahalia Jackson must have noticed as well, as the language and rhythm were not quite usual. So about halfway through the speech seated behind him a few yards on the steps of Lincoln Memorial she yelled out to him. “Martin, tell them about the dream.”

And Martin Luther King Jr. heard her, as did Ted Kennedy, Clarence Jones, and everyone else sitting in vicinity. Clarence Jones saw Martin gather the pages of his speech, settle his shoulders, and move the paper to the side of the podium.

And then he remarked to the person sitting next to him, “Lordie, America is about to go to church.”

And that’s when it began.

As if he were still isolated in that Birmingham jail cell, without notes, without research. Martin Luther King Jr. reached the very heart of everyone who had sacrificed to be there.

He spoke the words, “Every slave toiling in the field escaped to in their dreams.”

The words every African American on Montgomery was thinking when they just wanted to sit down on a public bus.

The words every mother in the crowd whispered when they had held their baby for the first time. The words every abolitionist prayed for when they voted for Abraham Lincoln.

The words Mahalia Jackson wished every time she had to sleep in her car.

The words of Prathia Hall standing on the smoldering ashes of Mount Olive Baptist Church.

They were the words Langston Hughes encapsulated when he wrote, “I dream a world.”

And he began, “I still have a dream.”

And then standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial, he uttered the argument Lincoln gave in the debates 105 years earlier.

“I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed. We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal.”

An echoing the sentiments of W.E.B. Du Bois, he made it clear that the goal was complete integration and equality. When he said,

“With this faith, we will be able to transform the jangling discord of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood.”

He went on to reference the song that described a country he had never experienced. The song that was supposed to inspire patriotism, but it always illustrated the colorline gap. And he began,

“And this will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning, my country tis of the sweet land of liberty of the I sing.”

And finally, as if he were still standing in Ghana, watching half a million people rejoice in the independence of their new nation, he uttered their chants, saying,

“That when freedom rings from every village and Hamlet, we will be able to join hands and sing. Free at last. Free at last. Thank God Almighty we are free at last.”

A. Philip Randolph’s dream had become a reality. But like the Emancipation Proclamation, would it be enough or just another step? Like his two previous efforts, the March on Washington would result in new positive legislation, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

But a bombing at a Birmingham church killing four kids just a one month later would prove the fight was not over. Then in the early evening of April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King was killed by those still unhappy with progress.

His final words were to Ben Branch, the musician in charge of the music at that night’s event. He asked that Thomas Dorsey’s song, “Take My Hand, Precious Lord”, written in honor of his wife and child, be played.

Mahalia Jackson then sang it at his funeral.

The civil rights movement is much bigger than this isolated story. This instead is the story of the iceberg. All the moments in people who together gave rise to the momentous moment when Martin Luther King stood in Washington DC and gave thee, “I have a dream, speech.” You’ve been listening to the 29th episode of Tracing the Path with Dan R Morris.

CUTTING ROOM FLOOR

To hear all the stories that hit the cutting room floor, you have to listen to the episode.

ABOUT THE SHOW

Let us tell you the story of the 20th Century, by tracing each event back to the original decisions that shaped it. You’ll quickly find out that everybody and everything is connected. If you thought you understood the 20th Century, you’re in for a treat.

Tracing the Path is inspired by storytellers like Paul Harvey, Charles Kuralt, and Andy Rooney.

INTERCONNECTED EPISODES

|

Evolving Civil War Sutlers into the Bob Hope’s USO Many factors went into the success of the USO. It wasn’t necessarily just big hearted celebrities |

|

484 Year Documentary of Muscle Shoals It wasn’t just the music that made it famous? Can you hear Helen Keller? Or see Henry Ford? |

|

Robert Smalls and the Death of Lincoln If Lincoln was with Robert Smalls, he wouldn’t have been assassinated. |

|

Believe it or Not? A cartoonist saved our national anthem. And not just a cartoonist, an American Military March composer as well. |

|

When 26 Million Teens Waited for the Beatles The phenomenon that occurred when the Beatles were live on the Ed Sullivan show could have been predicted. . . |

|

How Negro League Baseball Solved the Cuban Missile Crisis It was bittersweet to see the Negro League end. So many goods, so many bads. |

SEE THE BIBLIOGRAPHY

SUBSCRIBE AND LISTEN (FOR FREE!)

RATINGS & REVIEWS

If you enjoy this podcast, please give it a rating and review.Positive ratings and reviews help bring Tracing The Path to the attention of other history lovers who may not be aware of our show.